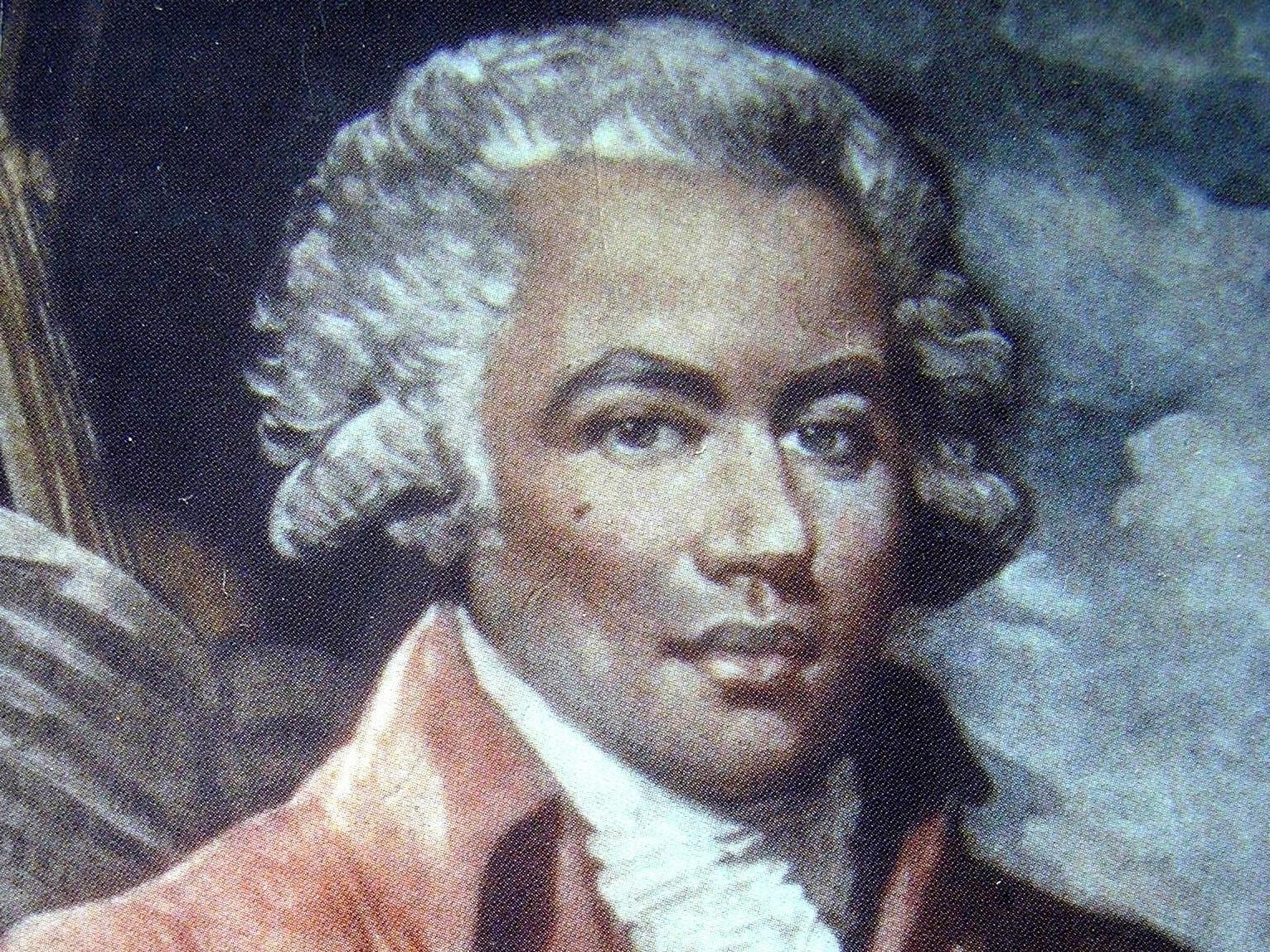

Composer, swordsman, polymath: Why Joseph Boulogne should never be called the ‘Black Mozart’

The unwanted moniker subjugates ‘Chevalier de Saint-Georges’ to an arbitrary white standard, writes Marcos Balter, and erases his unique place in classical music

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last month, Searchlight Pictures announced plans for a movie about Joseph Boulogne, the 18th-century composer also known as Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

When the announcement was made, headlines resurrected yet another moniker for Boulogne: Black Mozart. Presumably intended as a compliment, this erasure of Boulogne’s name not only subjugates him to an arbitrary white standard but also diminishes his truly unique place in western classical music history.

Few musicians have led a life as fascinating and multifaceted as Boulogne’s. Recounting it, however, is an exercise in educated guesswork. What is known is scantily and contradictorily documented, when not purely anecdotal. To make matters worse, a 19th-century novel by Roger de Beauvoir, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges, intertwined fact and fiction so seamlessly that many of its fabrications gradually found a place in Boulogne’s assumed biography.

What we know is that Boulogne, the son of a wealthy French plantation owner and an enslaved African woman, was born between 1739 and 1749 on Basse-Terre, the western half of the island archipelago of Guadeloupe. When he was about 10, he and his mother followed his father and the rest of his family back to France, where Boulogne was enrolled in elite schools and received private lessons in music and fencing.

His first claim to fame was as a champion fencer, the best-known disciple of the master La Boessiere. A painting depicting a match between Boulogne and the Chevalier d’Eon is on display at Buckingham Palace.

Boulogne’s extraordinary fencing talent led Louis XV to name him Chevalier de Saint-Georges, after his father’s noble title, even though France’s Code Noir prohibited Boulogne from officially inheriting the title because of his African ancestry. He earned a nearly mythical status even across the Atlantic: John Adams described him as “the most accomplished man in Europe in riding, shooting, fencing, dancing and music”.

Little is known about Boulogne’s musical training. But when Francois-Joseph Gossec, one of France’s pioneering symphony writers and most prominent conductors, founded the Concert des Amateurs series in 1769, he invited Boulogne to join its orchestra, first as a violinist and later as its concertmaster.

Boulogne’s first documented compositions are from 1770 and 1771. While these are clearly works by a composer still searching for his voice, they demonstrate his commitment to the new and unexplored. The six string quartets of his Opus 1 were among the first in that genre to be written in France. His three sonatas for keyboard and violin (Op 1a) feature those instruments as equals, breaking away from the Baroque tradition of basso continuo, which was still very much in vogue. His harmonies, textures and formal schemes place him within a classical style that was still forming.

His first public and critical success as a composer came with his two violin concertos (Op 2), which premiered in 1772 at the Concert des Amateurs series, featuring Boulogne as soloist. The level of craft and sophistication in these pieces far surpass his efforts of the previous two years. The particularly beautiful Largo movement of the second concerto features many trademarks of his later style, including a penchant for whimsical colours that run the range of instruments and an understanding of how to balance orchestral forces with clarity.

It is a remarkable fact that his music has survived two centuries of neglect caused by the systemic racism that permeates the notion of a western canon

When Gossec was invited to direct the Concert Spirituel series in 1773, he named his concertmaster as his successor. Under Boulogne’s direction, the Concert des Amateurs orchestra became widely regarded as the best in France, if not all of Europe. His raised profile as a conductor led to an invitation in 1775 to apply for the directorship of the Academie Royal de Musique, the country’s most prominent musical position. His candidacy, however, was crushed by a petition to Marie Antoinette from a group of performers who objected to “accepting orders from a mulatto”.

Also in 1775, he wrote two symphonies concertantes for two violins and orchestra (Op 6), his initial contribution to a genre he and other French composers of the time helped define. A hybrid of the Baroque concerto grosso and the classical concerto, a symphonie concertante usually featured two or more soloists in a virtuosic dialogue that emulated a musical duel. Boulogne wrote eight such pieces between 1775 and 1778, a testament to the demand for them among French audiences.

In 1778, Mozart travelled to Paris, staying from March to September and briefly under the same roof as Boulogne, hosted by Count Sickingen. It is implausible, to say the least, that Mozart did not hear Boulogne’s music during this period. Intriguingly, Mozart’s first composition after his return to Austria was his Symphonie Concertante in E-flat (K 364). And in an article published in 1990 in the Black Music Research Journal, Gabriel Banat points to the remarkable similarities between an excerpt from Boulogne’s Violin Concerto (Op 7, No 2) from 1777 and a passage from Mozart’s K 364 from the following year. The gesture in question recurs in Boulogne’s solo string writing – a difficult sequence climbing to the highest register of the instrument, immediately followed by a dramatic dip – but had never appeared in Mozart’s work until this Presto.

When lack of funding forced the Concert des Amateurs to end in 1781, Boulogne and his musicians found a home with the newly formed Concert de la Loge Olympique, which quickly gained a reputation as the best orchestra in Europe. It was under this umbrella that Boulogne conducted the premiere of Haydn’s six Paris symphonies, among many other important commissions.

Discouraged by his persistent lack of success in opera, by dwindling patronage because of changes on the political scene and by his increased activism in the French Revolution as an enlisted officer, Boulogne sharply reduced his musical activities towards the end of his life. He died in 1799, not a penniless man but certainly a far less relevant and valued figure in French society than he had been a couple of decades earlier.

Nevertheless, his influence in France and abroad, both as a curator and a creator, was felt long after his death. It is a remarkable fact that his music has survived two centuries of neglect caused by the systemic racism that permeates the notion of a western canon. Neither his omission from music-history textbooks – of the two most used in America, he gets a brief, vague mention in one and is absent from the other – nor a lack of advocacy from programmers, publishing houses and record labels has erased him completely.

This is the ultimate proof that Boulogne doesn’t need to be anyone’s second best – let alone anyone’s black echo. So, yes, I cannot wait to see the movie. But spare me the awful nickname.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

3Comments