Roger Mayne – Youth review: Crumbling post-war Britain brought vividly to life

The photographer may not be a household name, but his gritty, monochrome images of 1950s Britain are instantly recognisable, brought together in this lovingly curated must-see show at the Courtauld Gallery

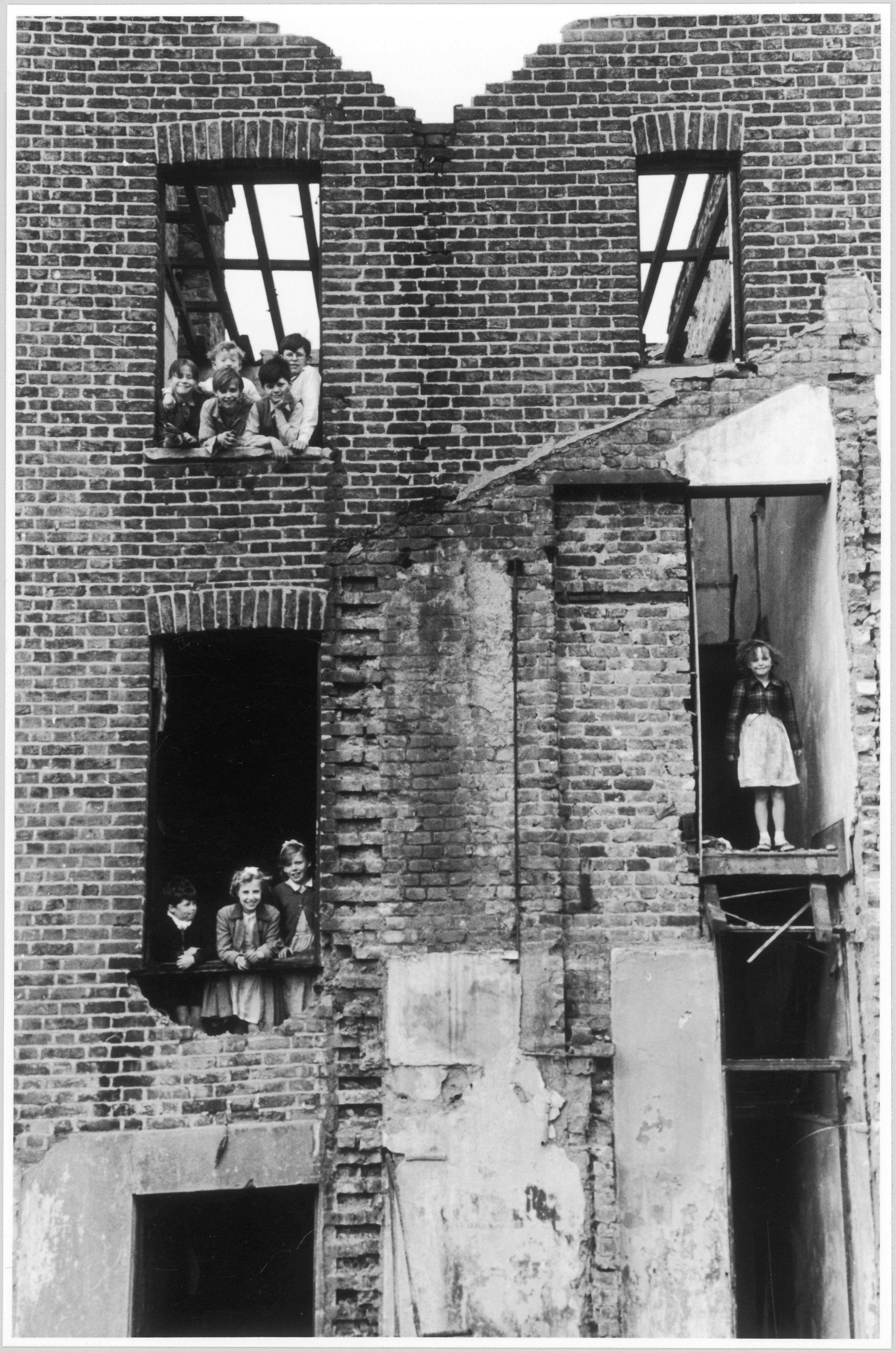

The 1950s: a pivotal moment in British culture, or a dingy interlude before things really got going in the Swinging Sixties? For most of us, the era of smog and food rationing will feel unimaginably remote in time. The mere sight, though, of one of Roger Mayne’s pungent images of children playing along the crumbling terraces of post-war Notting Hill will transport you to a world where everything was grim, gritty and entirely monochrome. And it’s all so vividly captured you can practically taste the acrid fug of massed coal fires – even if you never experienced such things in reality. Yet in spite of – perhaps even because of – this powerful period feel, Mayne’s images make peculiarly apt viewing at the present time.

If Mayne isn’t yet quite a household name, his wonderfully intimate photographs of the inhabitants of Southam Street, an area of condemned Victorian housing in the roughest end of North Kensington have an instantly recognisable texture and atmosphere. They have featured in a plethora of recent books and exhibitions – notably the Barbican’s Postwar Modern show in 2022 – and are becoming established as among the defining images of a time when Modern Britain was emerging from the ruins of the blitz, when the country was getting its first taste of rock’n’roll amid a social order still mired in Victorian inhibition.

Born into an academic family in Cambridge in 1929, Mayne grew up remote from the kind of social environment he became famous for portraying. He became interested in the technical aspects of photography while studying chemistry, before developing an approach to the medium that was very much people-centred. He then spent years looking for a subject worthy of his talents. While his early study of the St Ives artists – the abstract painters working in the far west of Cornwall – offers a picture of a Britain that was embracing new freedoms, Southam Street, which he first visited in 1956, seemed stuck in a groove of Dickensian anti-aspiration in which any attempt at “improvement” felt risibly futile.

The writer Colin MacInnes, whose iconic novel Absolute Beginners (for which Mayne provided the cover image) is set in the area, described it as a “rotting slum of sharp, horrible vivacity… a place the Welfare State and the Property-Owning Democracy equally passed by”. For Mayne, however, it was clearly a place of wonder, with a prevailing warmth and a collective solidarity in which all social interaction, whether between adults or children, took place outdoors, in the shared space of the carless street. Mums chat in the battered porticoes of once grand townhouses, while children clamber on the steps around them, play football, explore bombed-out buildings, and cavort on heaps of rubbish. While there are moments when the subjects are clearly performing for Mayne’s camera – including the little girls rolling around giggling in Children (1956) – generally they seem barely to notice the snapper who spent six years documenting their world.

Where some commentators would have discerned a delinquent unruliness in the cocky looks of some of the boys, Mayne sees self-expression. The dynamic compositions in images such as Girls Doing Handstands (1956) are evidence not just of his creativity, but of theirs. The boys twisting and turning on a heap of old mattresses in Bomb Site, Portland Road (1958), are typical of the figures, “choreographed”, as the wall text puts it, across images that show a painterly feel for the ravaged textures of the post-war city, all battered stucco and graffiti. Mayne, indeed, must have been the first British artist to positively enjoy street art.

The idea that children’s play had social and educational value was becoming fashionable in academic circles and Mayne became the go-to image-maker in social studies and child psychology, as evident in a display of vintage Pelican book covers all featuring his pictures. In that sense his quintessentially Fifties images were already looking forward to the freedom-loving Sixties.

His Southam Street pictures were exciting a sense of nostalgia even as he was taking them, perceived as documentation of a disappearing urban world. Yet for him, they were first and foremost about the relationship between artist and subject. The longer you look into his best images, such as the intensely staring child in Girl on the Steps, St Stephens Gardens, Westbourne Park (1957), the more the social context seems to fall away, and you’re left looking at something completely timeless.

As his subjects grow older, in a section of the show called “Teen Takeover”, there are still remarkable images, such as the wonderfully expressive Girl Jiving, Southam Street (1957), in which the subject clad in her dad’s jacket looks miles away in her own world of rhythm. But generally, his studies of Teddy Boys and Teddy Girls feel slightly more conventional. His photographs of his own children growing up in a bohemian household in rural Dorset are as informal as you could wish for. We’re even shown Mayne’s wife, the playwright Ann Jellicoe, giving birth to their daughter Katkin in visceral close-up. Yet these images, excellent though they are, lack the electrifying tension of his Southam Street photographs. On this showing at least, Mayne never again recaptured that sense of total absorption in another world and another culture.

Mayne takes us to times that were in many ways vastly more challenging than our own, with images of youthful exuberance that can’t fail to lift the spirits – and we know with hindsight that good times were just around the corner. They make for poignant viewing in an era of relative wealth when most of us feel precious little cause for optimism.

Courtauld Gallery, 14 June to 1 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks