Book of a lifetime: Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

From The Independent archive: Russell Kane has spasms of erotic delight as he recalls the forbidden ‘first great modern novel’ – an exquisite balance of literary perfection, poeticism and detached irony

After sneaking onto a literature degree via a comprehensive, I found myself nonplussed by the rules and exclusions.

Authors from the English-speaking canon were permitted for my relish. Arbitrarily, so were the Russians. Ladlefuls of Tolstoy, Gogol and Dostoevsky dribbled down my chav parvenu chin. However, stuck in slow recovery from my adolescence and being told certain things were “off limits”, I suddenly desired only those. I mean, of course, French books.

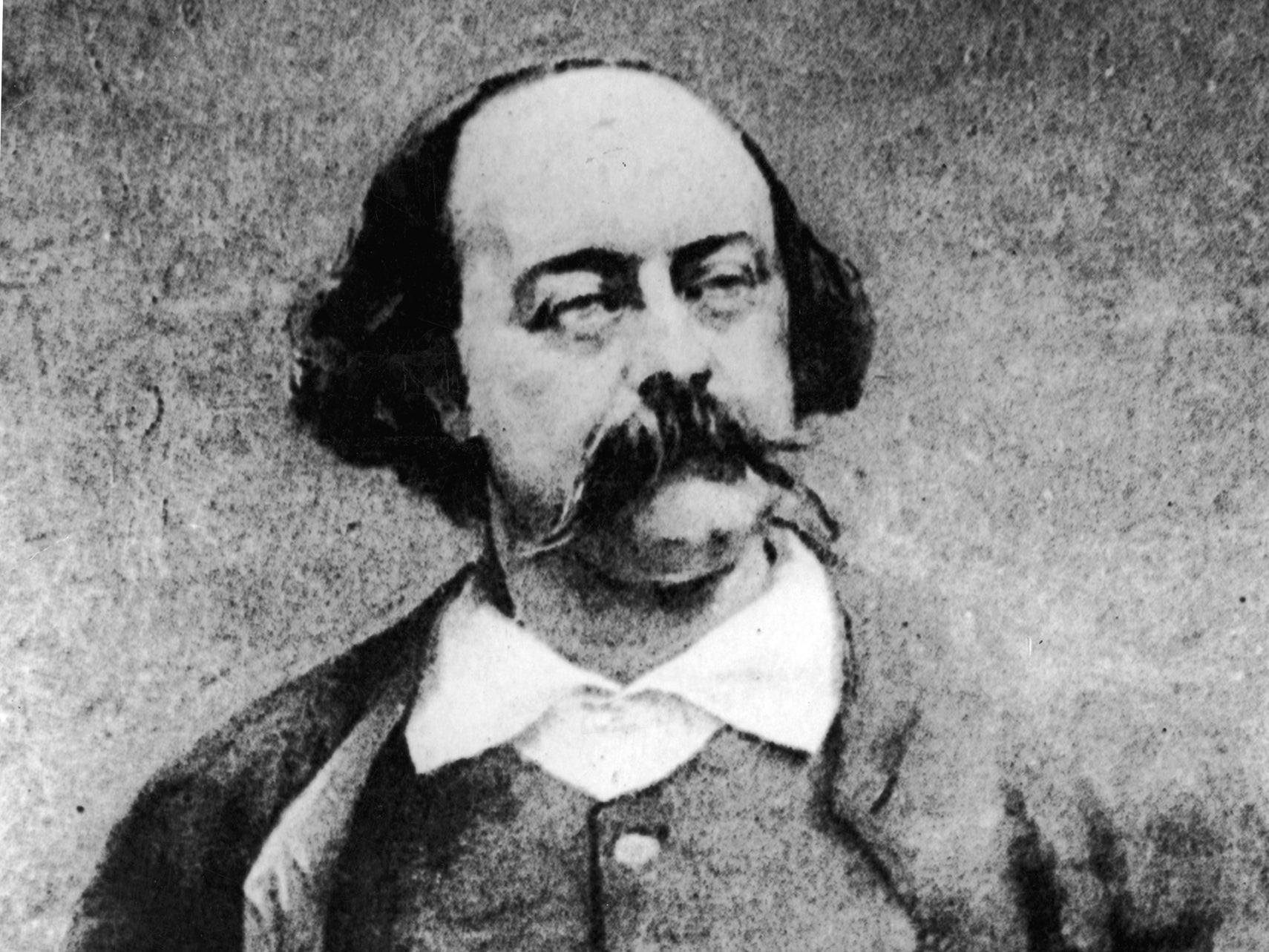

It pleased me in a 19th-century way that “French authors were forbidden”. I didn’t speak French, wasn’t studying it, but, et alors, Flaubert is the master: the writer of the first great modern novel; the author of Madame Bovary.

I can still feel the gooseflesh of my first reading. The story is relatively simple. A well-meaning, but bland and parochial, village doctor falls in love with a sizzling hottie from the next village, the well-brought-up daughter of a farmer. One of Charles Bovary’s first encounters, where curacao dribbles down Emma’s chin in the fetid stale heat of the kitchen, still sends spasms of erotic delight. As soon as they marry, she Vesuviuses into an affair-having, debt-mongering passionate wooooman. It all ends, as it must, in tragedy and death – her fire so raging it burns her and everyone else.

What leaves me reeling with each re-reading (and Adam Thorpe’s translation is, pardon the pun, to die for) is the use of language. There can be no doubt as to the reason for Flaubert’s brain popping at the top of the stairs when he was 58. He broke it scouring for perfect sentences, words, le mot juste. In the seven years he took to write Bovary he spent most days at the bottom of his garden in Croisset – roaring with rage as he “lucubrated” for the optimal poetic expression. He hated cliche, refusing to use assonance – because “that’s what one would do”. His hatred of stock expressions reached its climax in his last work, a satirical list: The Dictionary of Received Ideas.

The language he uses to tell the story of Emma and Charles make me want to hang myself with inadequacy. He ballets a knife-edge between literary perfection, poeticism and detached irony. That he reconciles these styles shows his greatness. One of my favourite lines in all literature describes someone passing out: “The carter came to, but Justin’s faint persisted, with his pupils disappearing into the white sclera of his eyes like blue flowers into milk.”

Blue flowers into milk!!! Take that, Baudelaire – sorry, I mean, Wordsworth.

Emma Bovary’s tragic impulsion towards meretricious passions is more relevant than ever today. Read it. Read it until your eyes turn into your head like... like... Oh, sod it. It’s not easy, is it?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments