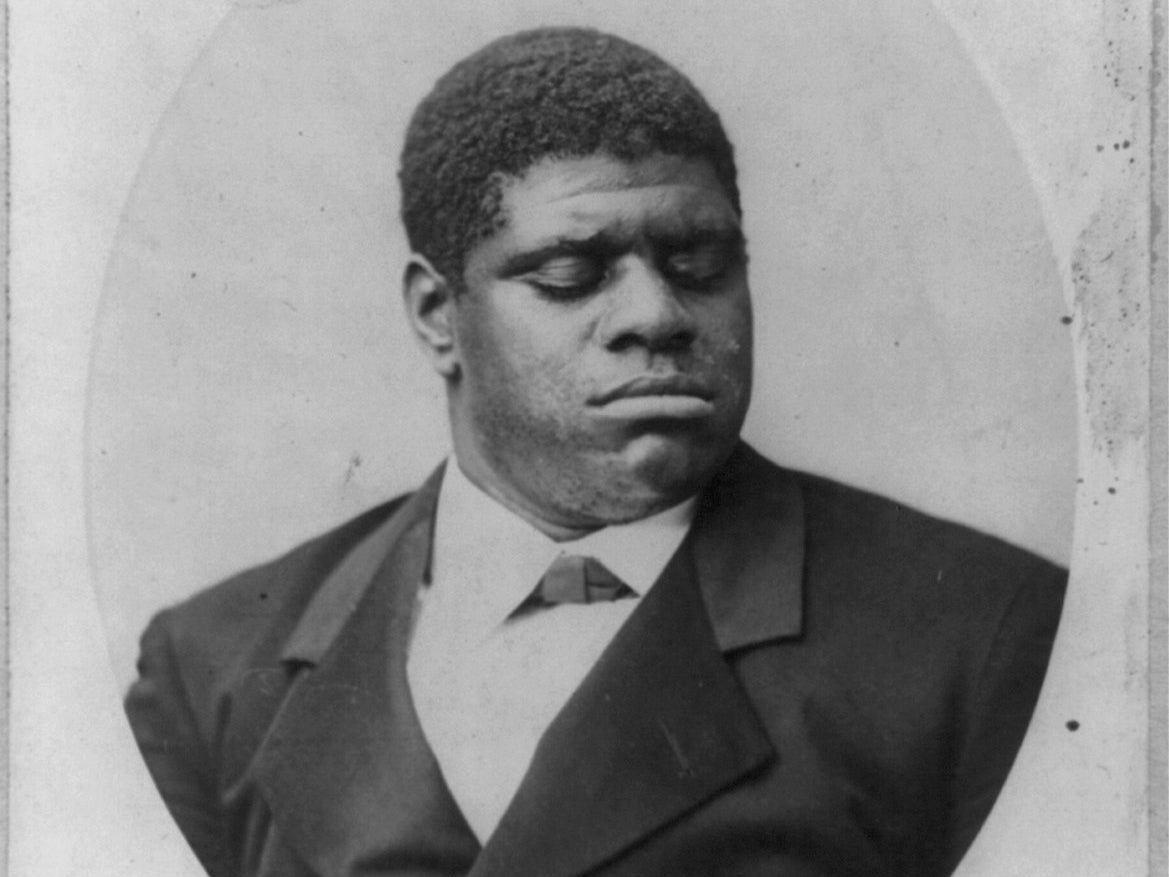

‘Blind Tom’ Wiggins: The musician born into slavery who achieved stardom

He wrote from the age of 5 and toured Europe at 16 as the Wonder of the World… but to others he was an ‘idiot’ and ‘imbecile’, writes Anthony Tommasini

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Charity Wiggins, a slave on a Georgia plantation, was 48 in May 1849, when she gave birth to a baby boy.

The child, whom she named Thomas, was born blind, and she feared that their owner would deem him a useless burden – with potentially dire consequences. Sure enough, before long her family of five was put up for sale to settle some of the owner’s debts.

Wiggins made a bold plea to General James Neil Bethune, a fiercely pro-slavery lawyer and newspaper editor in Columbus, Georgia, to keep her family together. Probably out of pity, he agreed and bought them. He could not have imagined that acquiring the Wiggins slaves would make him a fortune.

Within a decade, Wiggins’s son had become a touring musical phenomenon, reportedly earning up to $100,000 (£723,000) a year, well over $1m today and enough to make him among the best-compensated performing artistes of his time. Under the stage name “Blind Tom” Wiggins, he played his own compositions and improvised on the piano, demonstrating uncanny skills at replicating, note for note, pieces he’d heard – both classical works and popular songs.

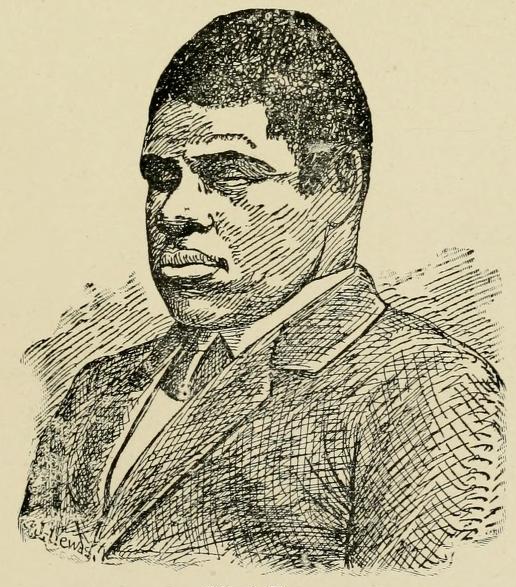

One of his tricks involved playing “Fisher’s Hornpipe” with one hand and “Yankee Doodle” with the other, while singing “Dixie”. He could repeat political speeches he had heard months before, mimicking the vocal cadences of the speaker, even in foreign languages unknown to him.

There are countless testimonies to his fathomless skills, even if they often reek of paternalistic or white supremacist attitudes. During a tour to Europe when Wiggins was 16, he won praise from major musicians. Bohemian (Czech) composer and pianist Ignaz Moscheles deemed him a “singular and inexplicable phenomenon”. Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, though insisting that Wiggins was no prodigy in the traditional sense, described him as a “marvellous freak of nature”. Mark Twain followed Wiggins’s career.

Although his talents were astonishing, Wiggins’s concerts became outlandish spectacles. He had a habit of gyrating and moving his body spasmodically while performing and even while being promoted as the Wonder of the World , many described him as an “idiot,” even an “imbecile” (it is possible that he was on the autism spectrum).

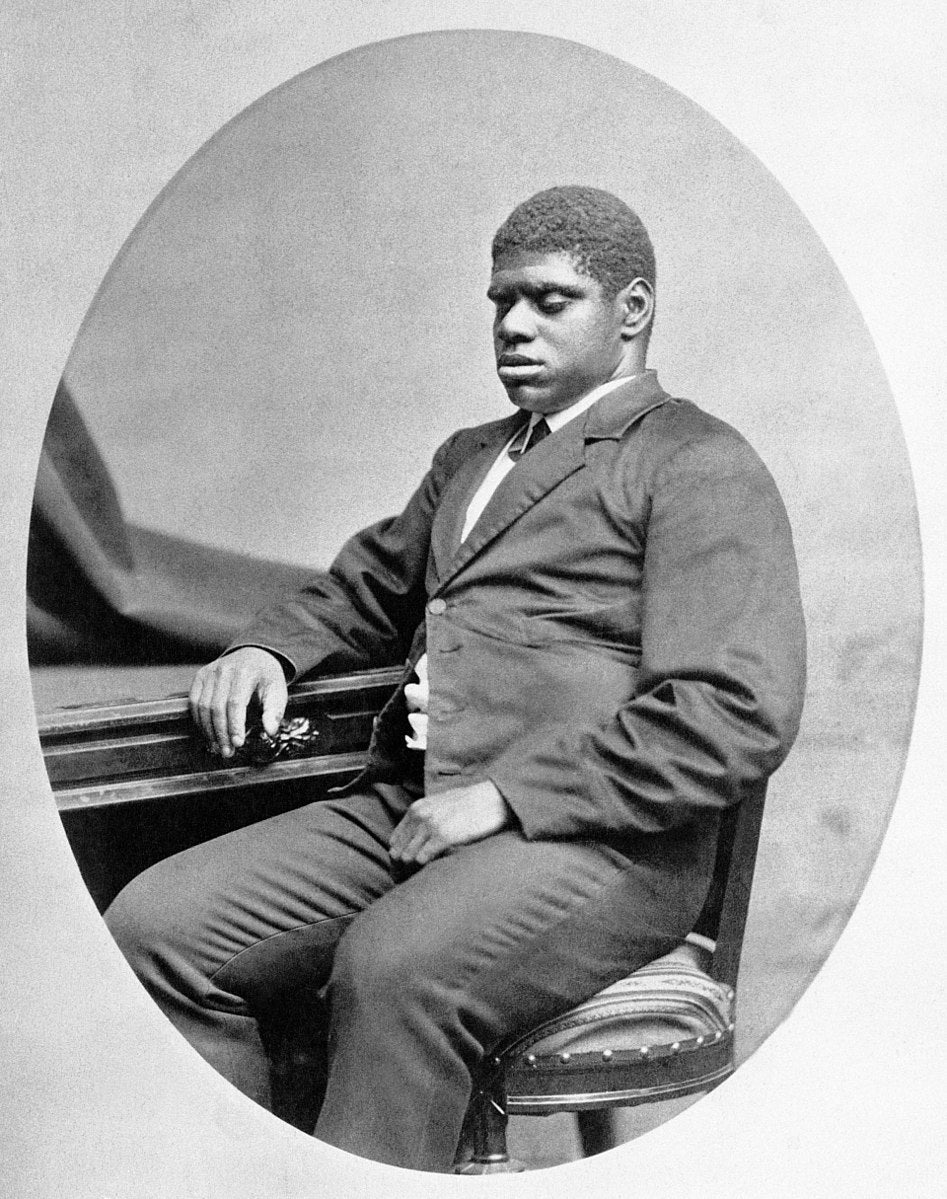

Very little of his enormous earnings went directly to him. Bethune signed a contract with an ambitious promoter. After emancipation, Wiggins remained, essentially, an indentured servant to Bethune, who eventually became his legal guardian.

Wiggins used cluster chords many decades before Henry Cowell was credited with inventing the technique

Wiggins’s life is shrouded in misinformation and exploitative mythologising. From what is known, as a young boy he could barely walk or express his needs but he had an obsession with sounds: rain, wind, clanking tools, kitchen pans, roosters crowing, rattling chains and especially clapping, shouting, songs and music. He soon became a kind of mascot at the main house when the young Bethune daughters sang and played the piano and he listened, seemingly in ecstasy.

Wiggins was allowed to plunk out notes and pound the keys on the piano. One day, without warning, he started playing a piece he had heard one of the daughters practising. The near 50-year career of “Blind Tom” Wiggins had begun.

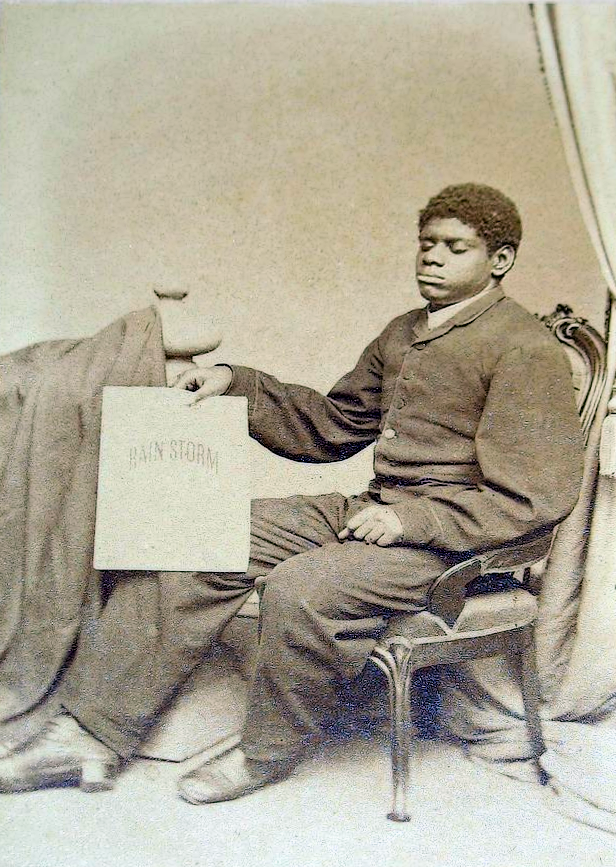

Perhaps the truest insights into Wiggins’s music – and, in a way, his life – are the compositions he wrote from childhood, which were transcribed by a series of tutors who sometimes joined him on the road and who attested to their authenticity. Many were published and circulated widely during his prime performing years.

He and his works have been gaining increasing attention in the 21st century, including an informative biography by Deirdre O’Connell published in 2009, building on earlier work by musicologist Geneva Handy Southall. John Davis made a pioneering recording of 14 works by Wiggins in 1999 on the Newport Classics label – a labour of love that includes extensive liner notes, including essays by neurologist Oliver Sacks and writer and activist Amiri Baraka.

Among the pieces are bewitching scores such as “Oliver Galop”, “Virginia Polka” and “The Rain Storm”, which evoke 19th-century classical styles as well as parlour songs and dance music of the day. Davis also offers a compelling account of Wiggins’s most remarkable piece, “The Battle of Manassas”, a nearly eight-minute work written around 1863 when he was 14 that evokes the first major victory of the Confederate army, an event that had been recounted to Wiggins in detail.

That piece was a high point of a live streamed recital that Jeremy Denk gave in October at the Caramoor arts centre, New York State. Denk had not known of the work before reading about it. Composer George Lewis had proposed a new repertoire of works, old and new, by Black composers. In a short conversation with Lewis paired with his Caramoor performance, Denk describes “Manassas” as a fascinating example of “modernism before its time”. The score is run through with dissonant harmonies and bold juxtaposition of incongruent materials.

The piece opens brutally, with the sounds of cannons and trampling feet suggested through low, rumbling cluster chords that Denk plays with his whole hand or fist (Wiggins used cluster chords many decades before Henry Cowell was credited with inventing the technique).

Over these chords we hear, in the high register, the sprightly tune, “The Girl I Left Behind Me”, and, soon after, “Dixie”.

Episodes follow with the sounds of fife-and-drum marching tunes, bugle fanfares and, suddenly, echoes of Chopin-esque lyricism, like melancholic parlour songs. Could this be nostalgia? A transitional passage of shimmering high tremolos leads to the “Marseillaise”, of all things, played in full chords over a stride-like accompaniment, though rumbling clusters down below just will not stop. The ending – “shocking for its time,” Denk said – depicts the retreat of the Union forces and is a teeming apotheosis, with the national anthem sounding in rolled chords, incessant low clusters, a reprise of the “Marseillaise”, furious outbursts of oscillating Lisztian octaves and a curious fadeaway.

In his newspaper article, Lewis had an explanation for the seeming incongruity of a Black composer, born into slavery, celebrating a moment of triumph for the Confederacy. Lewis wrote that the work can be heard today, “as an anticipation of that regime’s collapse – and as a soundtrack for the decommissioning of Confederate statues, those physically imposing paeans to Jim Crow that merely posture as history”.

Denk agreed, in his conversation with Lewis, that irony runs through the music, comparing it to Shostakovich, who folded marches and brass odes to victory into his symphonies that, if you are so inclined, come across as bitter embedded protests against the repressive Soviet regime.

A complex man who listened to the turbulent world around him and reflected it in sound

Davis similarly says that, for all its “surface naiveté”, there is a “subversive quality”, a “darker underpinning”, in much of Wiggins’s music. But how conscious might Wiggins have been of his audience and the effects of his music.

Hw says: “It’s open to question. What was his conception of his condition and his predicament as a slave?”

Davis is planning to record other, little-known Wiggins works. He says that their composer may well have had emotions he was incapable of expressing. His physical gyrations were seen by racist audiences at the time as evidence he was primitive. Yet Davis points to another blind pianist from Georgia, Ray Charles – who, when he expressed himself through involuntary physical mannerisms, was, “taken as the ultimate in rock ’n’ roll hip”.

For some listeners, several of the pieces on Davis’s album might seem pastiches but there are subtleties and deep expression in many of these works. “Cyclone Galop” begins with a wistfully lyrical introduction that leads into an up-tempo yet restrained dance with a charming melody. It’s like an amalgam of Donizetti and New Orleans Music Hall. Yet even this light-seeming romp has rich emotional texture.

“The Rainstorm” [one word on Davis’s album], reportedly composed when Wiggins was five, is both beguiling and dramatic. It opens with a swaying melody over an oompah accompaniment. Suddenly, there are low tremolos indicating rumbling thunder and ominous roiling chromatic riffs in the bass, like the brewing storm music near the end of Verdi’s Rigoletto. There are bursts of vehement octaves before the tension subsides, with parallel intervals creeping up into the piano’s high range. And then the dancing music returns.

“Sewing Song” depicts the mechanical sounds and rhythms of a device that clearly hooked the young Wiggins. Delicate arpeggios set the mood, followed by a wandering melodic passage, until we hear rustling figures that spin and flow in the high register of the piano almost continuously. Right through, in the middle range, a sad melody with tender chords unfolds.

Even in these evocative, lighter works, I hear lyrical flights, layered textures and intensely dramatic juxtapositions – the myriad expressions of, “a complex man who listened to the turbulent world around him and reflected it in sound”, as O’Connell put it in her biography.

A heartening turn in Wiggins’s life came in the mid-1880s, when Bethune’s son John, who was Wiggins’s guardian and primary exploiter, died in an accident. Eliza Bethune – John’s disgruntled widow after a short-lived marriage, miffed about being left out of his will – went to court to wrest Wiggins from the Bethune family and gain guardianship, a suit supported by Wiggins’s mother. Eliza won.

But Wiggins, unhappy with his new guardian, essentially refused, with scant exceptions, to perform for the next two decades, until his death at 59 in 1908 in his apartment in Hoboken, New Jersey. It may have been the final act of defiance of a figure whose life and work remain unsettled, ambiguous, compelling and worthy of even more attention.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments