The infinite appeal of Yayoi Kusama, the artist who checked into a psychiatric hospital in 1977 and never left

People queue for hours to spend one minute in Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms. Her stock in the art market is high too. But how to explain the nonagenarian artist’s stratospheric success? Alastair Smart looks at the Japanese artist’s enduring popularity

In November 1968, a few months shy of her 40th birthday, the artist Yayoi Kusama sent an open letter to the then President-elect of the United States, Richard Nixon. She offered to have sex with him – to “lovingly, soothingly, adorn [his] hard masculine body” – if he agreed to end US involvement in the Vietnam War.

It is not entirely clear whether she was serious, or whether Nixon replied. What’s undeniable, though – not to mention remarkable – is that more than half a century later, aged 94, Kusama is still creating a stir.

Her work, typically featuring striking patterns of polka dots, seems to be everywhere this year. A show of inflatable sculptures, Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons, is the inaugural exhibition at Manchester’s £211 million new arts centre, Aviva Studios. Her pair of Infinity Mirror Room installations are still wowing visitors at Tate Modern. (They opened in 2021 and, due to popular demand, keep having their closing date postponed – currently it’s April 2024). Further afield, a major career retrospective, Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now, has just opened at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Her impact isn’t restricted to the art world either. In January, Kusama launched a mega collaboration with fashion house, Louis Vuitton. For this, she deployed her signature polka dots in the design of myriad handbags, trainers and other items – as well as the decoration of Louis Vuitton shopfronts and interiors worldwide. (An animatronic robot version of Kusama could even be seen painting dots in window displays in London, Paris and New York.)

The market for her art isn’t shabby either. In 2014, Kusama’s 1960 painting White No.28 fetched $7.1m at Christie’s in New York, then the highest price ever paid for a work by a living female artist at auction.

How to explain the stratospheric success, though, of a nonagenarian who checked herself into a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo in 1977 and never checked out?

According to Glenn Scott Wright, the director of London’s Victoria Miro gallery, which represents Kusama in Europe, part of the explanation is that the art world is “correcting” itself. Earlier in her career, “she was doubly an outsider – both a woman and Japanese – and wasn’t recognised in the way that white male artists were”. Nowadays, with the art world striving to become a more egalitarian place, “there’s a better understanding of her importance”, Wright says.

Another factor, surely, is Kusama’s back story. She has suffered with mental illness her entire life, and – as exemplified by Vincent van Gogh, albeit posthumously – public knowledge of this can burnish an artist’s reputation. Understanding of mental illness has increased significantly since the Dutchman’s day, of course, but there abides a belief that suffering transmutes somehow into heights of artistic expression.

Some of Kusama’s own comments are interesting in this regard. “I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I’ve found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art,” she wrote in her autobiography, Infinity Net, in 2011.

To fully understand Kusama’s place in contemporary culture, though, one needs to look back at her early life and career. She was born in the city of Matsumoto in central Japan in 1929, into a comfortably-off family who ran a plant nursery. It wasn’t a happy childhood. Her father spent much of it philandering, while her mother – vehemently opposed to Yayoi’s dreams of becoming an artist – used to rip up her pictures routinely. The youngster also experienced frequent hallucinations, often involving flowers talking to her.

Kusama attended art school after the Second World War, but found Japanese society too conservative. In the mid-1950s, she moved to the US. Initially, she lived in abject poverty, surviving on fish heads scavenged from a New York fishmonger’s rubbish, which she boiled for soup.

In time, however, she achieved success with a series of abstract paintings known as the Infinity Nets, of which the aforementioned White No. 28 is an example. These consist of large canvases covered in tiny, repetitive loops that create a mesh – or net – effect overall.

Kusama was now showing work alongside Andy Warhol, being championed by Georgia O’Keeffe, and dating Donald Judd – not a bad trio of artistic associates.

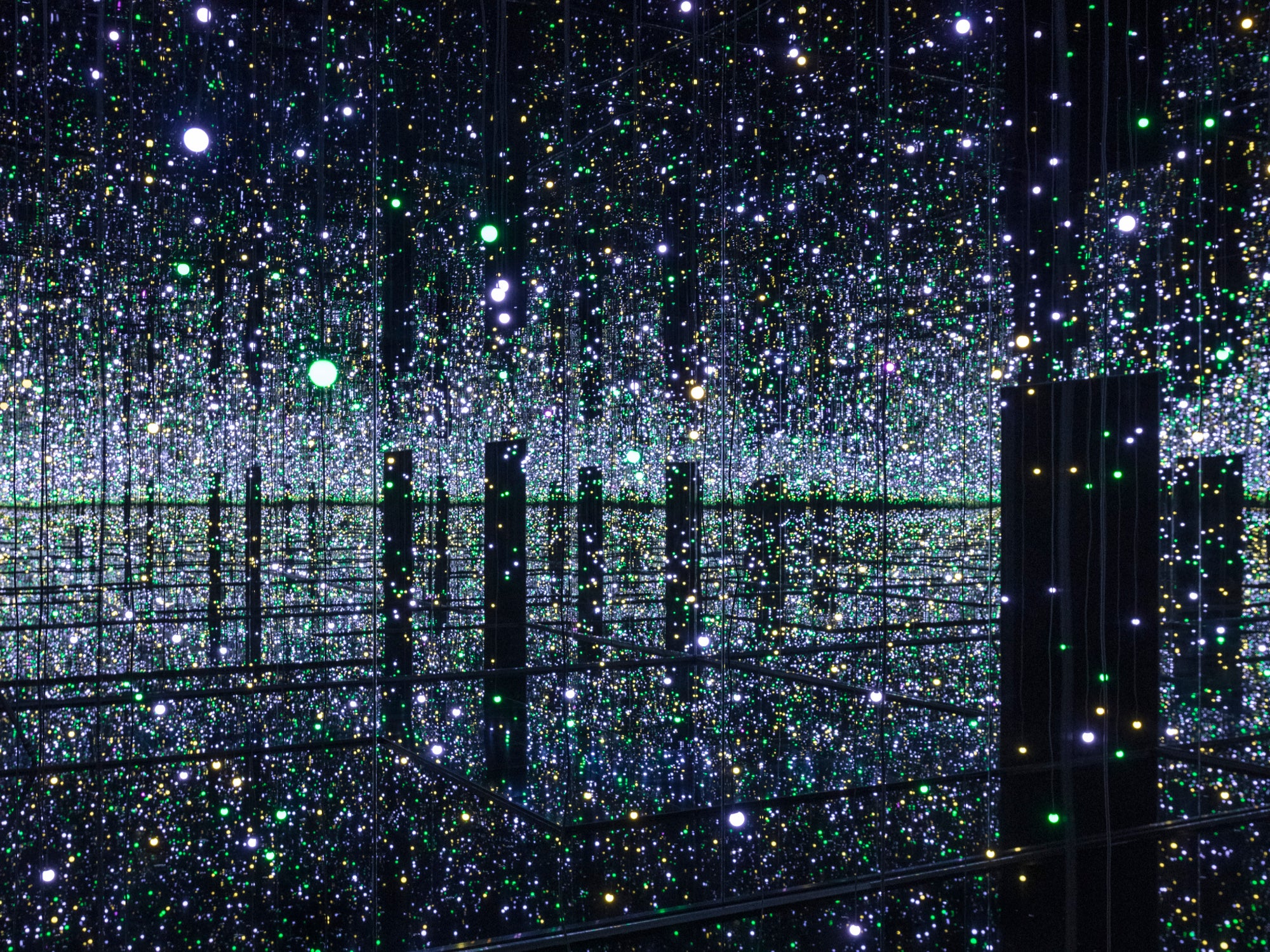

In 1965, she made her first Infinity Mirror Room, more than 20 of which exist today (including the two on view at Tate Modern). These have been fundamental to her recent success and comprise rooms covered entirely in mirrors, which become chambers of infinite reflection.

To step inside one has always been an immersive experience – though 21st-century examples are higher-tech than those of old, typically featuring some very trippy LED light effects. (Today, Infinity Mirror Rooms pop up regularly at galleries and museums worldwide, with queues often exceeding three hours for a session inside often limited to just a minute.)

By the late 1960s, Kusama was orchestrating a series of naked happenings around New York. These tended to feature dancers, painted from top to toe in polka dots, campaigning for political causes such as an end to Wall Street hegemony and US involvement in Vietnam.

In 1973, following a media backlash against her happenings, Kusama returned to Japan. Before long, she began to suffer from exhaustion and her mental health deteriorated. Her life since 1977 has been spent between Seiwa Hospital and her studio nearby. She continues to work to this day, supported by a small team of assistants.

“She takes nothing for granted,” says Wright, who goes to visit Kusama three or four times a year. “She’s very appreciative of the attention that has come her way late in life.” Wright believes that it has been “around 12 years” since the artist’s fame really took off, citing her major touring retrospective – held at Madrid’s Reina Sofia museum, Paris’s Centre Pompidou, London’s Tate Modern, and New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art in 2011-12 – as a key moment.

This may well be true in terms of curatorial and institutional recognition. Here, at last, was a proper exposition of the place that Kusama had occupied in several important movements of the second half of the 20th century: from Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism to performance art.

In terms of popular appeal, however, a more important date from around the same time was October 2010: the launch of Instagram. Kusama’s eye-catching art – the Infinity Mirror Rooms, in particular – provides the perfect backdrop for a selfie, with its mix of gleaming lights and patterns of vibrant colour. Adele and Katy Perry are among the 100,000 users who have so far posted #infinityroom selfies on Instagram.

Connected to this, there has been a growing trend in recent years for art of a more experiential type. Gallery-goers are increasingly used to coming across more than just oil on canvas. Even past masters such as Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo and Salvador Dalí have had their work adapted for immersive experiences – that is, digitally reproduced as giant projections across a venue’s walls, ceiling and floor. The Infinity Mirror Rooms fit this trend perfectly.

Doryun Chong, the co-curator of Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now, adds that the Covid pandemic may also have boosted the Japanese artist’s renown. “That period exposed the precariousness of human existence, and I think encounters with Kusama’s art since have renewed our belief in the power of art to heal,” Chong says. “Her work has something embedded in it that nourishes the soul."

There remain several questions and paradoxes about Kusama’s career. For one thing, how actively involved is she nowadays in the myriad decisions made regarding what art she shows where? Also: how has imagery rooted in mental anguish ended up generating so much joy across the globe?

Whatever the answers, Kusama is enjoying a moment where, for slightly different reasons, her appeal to both the public and the art establishment is simultaneously sky-high. To some extent, that has been fortuitous and the result of societal and cultural changes that she could never have foreseen. However, if you’re a risk-taking creative who works into your nineties, you’re giving yourself a fair chance of being around to see the world catch up with your ideas.

‘Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons‘ is at Aviva Studios, Manchester, to 28 August

‘Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Rooms’ is at Tate Modern to 28 April 2024

‘Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now‘ is at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao to 8 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks