Books of the month: From Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto to Unseen by Selina Mills

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for July in our monthly column

Who in this world hasn’t come across someone labelled a “weasel”? However, after reading the chapter “The Weasel Family” in John Lister-Kaye’s moving tribute to nature – Footprints in the Woods: The Secret Life of Forest and Riverbank (Canongate) – it seems these mustelids get a bad press for being sneaky and sly. According to Lister-Kaye, weasels are ferociously courageous, frequently taking on prey up to 20 times their weight. “Pound for pound the weasel ranks with the fiercest carnivores on Earth,” he writes. Pop goes the cliche.

Another book full of natural wonders is Juhani Karila’s Summer Fishing in Lapland (Pushkin Press, translated by Lola Rogers), which is described as a “literary mash-up”. The novel, which was a big hit in Finland, has a wonderfully zany energy, although the swarm of bugs mentioned put me off a trip to Lapland anytime soon. Karila describes the giant horseflies as “black turds with wings” and details how they snip at your scalp and ladle out the blood. “Horseflies were living Swiss Army knives built by Satan himself,” is how Karila flamboyantly puts it.

The “blaring morass” that is London and the “mythical” Lake District are the settings for James Clarke’s engaging, inventive literary noir novel Sanderson’s Isle (Serpent’s Tail). The novel, full of neat twists and potent writing, is about a television presenter and his friend who get caught up in an “off-grid” 1960s psychedelic hippy cult as they hunt for a missing child.

Finally, Anjum Hasan is one of the finest contemporary Indian fiction writers and her sparkling new novel History’s Angel (Bloomsbury) deals with the life of Muslims in India, told through the tale of Alif, a mild-mannered history teacher in Delhi. Alif’s life goes awry when he has a run-in with a student on a school trip.

Novels by Patrick deWitt, Catherine Chidgey, Emily Perkins and Colson Whitehead, along with Selina Mills’s non-fiction book about being blind and a history of British comedy by David Stubbs are reviewed in full below.

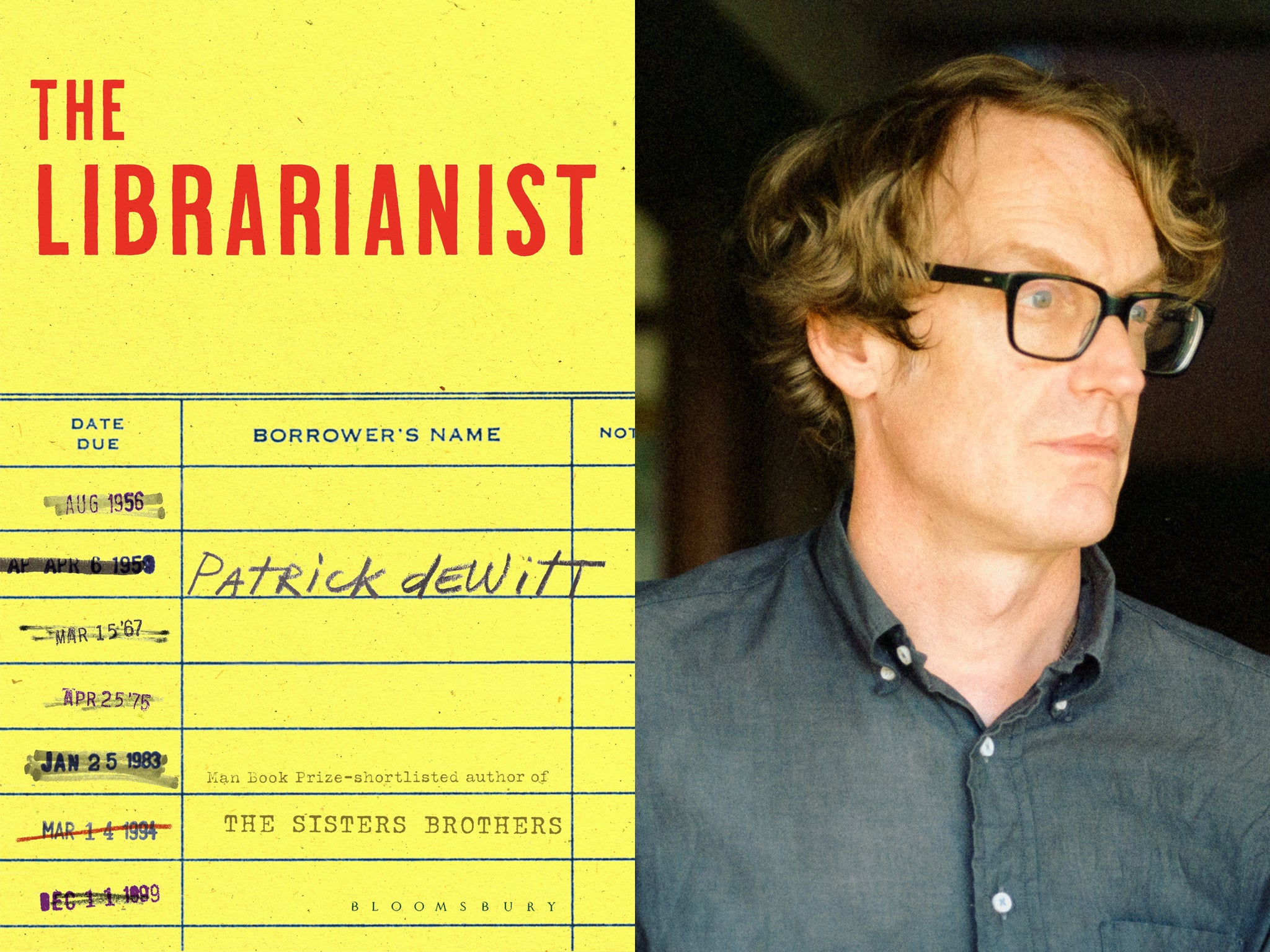

The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt ★★★★☆

“The truth was that people made Bob tired,” says the narrator of The Librarianist, the fifth novel by Patrick deWitt, the Canadian author of the acclaimed The Sisters Brothers.

Bob Comet, the 71-year-old retired librarian who is the protagonist of DeWitt’s excellent novel, has no friends, no family and “a gift for invisibility”. His troubled past is raked up when he decides to volunteer at a care home in his home city of Portland, Oregon (where deWitt lives) and meets someone from his past.

I liked Bob, yet there is no denying that he is something of a berk, a man who misses the emotional truths that are about to slap him in the face with the force of a giant wet towel. His good-natured, irksome personality becomes ever more evident as the author slowly and skilfully reveals the full story of his past and the heartbreaking split from his wife Connie. Throw in betrayal by his supremely confident best friend Ethan and you have quite an emotional cauldron for reclusive Bob to mull over.

The Librarianist, mainly set in 2005 and 2006, is a nuanced account of heartbreak and emotional confusion, and the present is explained by long flashback sections set in the post-war decades. The one that tells the story of Bob and his wife’s meeting (and subsequent rupture) is scintillating. Another, however, about 11-year-old Bob’s picaresque runaway adventure in 1945 – where he meets two jarring old thespian women – just felt strained.

Quibble aside, I would heartily recommend The Librarianist. It is full of subtle reflections on contemporary life and has a deceptively biting humour, as in Bob’s description of lunching with an unpleasant businessman called Mr Baker-Bailey. “It was disturbing to watch him eat because his head was the same colour as the steak,” muses Bob. “He was pushing red meat into his red mouth, and his head was red, and it was like witnessing an animal consuming itself.”

The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt is published by Bloomsbury on 6 July, £18.99

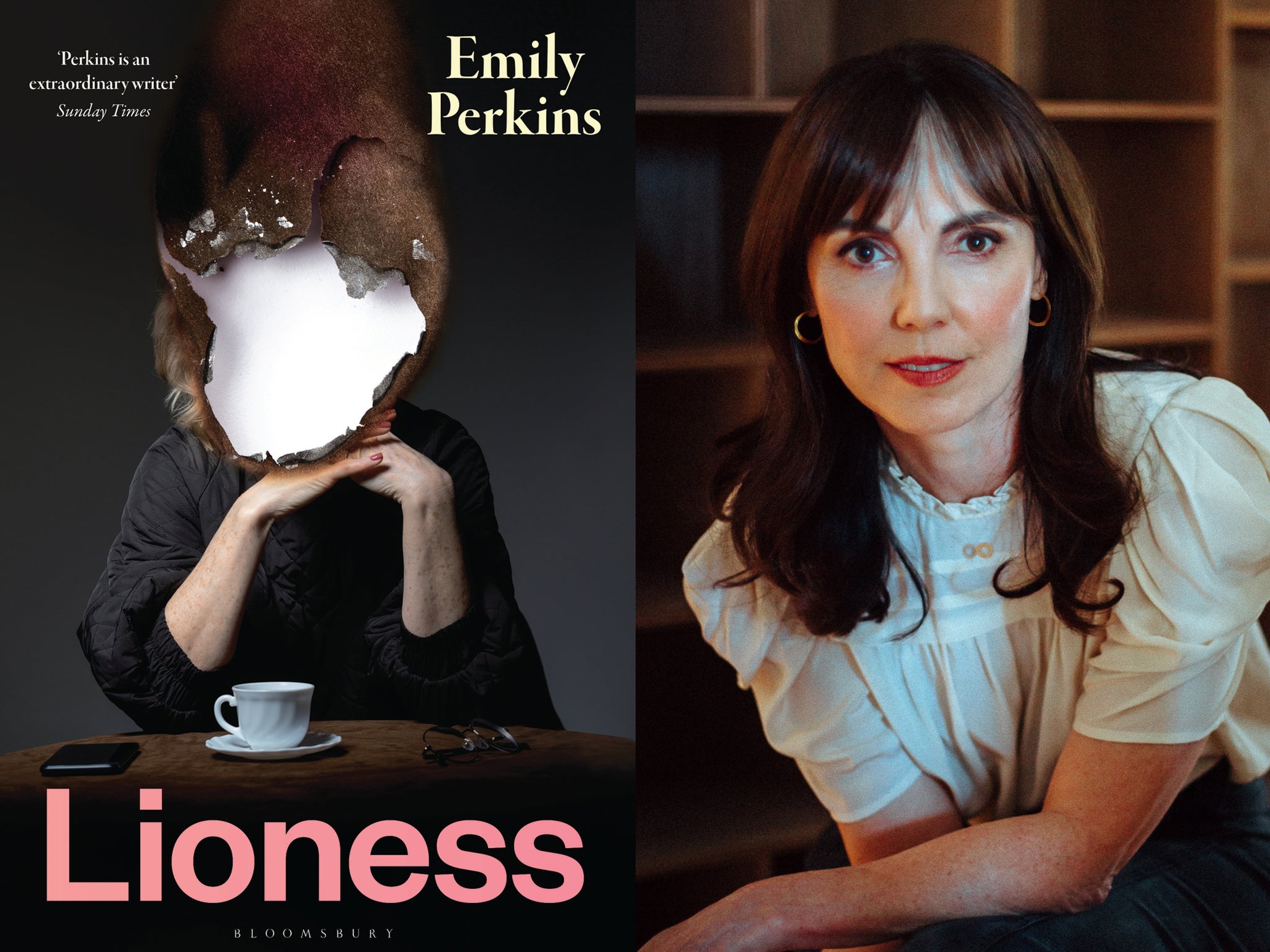

Lioness by Emily Perkins ★★★☆☆

“You look like a deer caught in the headlights of your own life,” Claire tells her neighbour Therese Thorne, a highly successful Kiwi businesswoman. Therese’s life is unravelling because of an impending scandal involving her husband Trevor, whose financial shenanigans have attracted the attention of the Serious Fraud Office.

Emily Perkins’s Lioness, set just pre-pandemic among the privileged of New Zealand, is a well-told story of family rivalry and sibling whining. The portrait of the complaining children of the wealthy is neatly done – Trevor’s son, Heathcote, is described as “a walking battleground between a superiority complex and the inner voice that told him he was worthless” – and the novel explores the damage done to women by living behind a mask.

There are moments of droll humour about the banality of domestic duties: one character complains that if she has to cook pasta with cheese one more time she will “grate her own face”. Perkins, author of The Women’s Prize-longlisted The Forrests, puts real electricity into a scene in which an expectant new-age faith mother and jaundiced parent Claire quarrel over the truth about the agonising pain involved in childbirth.

I wasn’t entirely convinced by the whole Claire-Therese “transformation” dynamic, but the central story is strong, and the growing despair of second-wife Claire – younger than Trevor and just hitting the age when she is discovering what it’s like to be “part of the great formless mass of the middle-aged” – is captured smartly.

Lioness by Emily Perkins is published by Bloomsbury on 6 July, £16.99

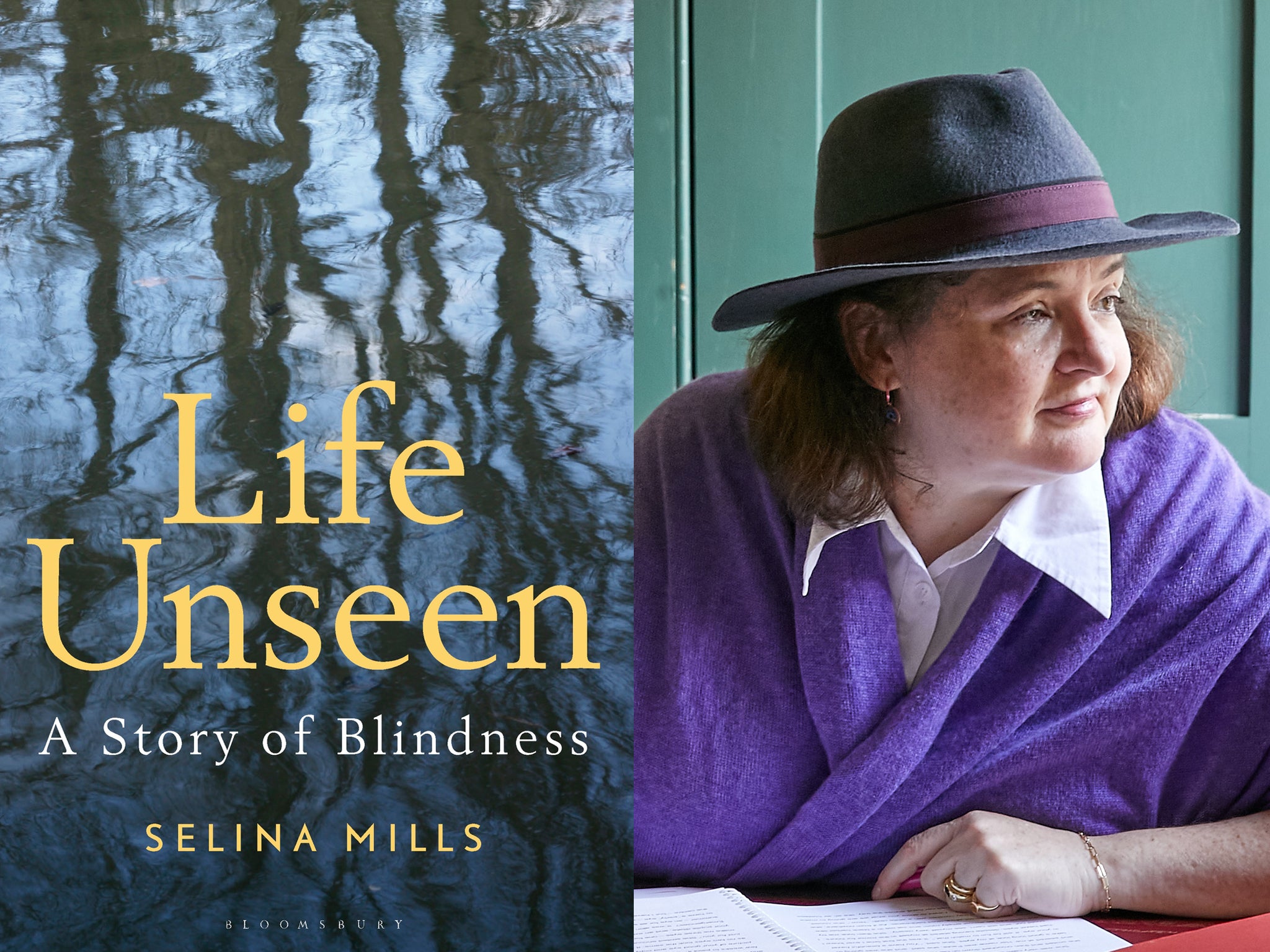

Life Unseen: A Story of Blindness by Selina Mills ★★★★☆

When an obsession with sight-curing took hold in the 18th century, the bogus remedies included squeezing the blood of a pigeon’s kidneys over a blind person’s eyes, or even placing leeches there. This, and much more, can be found in Selina Mills’s informative, heartfelt book Life Unseen: A Story of Blindness.

Mills, a journalist and broadcaster, is among the more than 2 million Brits who are registered blind, or severely sight-impaired. She details some of her own shocking experiences, including how she pierced her eye membrane while working at The Telegraph, and how she was driven to such exasperation by an obdurate railway guard that she pulled out her own false eye to convince him that she was not faking eye problems.

She also reflects wistfully on the behaviour of other people around blindness. When she was filming a news segment about a new app for the blind in 2022, she recalls that the cameraman asked: “Could you act more blind, lovely?” He wanted her to fumble around, looking for the door. “Er, I don’t think blind people behave like that,” Mills told him. “A door is not so hard to find really.”

I was particularly struck by her anecdote about a blind friend with a guide dog. “He says he is constantly shocked by how everyone talks to the guide dog and not the person behind the dog,” Mills recounts.

Mills points out how “ocularcentric” language (we all say “see” to mean understand, and use “look” to emphasise an argument) can be damaging. She also details how blind people are consistently portrayed in terms of polar extremes: inspirational or tragic. Charles Dickens is rightfully upbraided, incidentally, for revelling in the “blind gloom trope”, offering Victorian readers “the myth of the blind inspirational innocent” as redemption narratives.

These mordant reflections aside, the book is mainly a celebration of the lives, stories and achievements of blind people. As Mills takes us through the history of blindness in Western culture, there are nuggets about everything from blindness in Neanderthal times to the realities of being blind in a world of apps, smartphones, Braille, guide dogs and white canes. Her account of what it’s like to choose a Perspex false eye (and the process of pouring blue goo into an eye socket to manufacture the right size) is told with wit and disarming honesty. Mills does not want to be defined by her blindness and this admirable book dispels myths around the condition.

I should also add that Mills warns readers not to google “oculophilia”. I went no further than checking the definition of the term – for eye fetishism – clicking immediately away to avoid graphic details about people who seek a sexual thrill from licking eyes. Jeepers peepers!

Life Unseen: A Story of Blindness by Selina Mills is published by Bloomsbury Academic on 13 July, £20

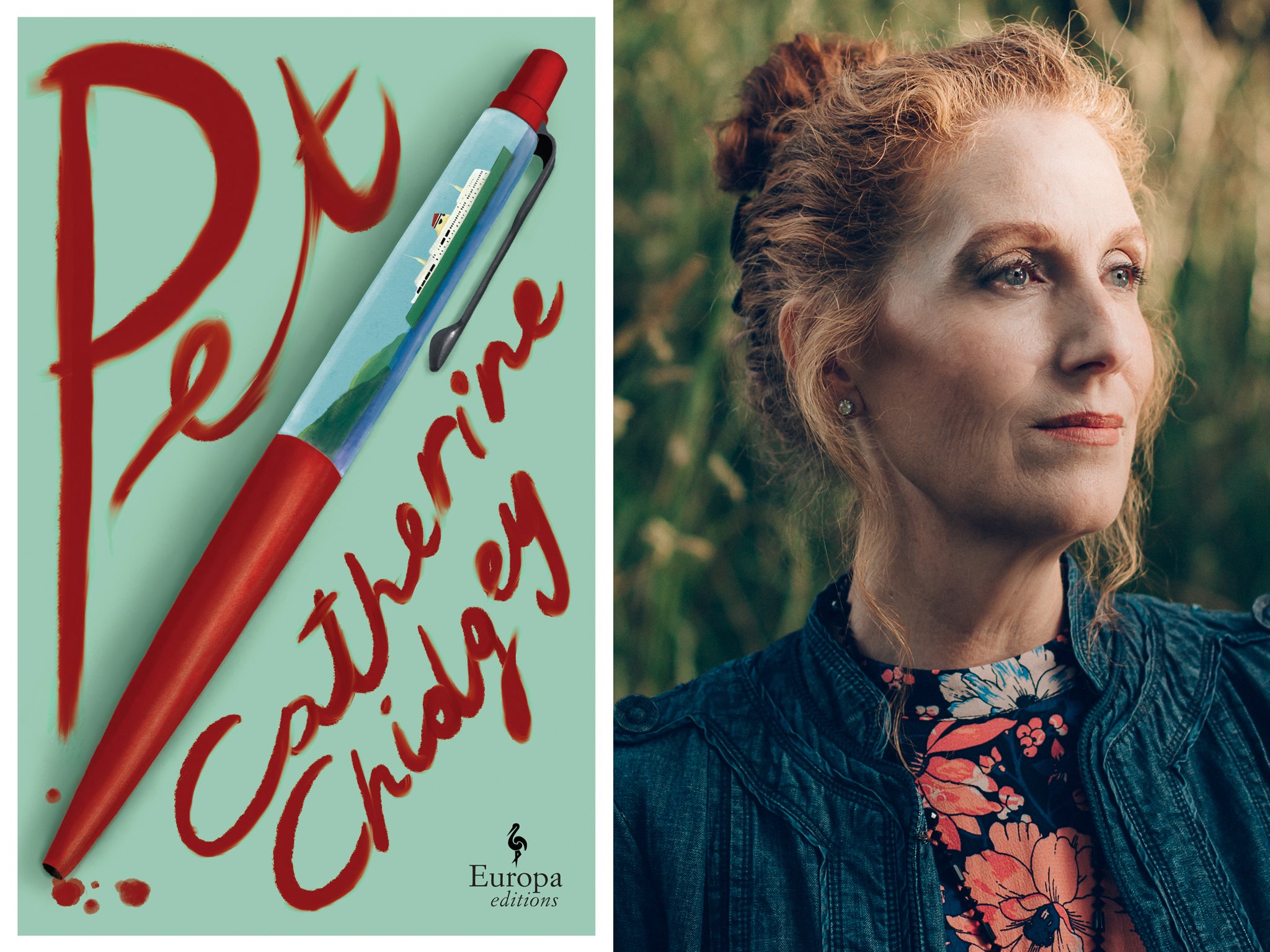

Pet by Catherine Chidgey ★★★☆☆

“I was the favourite of the favourites, the top pet,” says 12-year-old Justine, who has won the class battle to be the prized pupil of a charismatic new teacher called Mrs Price.

Pet, written by New Zealand novelist Catherine Chidgey and set in her homeland in 1984, is a skilfully crafted tale that slowly gets darker and darker, as the full story behind a series of thefts in the classroom is brought to light. The novel explores casual sexism, racism (“a big yellow s***,” says one girl of Justine’s friend Amy Wong), drinking problems, grief, sexual awakening, puberty, jealousy and betrayal.

There are small flashback sections from 2014, but the heart of the action is a coming-of-age 1980s setting, with references to Christie Brinkley, Princess Diana and a dishy boy who looks like “a Maori John Travolta” (Amy and Justine write his name in biro on their thighs). Chidgey, who was born in 1970, gently probes the question of body image insecurity that is a constant of growing up for children anywhere on Earth. There is a caustic account of 1980s body-shaming in the way Justine and her father offer a cruel running commentary on the Miss Universe contest. “Aruba had bulky thighs, Gibraltar was fat, Argentina had wonky teeth and far too much make-up, Honduras’s eyes were too close together”).

Pet is crisply written and full of moments of delight.

Pet by Catherine Chidgey is published by Europa Editions on 13 July, £14.99

Crook Manifesto by Colson Whitehead ★★★★☆

Crook Manifesto, set in the 1970s, is the second part of a trilogy that started with Harlem Shuffle (the action of which took place in the 1960s) and which is due to finish with a novel that unfolds in the 1980s. Colson Whitehead’s entertaining literary crime saga again features furniture salesman and small-time crook Ray Carney, who is trying to keep from being burned in the vast, complicated and shady New York of the late 20th century.

The book is full of the same sharp edges and biting humour that infused Harlem Shuffle – one character in the new book is called Corky, nicknamed because his brother tried to drown him at the age of five in a creek and he “kept floating up” – and the blend of violence, sardonic observation and out-and-out comedy reflects Whitehead’s ability to neatly balance the trick of writing both a homage to, and affectionate tease of, noir crime fiction.

Whitehead, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author, divides his book into three separate interlocking stories. The first, set in 1971 and called “Ringolevio” (named after a children’s game), is certainly the strongest. Carney, back doing shady business, is drawn into the world of a corrupt and brutal cop called Munson. Both police officer and crook live by Harlem rules – rowdy and unpredictable – and Munson is a graphic, repulsive character. His freedom to act unlawfully with impunity allows Whitehead to explore the corruption and venality of 1970s New York law enforcement.

The following sections – featuring political cronyism, racism, arson, and the reappearance of the memorable violent criminal Pepper – are set in 1973 and 1976. They both feel well-researched and are full of tiny telling details but, despite fine moments, they fail to grip in the easy way that “Ringolevio” does.

Overall, Crook Manifesto is another hugely enticing read. And you root for Carney, despite his foibles and partly because of his hard-earned wisdom and his sense of what is grimly funny. Back in 1971, Carney’s children are desperately collecting Jackson 5 balloons from Honey-Comb cereal boxes. The company rationed the Michael Jackson ones, although it was easy to land a Jermaine, Jackie, Tito or Marlon. It takes 14 purchases for Carney’s daughter to find a packet with a balloon imprinted with Michael’s likeness. “Like everything in life, the Jackson 5 promo was rigged. Carney approved: Teach ‘em early,” Whitehead writes.

Crook Manifesto by Colson Whitehead is published by Fleet on 18 July, £20

Different Times: A History of British Comedy by David Stubbs ★★★☆☆

Surely a joke about “Mrs Slocombe’s pussy” will leave almost everyone under 40 bemused and unamused? Mrs Slocombe was a mainstay of Are You Being Served?, one of more than a hundred tired sitcoms that were broadcast in the 1970s on terrestrial television. The humour seems so dated. According to David Stubbs, in his sweeping book Different Times: A History of British Comedy, there was a sense that this hugely popular show “speaks to Britain about Britain, the kind of people we are: sexually repressed, grumpy but not militant, cheeky but not revolutionary”.

The book navigates more than a century of comedy, starting with the trailblazing brilliance of Laurel and Hardy. This section also deals with Charlie Chaplin, although given the latter’s vile history of sexual predation you can see why Stubbs’s mother dismissed the little man with the cane and bowler hat for “giving her the creeps”. Stubbs guides the reader through the evolving comedy landscape of the 1950s, 1970s grotesques such as Benny Hill, the alternative scene of the 1980s, and up to the genius of Stewart Lee, a man the author rightly hails as “unmatched as a comedian in the 21st century”.

Stubbs highlights many of the deep problems with British comedy’s past, especially the bigotry (so much vile racism and so many comedians left with the stain of having performed in blackface), the sexism, the elitism. I would like to have read more than the five paragraphs devoted to a section headed “Goodness Gracious Me and the Stalled Rise of Asian Comedy”. The comedy scene was also blighted by homophobia and the author notes that Richard Ingrams – co-founder of Private Eye, a publication he originally wanted to call The Bladder – allegedly “took a dim view of homosexuals”. Early editions of Private Eye were “rife with references to ‘pooves’,” Stubbs notes.

Yep, different times.

The author is not shy of offering his own strong verdicts on the merits of performers. Although he acknowledges that Spike Milligan was “comedy’s own Picasso”, Stubbs calls him “deadeningly unfunny”, adding, “I sometimes feel that if just one reader is persuaded, after reading this book, not to bother watching Q, this enterprise will have been worthwhile.” Stubbs also believes that Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag “pushed comedy to the brink”. I seriously doubt that, but then perhaps comedy, like football, is just too subjective. One person’s laugh is another’s yawn.

Nevertheless, the book is full of interesting tidbits for comedy aficionados, including the information that repulsive stand-up comedian Bernard Manning, as a young soldier, was responsible for guarding Rudolph Hess. It’s also hard not to see Harry H Corbett, of Steptoe and Son fame, in a different light knowing that he carried with him a past that involved killing two Japanese in New Guinea while on service.

The book is very man-heavy, though Stubbs does tackle the thorny issue of the decades-long sidelining of women in British comedy. He highlights a remark by Carol Cleveland, a regular side performer in Monty Python, who coined the term “glamour stooge” to describe the unsatisfying roles given to women. He also praises the work of Millicent Martin in the 1960s – she later found fame in Frasier as Daphne’s mother Gertrude – and talks about Connie Booth’s legacy as co-creator of Fawlty Towers. “There is a reason why John Cleese never again matched the quality of Fawlty Towers, and that reason is largely Connie Booth,” opines Stubbs.

Different Times is an entertaining read, yet I do have a few brickbats. The content is too slanted to the 1970s – presumably the formative watching years of an author born in 1962 – and it would also have merited a more thorough discussion of the problems of the hugely popular Noughties show Little Britain. And, overall, there is too much emphasis on television. Leaving Jim Davidson out of the book is a small mercy, but where is playwright and screenwriter Joe Orton in this history of British comedy? And among all the discussion of Oxbridge-based comedy, it would also have been good to see a mention of Early Doors, a comedy set in a pub in Stockport, and Joe Gilgun’s inventive 21st-century working-class comedy Brassic.

One of Stubbs’s favourite comedians is the magician Tommy Cooper. “If you’re left cold by Tommy Cooper, there’s something wrong with you. Go to a doctor,” he concludes. In which case, it seems only fair to end the review with a Cooper joke from the book. “I went to the doctor’s and he looked in my mouth and said, ‘a little raw’, so I said, ‘Raagghhhr’.

Different Times: A History of British Comedy by David Stubbs is published by Faber on 27 July, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks