Books of the month: From You Are Here by David Nicholls to James by Percival Everett

A new page-turner from ‘One Day’ author David Nicholls, Andrew O’Hagan’s majestic new state-of-the-nation novel, and Percival Everett’s spin on Mark Twain’s 1884 novel ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ – Martin Chilton picks the best reads for this month

After taking a stroll near Lewes in Sussex in 1932, Virginia Woolf wrote a striking phrase in her diary: “I want to walk, alone, and come to terms with my own head.” The quote appears as the epigraph to Harriet Baker’s Rural Hours: The Country Lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner & Rosamond Lehmann (Allen Lane). It is a delightful read, enhanced by quirky photographs – including several of these visionary writers with their goats.

When Boris Johnson praised the “vaccine success” he attributed it to “greed, my friends”. His quotation is used by Angus Hanton in the chapter “The NHS Cash Cow” in Vassal State: How America Runs Britain (Swift), a depressing read about how US companies have siphoned profits from Britain. Hanton, a public policy expert, details how a £500m pandemic stockpile of PPE, bought from American companies, was poorly maintained and in a shoddy condition. Hanton’s conclusion is that, when it comes to expensive US private providers, “greed did not deliver success for Britain. It cost us dearly.”

Social historian Sarah Wise has written an important, shocking book in The Undesirables: The Law That Locked Away a Generation (Oneworld). It is estimated that 50,000 Britons were incarcerated as “defectives” under the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act. Wise’s “Appendix 2: Anecdotes of Women Detained for Having a Child Out of Wedlock” is one of the bleakest I’ve read for a long time. It includes numerous accounts of women being locked up for decades in asylums and heavily sedated, just for giving birth. Wise throws light on a shameful national scandal.

Two quick fiction recommendations. First, Jo Hamya’s The Hypocrite (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), in which playwright Sophia deals with her novelist father’s shortcomings via a brutal play about a holiday she took with him as a teenager, is caustically funny and includes a sharp line about the overpriced “bad-wedding kind of wine” you get at London theatres. Meanwhile, Catherine Chidgey’s The Axeman’s Carnival (Europa) offers a shrewd look at human foibles through the eyes of a talking magpie called Tama. This novel is an imaginative treat.

Novels by Andrew O’Hagan, Percival Everett, Scarlett Thomas and David Nicholls, along with non-fiction books by John Connell and Carol Atherton, are reviewed in full below.

Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan ★★★★★

“It’s always about complicity,” says investigative journalist Tara, whose “news splashes” help to expose the financial, moral and trafficking scandals at the heart of the downfall of powerful socialites in Andrew O’Hagan’s majestic new state-of-the-nation novel Caledonian Road.

When art historian Campbell Flynn, a celebrity “thinker”, starts a strange and complex friendship with student Milo Mangasha, an expert in hacking and former fictional pupil of my old school William Ellis, a world of pain and controversy is unleashed. There is a surprisingly key role for Flynn’s Islington sitting tenant Mrs Voyles, who is like a more demented version of Alan Bennett’s “lady in the van”.

The novel is set over one explosive year and divided into five sections – spring, summer, autumn, winter and realisation – and involves a huge, sweeping cast of interesting characters, from north London gangsters to dukes and duchesses. Perhaps, like me, you’ll be skipping back and forth regularly to the glossary of characters at the start of the book.

Although Caledonian Road is long – 656 pages – it gives space for O’Hagan to triumph in the incredibly difficult task of entering our deranged times, writing about them with powerful insight and humour, and never settling for easy answers. It’s inescapable that the story reflects a society that is blighted by duplicity, hypocrisy, narcissism, and the “endless lightshow of self-value”.

The novel offers an ugly picture of 2020s Britain, with a capital city that is a stinking cesspit of laundering and corruption, run by people who still act as if “Rule, Britannia!” is suitable national muzak, falling back on “a thousand years of bluff and superiority” for their “bulls***ting ways”. O’Hagan portrays a country fronted by “royals for hire” and upper-class crooks (with cosy names such as Nighty and Snaffles) who are in the pockets of “dirty dealing” Russians. These oligarchs throw our aristocrats a financial fish to see them bark like a seal. Meanwhile, in places like the perennially seedy Caledonian Road (familiar, as I grew up in the King’s Cross area), there is a sinking underclass whose youngsters get caught up in vicious gang turf wars in a world of drugs, illegal workers and the misery of human trafficking.

The “culture wars” are also a focus of the book, and O’Hagan neatly skewers liberals who delude themselves that they are doing good when what they are really doing is making themselves feel good by policing vocabulary and being “correctness vigilantes”.

O’Hagan excels at his “deep dive into the nonsense of now”, although it can be almost demoralising to see such an articulate and insightful takedown of the way the world is at the moment: the obsession with celebrity that is “a sort of madness”, a digital age where “everybody’s Sherlock on the internet” and one in which technology has destroyed all sense of reason and people “see no difference between accusations and evidence”.

Caledonian Road also squarely confronts how much class is still a factor in why we are such a broken country. It’s witty, too. I’m sure I would be branded “common” by the standards of newspaper columnist Lady Antonia Byre, wife of the corrupt retail tycoon Sir William Byre, because I do quite like mushrooms in my bolognese.

One phrase O’Hagan uses – “moral dementia” – kept coming back as I pondered on this brilliant, disturbing novel. The plot remains gripping to the end, and the author ties everything together with a sly, brilliantly fitting ending which is bang on the money.

‘Caledonian Road’ by Andrew O’Hagan is published by Faber on 4 April, £20

Twelve Sheep: Life Lessons from a Lambing Season by John Connell ★★★★☆

What are any of us doing with our lives? It is a question, says Connell, that we must all work out for ourselves at some point. Connell, a former film producer and investigative journalist, found his calling in bringing lambs into the world and “becoming part of the great symphony of life” on his farm in County Longford, Ireland.

I loved Twelve Sheep: Life Lessons from a Lambing Season. It is, in some ways, a memoir about his own struggles with depression and how he used those difficulties to give him “an opportunity to change a life that was not working”. As well as small nuggets about sheep (I learned about how pregnant ewes are scanned and that sheep will demolish a laurel bush if given the chance), the book is interspersed with meaty anecdotes and reflections – including on a Mexican migrant worker called Maria Gonzales, whom Connell encountered during his work as a journalist. I liked his musings on a painting by August Friedrich Schenck (called Anguish) of which, the author notes, “It is sad but it is real and that counts for something in an at times unreal world.”

Twelve Sheep is a small gem, full of quiet wisdom and gorgeous descriptions of the wonder of nature, the redemption it holds, and how the landscape is charged with meaning.

It’s been a long time since I read such a positive book.

‘Twelve Sheep: Life Lessons from a Lambing Season’ by John Connell is published by Allen & Unwin on 4 April, £12.99

Reading Lessons: The Books We Read at School, the Conversations They Spark and Why They Matter by Carol Atherton ★★★★★

From brief times working in secondary schools (teaching A-level at a posh girl’s school in Hammersmith in my early twenties and then, in my fifties, working with English departments with special educational needs pupils at state schools), I can vouch for Atherton’s assertion that time in the classroom gives people the “ability to spot character types”.

Atherton, head of English at a secondary school in Lincolnshire, must be an inspiring teacher if her marvellous book Reading Lessons is anything to go by. The book is part memoir, part love letter to teaching (such an essential and difficult job) and also a profound and empathetic guide to the literature studied in our classrooms, full of shrewd asides from a sensitive reader.

Atherton explains why books are relevant to a 21st-century fully digital generation (how extremist social media influencer Andrew Tate is like the Duke of Ferrara from Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess”, for example) and explains the importance of reading against the grain and how great books can help youngsters to think and decide for themselves about complicated, ambiguous moral problems.

I’ve seen for myself how good teachers can get sceptical youngsters invested in “old” fiction – such as Macbeth, An Inspector Calls, Jane Eyre and Lord of the Flies – and help, as Atherton puts it, with their “emotional maturity and willingness to make leaps of imagination”.

I hope this isn’t making the book sound dry, because it’s not. It’s highly entertaining, and her chapters on Oranges are Not the Only Fruit, Great Expectations and Of Mice and Men are wonderful. She also pays tribute to Malorie Blackman, stating that “There’s no doubt whatsoever that Noughts & Crosses has been instrumental in getting a whole generation of young readers to see the world differently.”

Atherton, who deals with her own time at state school and then university days at Oxford, will make you want to read or re-read the books she analyses. She reminded me of the power and beauty of Barry Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave, and how, in the loathsome Mr Sugden, the author created “the proxy for every hated PE teacher who has ever existed”. Hands up if you knew one of those (I certainly did).

I was stopped short by Atherton’s passing reference to David “Dai” Bradley, who played the young Billy in Ken Loach’s brilliant, heartbreaking 1969 film adaptation Kes. “David says he still can’t watch the last 20 minutes, over 40 years later: it still upsets him too much,” she relates.

Reading Lessons, full of gritty personal anecdotes, is an engrossing book and a testament to a life well lived by Atherton.

‘Reading Lessons: The Books We Read at School, the Conversations They Spark and Why They Matter’ by Carol Atherton is published by Fig Tree on 4 April, £18.99

James by Percival Everett ★★★★☆

Everett’s new novel James puts the escaped slave Jim from Mark Twain’s 1884 novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at the centre of a droll, clever and enlightening novel.

“I read Huck Finn 15 times, for the purpose of becoming sick of it and abandoning Twain’s story. In my novel, Huck is there, the two conmen are there, but all the characters are completely different,” said Everett. “Most of my novel, since it’s from Jim’s point of view, really has no source in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Huck isn’t always present during my version of Jim’s story in the same way that Jim isn’t always present in Twain’s story of Huck.”

Everett is a genuine literary star. His novel Trees was Booker shortlisted, and the adaptation of his novel Erasure (into American Fiction) recently won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Cord Jefferson. Everett is a brilliantly sardonic writer, evident again from the opening page of James and a joke that for African Americans, “it always pays to give white folks what they want”. There is a memorable scene in which a slave called Lizzie advises her friend on the tactics of dealing with white bosses who “need to know everything before us”. The novel is all about the power that comes with owning the language.

Twain could not (would not) have ever told James’s story, but this is less a novel about the institution of slavery than it is about Jim and his place in the American literary landscape, even though it has important things to say about the degrading way that people have been treated in America. As the novel heads towards a violent conclusion, a chained-up slave tells James: “They’re afraid of us... they think it makes us feel more like animals. So we can mate like animals.”

Everett has written another lacerating, enjoyable novel.

‘James’ by Percival Everett is published by Mantle on 11 April, £20

The Sleepwalkers by Scarlett Thomas ★★★☆☆

The television drama The White Lotus showed the continuing appeal of holidaymakers and couples spraying their psychological and social dysfunctions in exotic places. When volatile newlyweds Evelyn and Richard arrive on a small Greek island for their honeymoon, their fragile relationship implodes, in Thomas’s nifty, Gothic-styled thriller The Sleepwalkers, which is set during an impending seasonal storm.

The “truth” of the young couple’s troubled relationship is revealed in lengthy epistolary confessions written by the husband and wife, with mobile phone transcripts and hotel guestbook pages thrown into the mix.

The novel is partly about their secrets – the ones that are hidden deep in the origins of Evelyn and Richard’s romance – and those of a couple known as “the sleepwalkers”, who previously stayed at the isolated Villa Rosa hotel and drowned. Add to that the creepy hotel owner Evelyn and her mysterious, motley group of helpers and friends, and you have the makings of a mystery.

The novel rattles along, and Thomas seems happy to demand a willing suspension of disbelief at some of the plot devices. I will leave it to women to judge the validity of Evelyn’s confession that, “when we made love that night, I pretended you were your father. A harmless and natural fantasy I’m sure most girls have.”

Her novel is full of similes, including a sly one about Evelyn’s ghastly mother-in-law (“her voice booming like a master of hounds”), and the writing is always polished – even if it does sometimes feel like Thomas, who lectures in creative writing, is doing literary training drills. There is even a passage, about playwright Evelyn and Richard rowing, where Thomas, author of 2019’s Oligarchy, plays around with an inside joke about “the kind of bad writing” that uses “pathetic fallacy”... just as lightning strikes.

The Sleepwalkers should prove to be an attractive summer holiday read, and the author is certainly not afraid to go to dark places in the way she deals with themes such as secrets, lies, sexual assault and human exploitation.

‘The Sleepwalkers’ by Scarlett Thomas is published by Scribner on 11 April, £16.99

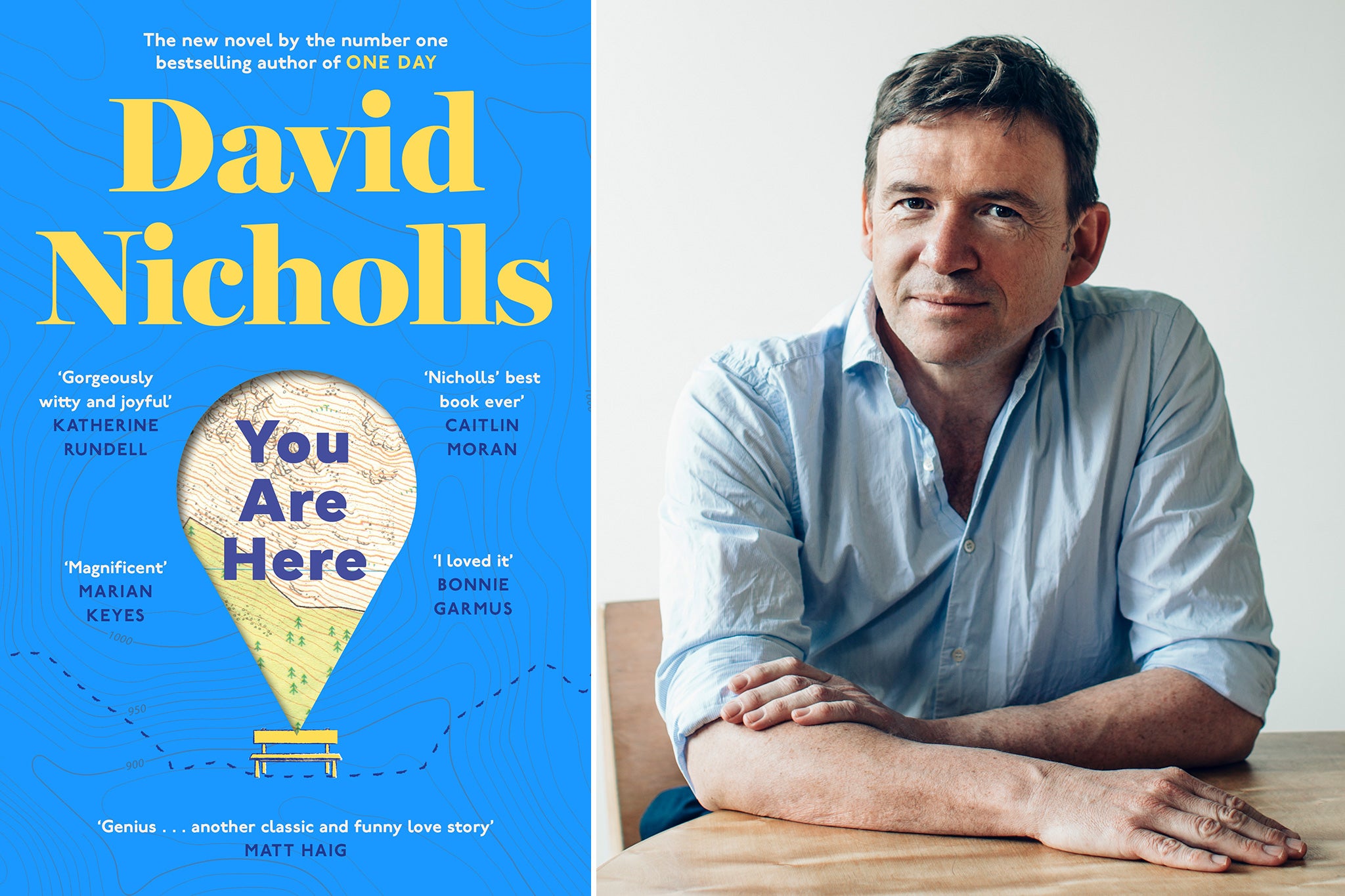

You Are Here by David Nicholls ★★★★☆

The recent Netflix adaptation of the 2009 novel One Day offered a reminder that Nicholls excels at writing about the complexities of relationships. In his new novel You Are Here, his will-they-won’t-they protagonists are the (almost) middle-aged Marnie and Michael.

Marnie is a freelance copy editor and “a people-pleaser, though no one ever seemed that pleased”, and is recovering from a messy divorce. Michael, who has recently split from his wife, is a geography teacher recovering from a trauma.

Their busy mutual friend Cleo (a well-meaning busybody) invites her “Eleanor f***ing Rigby” pal on a walking trip in the Lakes, knowing that she will have the chance to meet new men. Ah, but will it be pharmacist and Formula One bore Conrad, or the odd, bearded Michael who has the answer to where all the lonely people belong?

There is an appetising tone throughout the novel, which is full of clever, droll jokes about teaching, relatives, walking, friendship, pubs and motels. One jest, about breakfast fibre, will have any honest middle-aged male reader nodding sagely.

‘You Are Here’ by David Nicholls is published by Sceptre on 23 April, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks