Van Gogh Self-Portraits review: An intimate and harrowing look at an artist facing fatal collapse

Comprising only 18 works, this show at London’s Courtauld Gallery is tiny. Yet its emotional scale is massive

It’s hard to imagine a more sure-fire crowd-pulling exhibition than this one. Van Gogh may have peaked as “the world’s favourite artist” (I’m expecting at any minute to hear Andy Warhol is now filling that role), but the Vincent formula of joyful art and tragic life story (he shot himself aged 37) has lost none of its power to compel. Everyone from primary school children to the absolute dons of painting, the Hockneys, Kiefers and Doigs, “loves” Van Gogh. How can you not?

And the self-portraits, where the artist is looking into the depths of his very being, are surely the place to encounter Van Gogh’s art at its rawest and most intimate.

Bringing together 15 of Van Gogh’s 35 painted self-portraits, this exhibition at London’s Courtauld gallery is – incredibly – the first devoted to this aspect of Van Gogh’s art. Since his death, Van Gogh has been retrospectively diagnosed with a whole range of problems, from bipolar and borderline personality disorders to epilepsy, severe alcohol poisoning and sunstroke. During the three years in which the show’s works were painted – 1887 to 1890 – he arrived in Paris, travelled to the south of France where he created his most famous works, mutilated his own ear and checked himself into an insane asylum back in northern France, before killing himself in July 1890. This is, of course, well-trawled territory, and the exhibition adopts a more sober, academically credible approach, wanting to dispel the idea that these paintings are “simply outpourings of raw emotion as the artist faced himself in the mirror” – an idea perpetuated not least by Kirk Douglas’s eye-rolling performance in the film Lust for Life.

Yet while the exhibition just about convinces that Vincent was aware he might be projecting himself in a variety of roles, as a smart-suited bourgeois in one painting or working artist with brushes and palette in another, its chief fascination lies in allowing us to follow the subtly changing expressions in his eyes as he faced fatal collapse, while simultaneously changing the face of European art.

In Self-Portrait with Felt-Hat, the only work representing his dark, Dutch early style, the forceful rendering of the features enhances the confidence of Vincent’s expression. Not a trace of anguish here. Yet within three months, in Self-Portrait Paris (Spring 1887), he has transformed himself from dour northern realist into a “French” impressionist – and completely convincingly. Black has been abandoned in favour of muted lilacs, pinks and blues that sing beautifully together. Yet the look in the artist’s eyes is far more uncertain.

Looking straight out at us a month or so later in Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat (Spring 1887), there’s a touch of mania in his pale eyes – one blue, one green – around which the entire picture seems to radiate. The brushstrokes giving form to the artist’s gaunt features – caused by loss of teeth – beard and clothes create a sense of swarming energy as they flare outwards from the haunted eyes.

Vincent seems to calm down a shade in Self-Portrait Paris (March/June 1887), looking more comfortable as he reinvents Seurat’s pointillism – or dot painting – pulling oranges and greens from the beard and facial features into the pulsing dots of the background, so that every centimetre of the canvas seems in a state of agitated, vibrating life.

Beside this masterpiece, two paintings, both called Self Portrait Paris (Summer 1887), are evidence that Van Gogh didn’t always get it right: the sense of directness and immediacy that marks out his best work is entirely absent. While the show makes much of the symbolism of the headgear in two paintings called Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (August – September 1887) – embodying, it claims, Van Gogh’s “commitment to painting directly in the landscape” – it’s the look in his eyes that unfailingly draws our attention. There’s a touch of fear in the first, and a sense he’s barely holding it together in the second, while the background of the latter, dabbed in a mass of loose kinetic marks suggests he’s effectively inventing Expressionism even as he’s staring into the abyss.

The “swarming” lines seen in Portrait with a Grey Felt Hat are taken to their ultimate in another painting with the same title created six months later (Sept – Oct 1887) with the green and blue lines contouring the eyes and cheeks appearing incised, even tattooed onto the face. While a psychologist might interpret this as evidence of outright mania, the artist’s expression exudes a desperate calm. It’s as though Vincent wants to paint a somewhat more conventional work, and the painting itself is doing its own thing.

Yet the progress towards collapse and death isn’t as straightforward as we might now be expecting. In the show’s poster image Self-Portrait as a Painter (Dec 1887 – Feb 1888), he projects himself as the professional painter, with palette and easel. Yet the painting, built up in his characteristic masses of flickering colour, feels like Vincent on his best behaviour. Trying even at this late stage to extract a buck from his art, he has created something a touch stolid and not quite convincing.

That’s an accusation that can hardly be levelled at Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889) from the Courtauld’s own collection, the work with which most visitors will be familiar. The sense of blank candour as he looks out at us while recovering from the famous ear mutilation is at once terrifying and heart-rending – far more so in this context than in the usual gallery display.

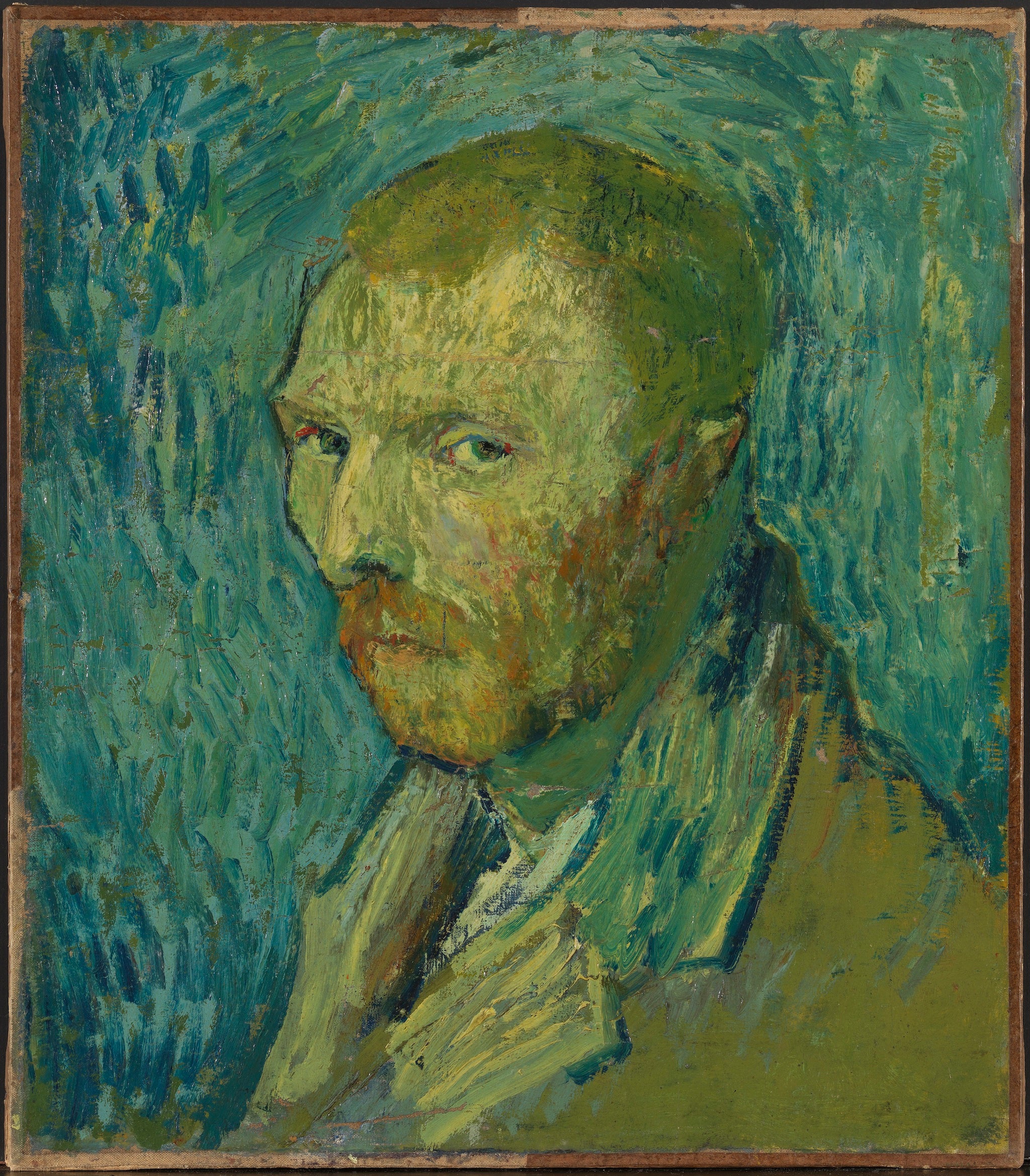

By Self-Portrait Saint Remy (August 1889), painted in the asylum while he was undergoing treatment – “an attempt from when I was ill,” he told his brother – we feel like we’re inside the illness with him. His clean-shaven features tinged a queasy green turn towards us with a spaced out expression that’s as near to non-being – the sense he’s losing his very humanity – as any artist has yet achieved. Only recently authenticated, this painting is the show’s great revelation.

Yet only a week later, Van Gogh reappears almost perky in another Self-Portrait Saint Remy (Sept 1889), once again playing the palette-toting artist. He turns into the green-tinged shadow with an expression that could be interpreted as cocky or outright demonic, in his last self-portrait before he killed himself nine months later.

Comprising only 18 works, this show is tiny. Yet its emotional scale is massive. Every painting here plunges you into a moment in Van Gogh’s final act, when, not entirely paradoxically, he was at his most creatively productive. The effect is at once uplifting and genuinely harrowing. I don’t think Warhol will be snatching Vincent’s mantle quite yet.

Van Gogh: Self-Portraits is at the Courtauld Gallery from 3 February to 8 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks