David Hockney – Drawing from Life review: He’s as magnetic with a pen, pencil or paintbrush

Moving portraits of his mother. Coloured pencil etchings of his coolly beautiful friend Celie Birtwell. A peppy sketch of a cosily cardiganed Harry Styles. David Hockney’s life in drawing makes for a gripping show at the National Portrait Gallery

David Hockney is justifiably proud of his drawing skills. Like most artists of his generation, he underwent years of enforced practice at art school, drawing from the nude model. This left him with a confidence and fluency in capturing immediate reality with pencil, pen or brush that today’s young artists can only dream about.

This major show of Hockney’s portrait drawings first opened in February 2020 and ran for only 20 days before it closed due to Covid. It reopens at the recently refurbished National Portrait Gallery in a reworked form with 30 new portraits, painted in the artist’s Normandy studio immediately post-lockdown. It provides the perfect opportunity to assess whether Britain’s favourite artist has lived up to his formidable gifts as a draughtsman, or if he’s sold them out in a succession of ever more glib exercises in populism – as some would certainly claim of his experiments with iPad drawing.

A selection of the latter appear in animated form at the beginning of the show: Hockney smoking morphs into Hockney sneezing. They’d be great on children’s TV (if it wasn’t for the smoking), but I couldn’t get more involved in them than that.

Just a few feet away, a life-size painting of Hockney’s parents from his mid-Seventies “Neoclassical” period comes with a more profound inference: that drawing has been the basis of all Hockney’s art, whatever the medium. He’d certainly be the first to endorse that claim. And, with its emphasis on lines and clearly contoured forms, the painting feels indeed like an immense drawing in richly coloured paint.

But the first actual drawings we’re shown are small and very careful pencil self-portraits from the mid-Fifties, when Hockney was still a student in Bradford. He stares back at us through NHS glasses in the dour observational style then de rigeur in British art schools. He soon mastered this and just about any other form of drawing that caught his interest. In a jump forward to the 1970s, two imaginary self-portraits with his hero Picasso demonstrate Hockney’s magpie skill in synthesising visual styles. In Artist and Model (1974) Hockney pictures himself drawn by the great Spanish painter, his naked body evoked in very fine, classically precise lines, while Picasso is portrayed with splashy expressive brushmarks, in front of a starkly simple view through the window in the background. That’s three drawing styles for the price of one, brought together with a twist of Hockney’s inimitably stylish visual wit.

You don’t have to look long, though, to see that this image is an etching, a print that would have required more planning than feels quite permissible in a show devoted to “drawing from life”. Its inclusion feels just about acceptable, given that Hockney probably drew it directly onto the etching plate. But Hockney’s great series of etchings, A Rake’s Progress (1961-3), which hang on the opposite wall, feel like they’re in the wrong exhibition. They’re some of his most brilliant works, an immensely creative exploration of the etching medium. But they are not drawings. Neither it could be argued are the various photo-collages dotted through the exhibition.

The exhibition’s main focus, however, is on Hockney’s portraits of five individuals, each of whom has sat for him over decades: the textile designer Celia Birtwell; his former partner, now curator, Gregory Evans; master printer, Maurice Payne; and not least the artist’s mother and Hockney himself.

The sight of Hockney’s coloured pencil drawings of the coolly beautiful Birtwell sent me tumbling straight down a time tunnel to the early Seventies, when every art student and illustrator in the country seemed to be imitating the highly seductive style employed in these works. Celia in Black Slip Reclining (1973), showing the designer sprawled back on a sofa, feels like an old-school academic drawing with a postmodern twist, evident in the subtle interweaving of colour and a deliberately unfinished quality. It’s as though Hockney decided to just stop mid-pencil stroke – which hasn’t stopped it becoming one of his most popular works.

As with all drawing from life, the success of Hockney’s portraits is very much down to his state of mind on the day. The room devoted to images of his mother begins with some unremarkable works in his coloured pencil mode, before we’re suddenly looking into her anxious eyes in a large crayon drawing from 1994, with the simply drawn but perfectly observed pursing of her lips speaking volumes about the anguish of old age.

Throughout the show, works that are merely so-so contrast with works that are so acutely seen they fairly ping off the wall. While you might imagine that greater quality control could be the answer, that’s not the point: it’s the sense of the whole process, the realisation that no artist gets it right every time, not even Hockney – particularly, perhaps, not Hockney – that gives the show its piquant flavour.

The images of Hockney’s sometime lover, assistant and curator Gregory Evans take in an amazing diversity of mediums from rapid pen-and-ink studies to near-photographic crayon drawings and a very large quasi-Cubist lithograph, though Evans’s wide-eyed, abstracted expression barely changes over the decades. By far the worst are three detailed pencil portraits done after Hockney saw an exhibition on the great French Neoclassical painter Ingres at the National Gallery in 1999. Convinced that Ingres had used a camera lucida – a tiny prism – as an aid to accuracy, Hockney began using one himself. The resulting images look like very dull Ingres pastiches. The moment Hockney loses faith in his own vision, everything goes awry.

The portraits of master printer Maurice Payne, who has printed much of Hockney’s graphic work since the early Sixties, follow a similar pattern of styles and mediums, though these feel the least personal and thus the least affecting works in the show.

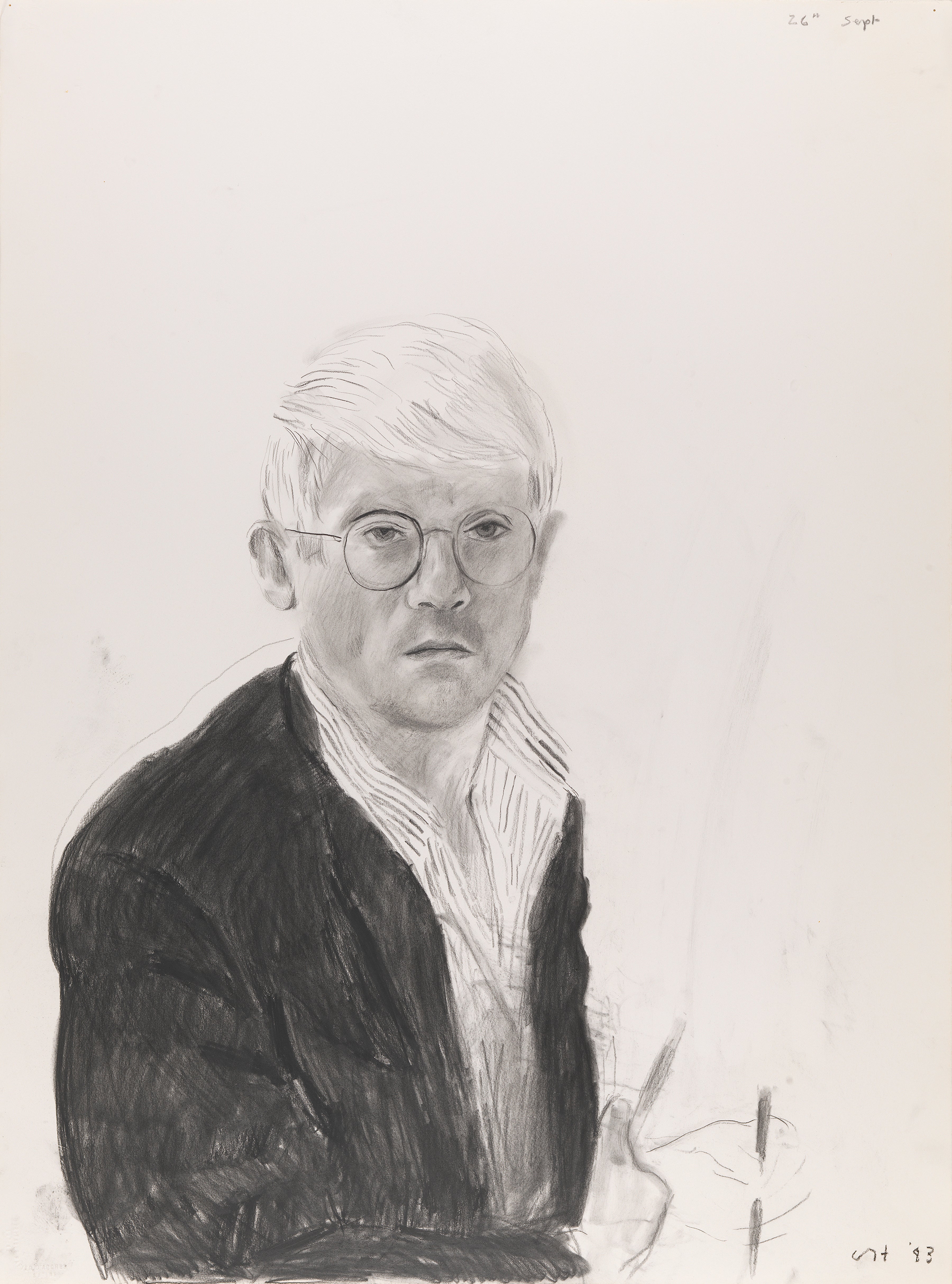

Hockney’s self-portraits are most compelling when he’s least in role as “David Hockney”, which he is a little too much in drawings from the Eighties, wearing that quizzical expression that’s so familiar from television. But by the time we get to the large charcoal drawing Self-Portrait 7 Dec 2012, there’s an unadorned candour to the gaze of the grumpy old bloke looking back at us – and of course at himself – fag in hand, glasses halfway down his nose. This is a hangdog, intimate Hockney you won’t encounter under any other circumstances.

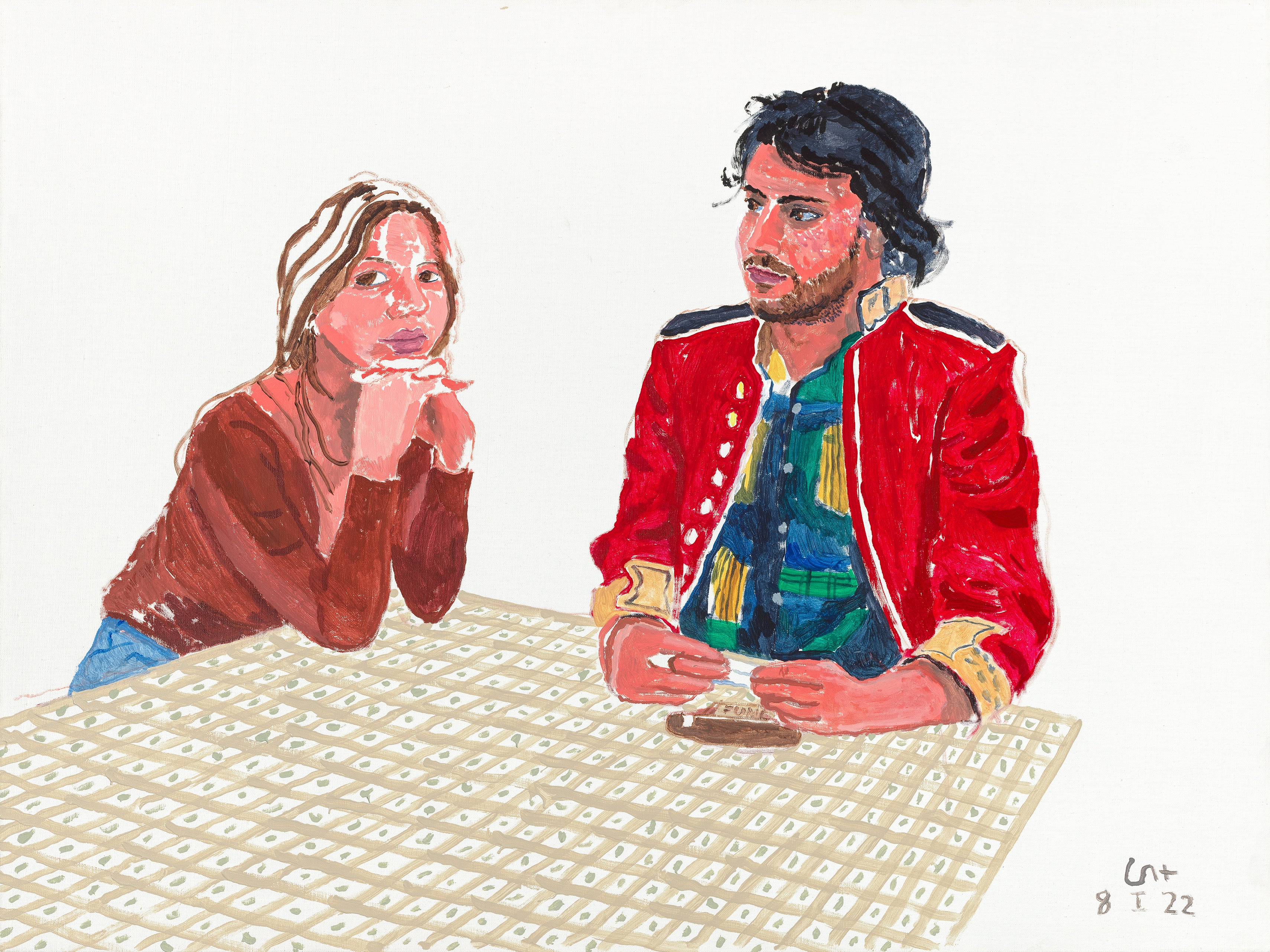

The show ends with the so-called Normandy Portraits: 30 “painted drawings” on white backgrounds, created between 2021 and 2022, showing whoever Hockney was able to summon to his Normandy retreat in that strange post-lockdown period, from Harry Styles in an orange and yellow-striped cardie to Hockney’s gardener seated on his motor mower. I quite liked the gentleman in a blue suit, pictured inclining forward in his seat as though he’s leaning out of the picture towards us. Otherwise, they have a cheerful informality, but even the most die-hard Hockney fan would struggle to make claims for them. The Styles painting is okay, in a sub-A-level kind of way. Maybe Hockney has added “sub-A-level” to his gamut of styles. Yet at least we find him still doing what he loves best at the end of a show that offers some pretty ordinary stuff as well as some great stuff, but overall keeps us looking and keeps us intrigued, in that way Hockney has found it so easy to do over a career of seven decades.

David Hockney – Drawing from Life is at the National Portrait Gallery, until 21 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks