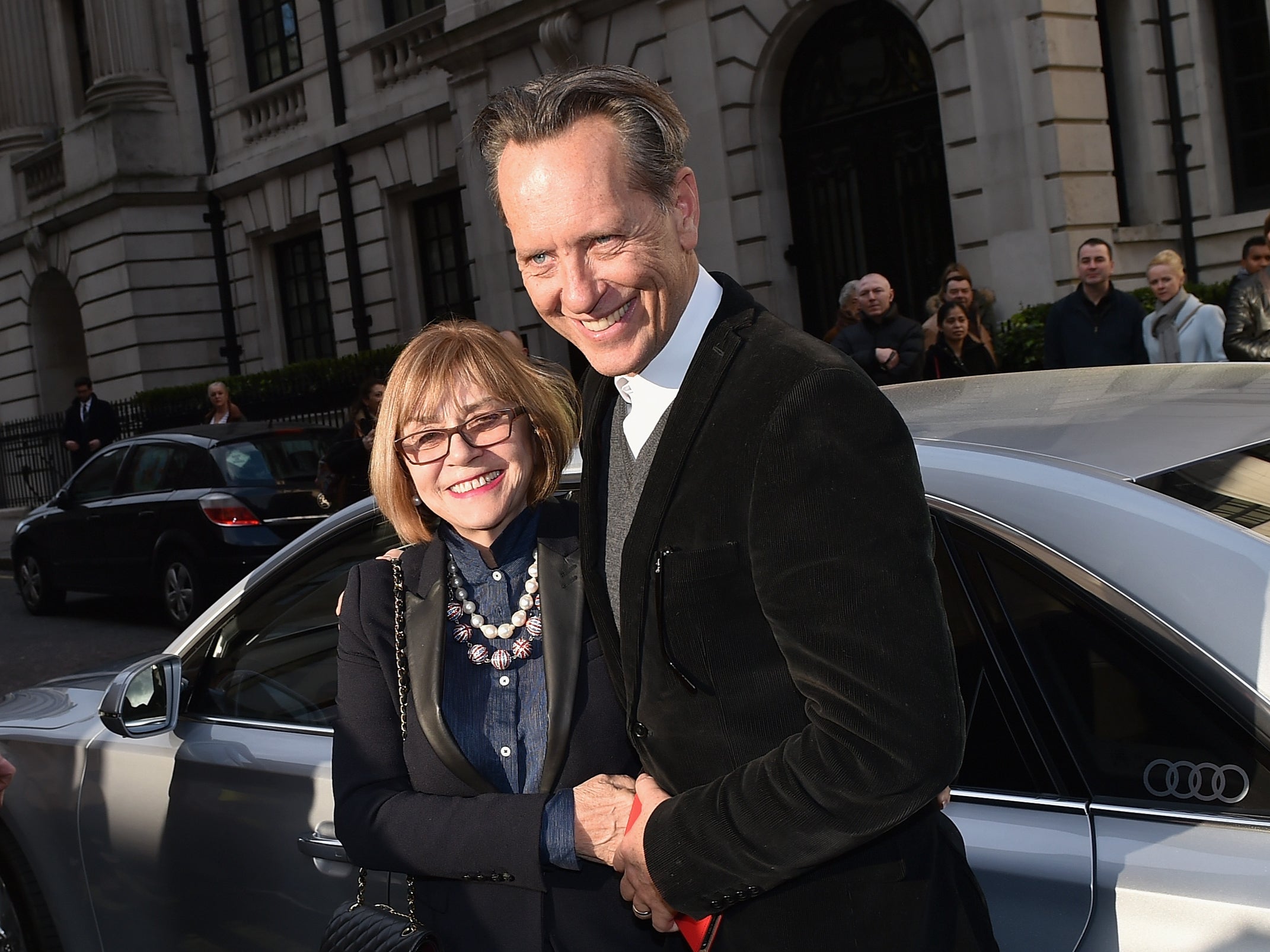

Richard E Grant on grief, music, and his late wife Joan Washington: ‘I still have silent conversations with her’

The ‘Withnail and I’ star has spoken candidly on Instagram about the pain of becoming a widower, and in his moving memoir ‘A Pocketful of Happiness’. He sits down with Laura Barton while touring his one-man show, ‘An Evening with Richard E Grant’

Some while ago, the actor Richard E Grant found a cake tin tucked away in the west London house that, on good days, he might describe as “maximalist”, and on others might concede reveals unbridled hoarding tendencies. “Every inch of our house is rammed with stuff,” he says brightly. “I’ve got stuff everywhere.”

Grant thought the tin might contain some left-over Christmas cake. Instead, inside he found a stash of letters that his wife, the dialect coach Joan Washington, had sent to him throughout their courtship and subsequent 35-year marriage.

Washington died in early September 2021, eight months after a diagnosis of lung cancer. Her letters play an integral role in A Pocketful of Happiness, a memoir in which the events of Grant’s life and career are strung along the central thread of his relationship with Washington. They detail the heady early days of their romance, when she writes of how “the world feels quite beautiful”, quotes John Donne and DH Lawrence, and confesses how many times she has replayed Grant’s message on the answering machine. They bestow nicknames, impart acting advice, and above all, bring her own voice to the story: passionate, open, strong-willed, inquisitive.

To read those letters again, to include them in the memoir, seemed natural and right to Grant. Washington remains a constant presence in his life, her voice still resonant, their long conversation ongoing. “I don’t talk out loud [to her], but after 38 years together I know I can anticipate or predict what her response to whatever’s happening in my day would be,” he says. “So I have a silent conversation with her, especially at the steering wheel at the end of a day, or at the end of a show... cross-reference what she would be thinking.”

Today, Grant is backstage at Warwick Arts Centre, preparing for his one-man show, An Evening with Richard E Grant, in which he walks on stage wearing a replica of the coat he wore in Withnail and I (the original was sold at a charity auction, to the radio DJ Chris Evans), and, drawing frequently on the book, recounts stories from across his 66 years – film sets, famous friends, the love and loss of Washington.

He makes for rum company this afternoon, our conversation ranging from the horror of tea-slurping to the challenges of a Geordie accent and the particular pain of watching terrible theatre productions. He is faintly mischievous, and unwaveringly polite, and, with his long limbs and angular features, looks something like a crane fly folded into an armchair. Later, I will wonder whether I have confused my invertebrates, recalling Washington’s description on the first night they ever shared a bed: “You’re as skinny as a stick-insect!”

The bed features often in Grant’s account of his marriage – there in that first encounter, of course, but reappearing frequently in the pages that follow; he tells me how the couple adhered to the notion that partners must never go to sleep on an argument, and how every time one of them went away they would leave a note under the other’s pillow.

Even as she grew increasingly unwell, Washington remained determined to make it up the stairs to their room each night, and it was only towards the very end of her life that she relocated to a hospital bed, installed in their house in the Cotswolds. “Obviously a hospital bed can be levered up and down,” Grant explains, “and as my bed was directly behind her, she had the exact same view. It looked out over the garden that we made together.”

When they met, it was Washington, 10 years Grant’s senior, who had the high profile. “The National Theatre, Royal Court, Royal Shakespeare Company...” he reels off a list of theatrical companies who had enlisted her services. She had worked with Richard Eyre on the National’s Guys and Dolls, and Barbra Streisand on Yentl. Later she would coach Vanessa Redgrave, Thandiwe Newton and Emma Stone, among many others. In 1982, hiring her to retrain what he describes as his “colonial accent”, Grant couldn’t afford Washington’s £20-an-hour fee, and bargained her down to £12 on condition that he would reimburse her should he ever make it big.

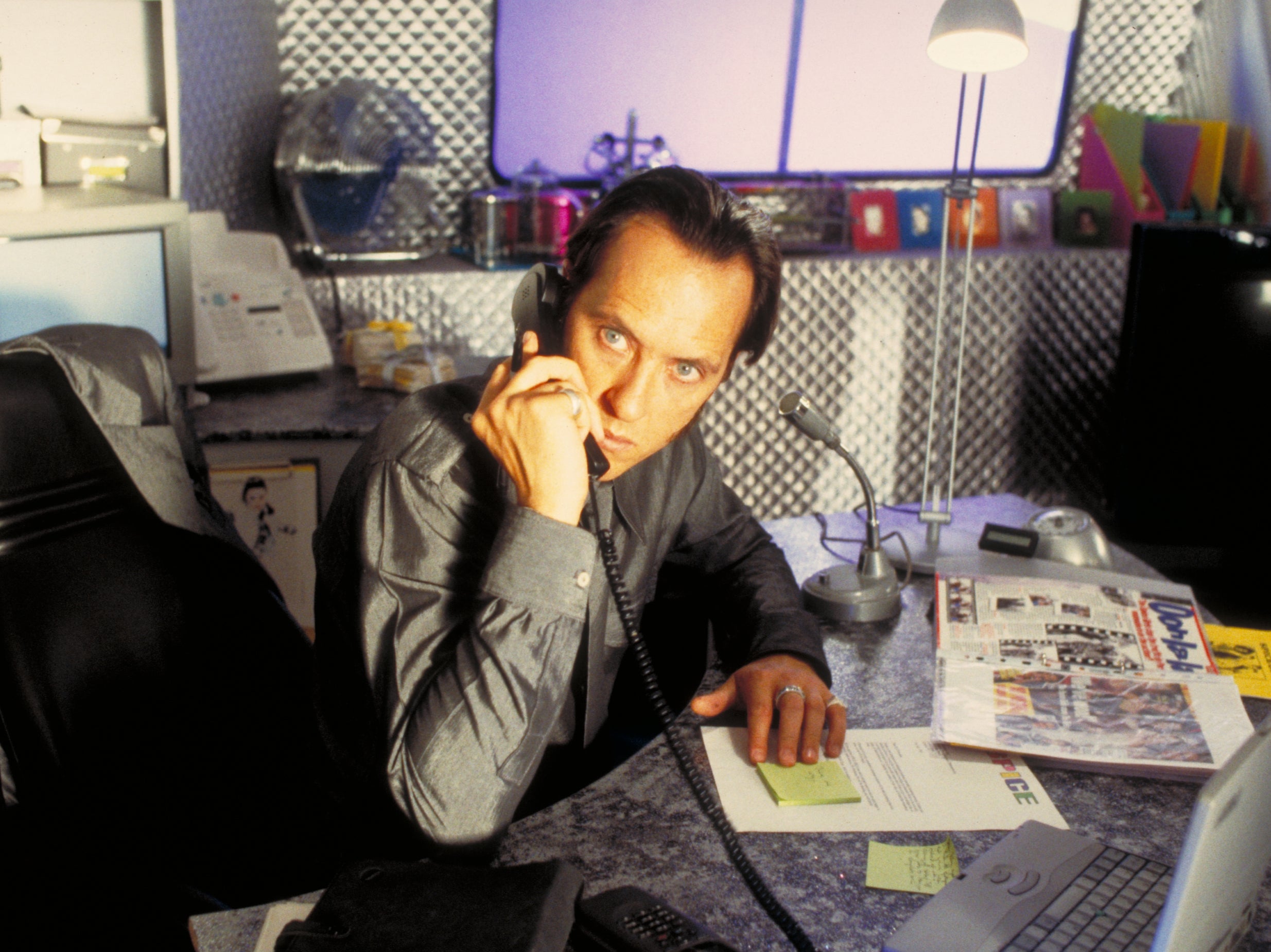

It was another five years before Grant got his break, playing an out-of-work actor in late-Sixties London in the Bruce Robinson written-and-directed Withnail and I. Swiftly regarded as one of the finest British films of all time, it has garnered international cult status and inspired drinking games ever since.

The pair had been married a year when the Withnail premiere took place at the Haymarket cinema in London. Grant was filming overseas, and so Washington went in his stead, wearing “black silk, taffeta and jewels”. Afterwards, she wrote to him: “Kept a low profile, but everyone who clocked that you were my husband said, ‘He’s a star’ and I could only reply, ‘Yes he is!’”

But over the years, as Grant ascended, through How to Get Ahead in Advertising, Henry & June, LA Story, Gosford Park and beyond, Washington struggled with the shift in profile. “The changeover,” as Grant calls it now. “What happened is that as my visibility increased, she found being pushed aside by people very frustrating.”

He has many examples. “We were once at a dinner in LA, and somebody sitting next to her said ‘What do you do?’ and she said ‘I’m a dialect coach.’ And the person literally turned his back and didn’t speak to her again for the rest of the evening.” He looks steely.

Often, Washington, tiny in stature, was physically pushed out of the way by people eager to speak to her more famous husband. The frustration was cumulative. By the time Grant was nominated for an Oscar for his role in 2018’s Can You Ever Forgive Me?, she had reached her limit. She told him she didn’t want to go to the ceremony; that he should take their daughter, Olivia, instead.

Just a month ago, Grant was given a recording of an interview Washington gave to Rose Scarborough, wife of the actor Adrian Scarborough. “Rose was doing a project where she was interviewing the partners of actors about what that was like,” he explains. It offered new insight into the delicate calibration of their marriage, as he heard Washington describe how “she found it very frustrating that when I met her she was the one that was the most well-known in the profession, and then...” He tails off. But it was a beautiful thing to hear her voice, her mind again. “It felt like a real gift.”

Grant hadn’t been aware that his wife had taken part in Scarborough’s project. But this in itself was very Washington. It wasn’t that she kept information from him; rather that she dispensed it on a need-to-know basis. This meant that throughout their long relationship, she still retained the capacity to surprise him, casually dropping into a conversation a previously unbroached event from her life, or the name of someone she’d once slept with.

Sometimes this withholding was protective. It took her many years to tell Grant that in the early days of their relationship, her friends had been wary of him – the handsome out-of-work actor, 10 years her junior. Washington was married, though separated, when they got together. It was quite typical of her, he says, that she told her ex-husband that she was in love with Grant before she even told him.

Today, Grant wears two watches: one, given to him by Washington, is set to Greenwich Mean Time. The other, a replacement for a watch once given to him by his Father, is set to “Swaziland time” – the country of his birth, now known as Eswatini, is two hours ahead.

It’s tempting to regard Grant as somehow moored for ever in the space between these two poles, but what has been remarkable about the memoir, his media interviews, and the frequent video postings he makes to Instagram, is that they have not only articulated his grief, but shown how fiercely he has gripped life. For the past 20 months, he has lived according to the book’s title – an instruction from Washington, that he should try to find “a pocketful of happiness in every day”.

Life, after all, still brings many pleasures. The book, just out in paperback, has taken him on a tour of Australia and New Zealand, along with the UK, and will carry him to the US later this summer. This week, the audiobook incarnation won the Best Non-Fiction prize at the British Book Awards. Like many actors, he is also waiting to hear whether the writers’ strike will put his next filming projects on hold.

In February, he was given the “incredible privilege” of hosting the Baftas – where he aimed to be a “celebratory” host rather than continuing the trend for mocking the acting community. “I’m going to be singing like Billy Crystal, dancing like Fred Astaire, more beautiful than Joanna Lumley,” he promised in advance. On the night, the lustre dimmed only once, when, as he introduced the In Memoriam segment of the evening, Grant briefly broke down. Even on screen, one could feel the swell of compassion from the audience.

But he has noticed that death has a strange effect on other people. For all the generosities of friends – Nigella sending Tuscan bean stew, King (then Prince) Charles bringing a bag of mangos (Washington’s favourite fruit) – there have been those who failed to write, or to call, throughout her illness, or who drifted from their orbit, uncertain what to say.

I have no religious conviction whatsoever, but the fantasy of finding that person that you’ve loved again is what you long for

A month ago, he found himself in the South of France, where a Swedish couple he and Washington had known for over 20 years chose to blank him. “They were two metres in front of me, sitting in a cafe, and she nudged him, and said something, and simultaneously their heads turned left and they averted their gaze,” he says, flinty with disbelief. “God knows, I felt I’d been punished.”

Grant has a fine eye for the details of others, for all of our flaws and foibles. It makes him marvellous company, and a remarkable actor, capable of great subtlety and range: he can capture flickers of humour, gentle eccentricities, the minute thawing of the stony-faced. He can give it blousy and big, as in The Player; he is pained and long-simmering as the Spice Girls’ manager in Spiceworld; and charmingly romantic in Jack and Sarah.

It’s also part of what keeps A Pocketful of Happiness from ever being a saccharine portrait of a marriage. He details Washington’s bluntness, her intense annoyance at the speed at which he ate any meal, and her habit, mid-argument, of going “Henry Higgins on me, with an accent correction”. He never wholly fathomed her dislike of violins and saxophones, “Except Joan loved to read, and she couldn’t read with music playing,” he says. But over nearly four decades, they learned the quiet navigation of a happy marriage, from silence to music and back again.

Washington used to ask Grant whether he had mortally offended someone high up at the BBC – how else to explain his never having appeared on Desert Island Discs? The invitation finally arrived after her passing, and his choices felt charged with her absence. When it came to his selection of Eva Cassidy’s cover of “Fields of Gold”, he broke down. “I have no religious conviction whatsoever, but the fantasy of finding that person that you’ve loved again is what you long for,” he said. “Music is the emotional wallop, or the key to understanding everything in a way that goes beyond language.”

Today, he tells me how he keeps a record of the saddest musical notes he hears, and is struck by how they can affect him. When I ask him what he thinks is the saddest song, he answers without hesitation: “Joni Mitchell, ‘A Case of You’.” He pauses, and for a moment we both think of the track.

Throughout our conversation, as we have discussed loss and sorrow and love, Grant has been poised and collected. But now, as we think of Mitchell’s song, his face seems to catch and to dampen, and his voice falls still. I think of a line from one of Washington’s early letters, written in the throes of new love: “I can’t find the right words to tell you how I feel,” she wrote, “because the sensations are new to me.” Somewhere in his face, I think, lies a sensation that goes beyond language.

‘An Evening with Richard E Grant’ is touring the UK until 31 May. His second memoir, ‘A Pocketful of Happiness’, is out now in paperback, published by Gallery UK

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks