Michael Craig-Martin’s magical secret to being a great artist – and how he inspired a generation of YBAs

Ahead of a career retrospective at the Royal Academy, the Irish-American conceptual artist tells Mark Hudson about finding fame in his fifties, about the importance of Catholicism on his work and what he taught a generation of Young British Artists

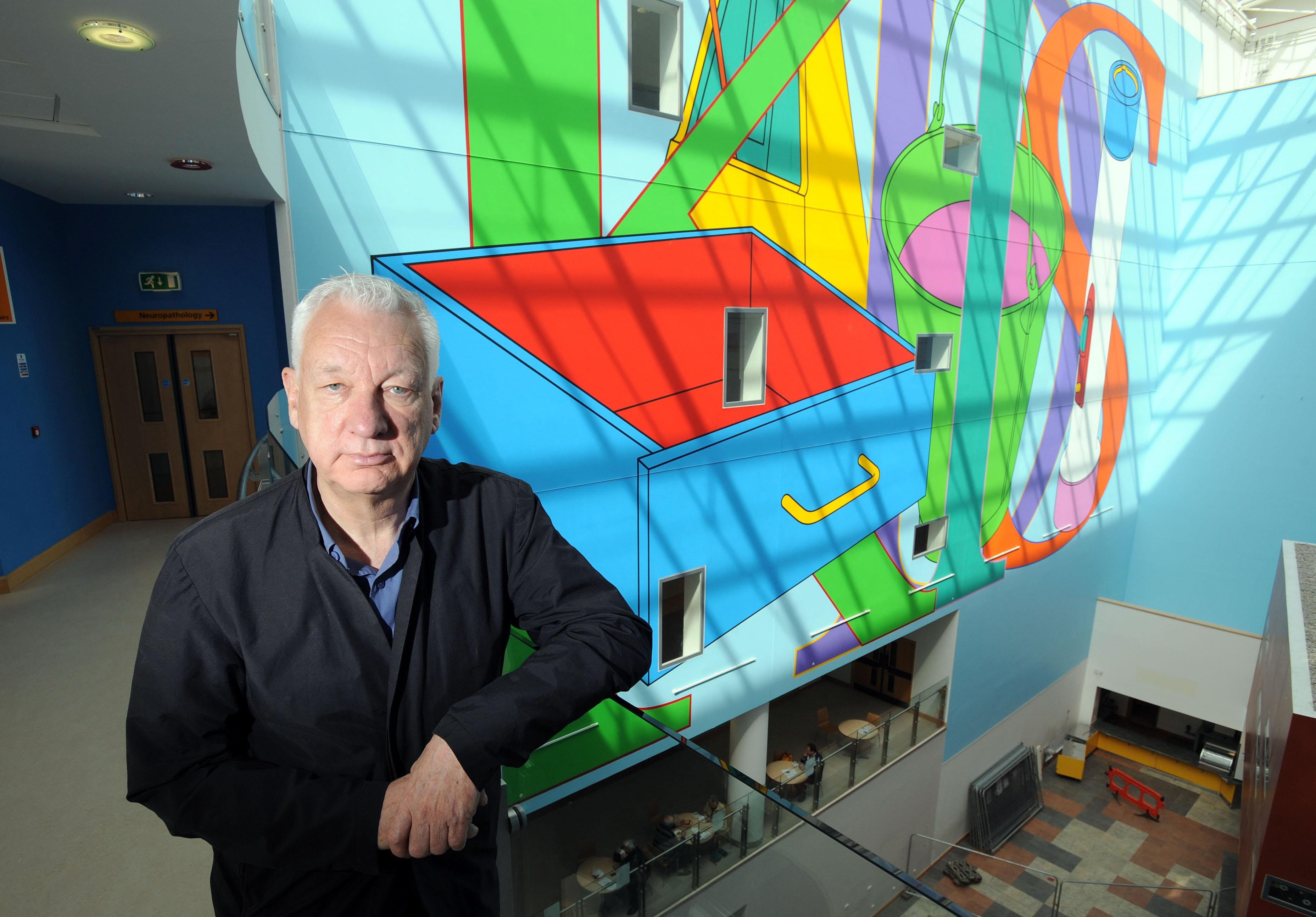

Michael Craig-Martin looks out from his 21st-storey apartment in the Barbican, the immense London sprawl spread out before him. The urbane Irish-American artist has played many roles since arriving here in 1966: pranksterish conceptual artist in the Seventies, guru to the YBA generation in the Eighties, and creator, more recently, of a kind of digital-age still life painting in eye-popping colour. Yet it’s only now that he’s getting his due as one of the handful of living artists to have been accorded the honour of a retrospective exhibition in the Royal Academy’s palatial main galleries. Does he feel he’s finally got the British capital at his feet – in all senses?

“I’m 83 tomorrow,” he says in a tone of wonder. “And it’s as though everything I’ve ever worked on or thought about is coming together now.”

For all his presence on the London art scene over nearly half a century, from youthful interloper to distinguished elder statesman – a Royal Academician indeed – Craig-Martin was a late developer in terms of creating an immediately identifiable style. Indeed, he didn’t even start making the paintings for which he is best known until the mid-Nineties, when he was well into his fifties.

“Most artists have their career high point early or in mid-career, and when they have a big retrospective it’s giving recognition to work produced over a long period,” he says. “So it’s interesting to me that my career high is coming now, with an exhibition of work mostly produced very recently, if not right now.”

There are interviews that feel daunting because the subject has a reputation for being surly, incoherent or simply shy. But on the evidence of Craig-Martin’s formidably articulate autobiography-cum-how to book On Being an Artist, the more unnerving certainty is that there is likely no question to which he won’t have a clearly thought out and long practised answer.

Yet I feel on friendly terms with the genial, sharp eyed Craig-Martin from the moment he answers the door: it’s no wonder he’s been so effective as a teacher. And everything in his supremely tasteful living space clearly relates to his work, from an abstract print by the great Bauhaus master Josef Albers, one of his key influences, to pieces of classic modernist furniture (including a spectacular curved sofa in turquoise leather and stainless steel), every one of which has featured in his paintings or prints.

“The basis of my life is my work and I approach everything in exactly the same way that I approach my art, whether it’s teaching, curating an exhibition or furnishing my apartment.” He glances around with a faintly apologetic shrug. “It’s been useful, because whatever I’m confronted with I have a way of dealing with it.”

A good example is the vast immersive digital installation that will form one of the centrepieces of his Royal Academy exhibition. “The curators told me they wanted to include something like this, a kind of project I’d never attempted before. But I had a brainstorm, and I thought: what if I use every image I’ve ever drawn? So I gave 300 images to a digital technician I work with and we’ve been working on it for the past year.”

Born the son of an agricultural economist in Dublin in 1941, Craig-Martin was raised largely in Washington DC, with a Roman Catholic education. The influence of this on his life was sometimes pernicious: although he married a fellow Yale student in 1963, with whom he had a daughter, Jessica, he only felt able to come out as gay 13 years later, unable to live a lie that had been forced on him, he felt, by the dogmas of his Catholic background. Yet that background also gave him an alertness to the symbolism behind everyday objects – it was indeed a priest who alerted him to the possibility of becoming an artist. While studying fine art at Yale, he took classes that had been devised by Albers, who had fled Germany for the US in 1932, and were now taught by his former students, giving Craig-Martin’s work a direct link to the great days of European Modernism, of which he remains extremely proud. The results of these classes were very small abstract sculptures. He didn’t then have the confidence to think of himself as a painter.

At the same time, Yale’s proximity to New York allowed him to see the first exhibitions of Pop Art, conceptual art and minimalism, at a moment when American art’s confidence was at an absolute peak.

Yet on graduating from Yale in 1966 he took a job teaching at Bath Academy of Art, located in the countryside just outside that quintessentially English historic town then still in a state of post-war shabbiness. I suggest to him that it’s intriguing he chose to exchange the dynamism of a society with an “instinctive optimism” for the dingy and limited confines of a society with an “instinctive pessimism” – Britain.

“I thought of myself as American. But I was aware my roots were in Europe. Even today I feel surprisingly Irish considering I have never lived there. So when I got the chance of a job at a British art school, with the opportunity to find out what life here would be like, I jumped at it.”

What started as a kind of belated gap year became, essentially, his life. He has lived in London ever since. Clearly there is something about living in the UK that he likes. “Students here are expected to be independent minded and take responsibility for their own trajectory much earlier than they are in America. That impacts on the sciences and the arts, the creative areas where this society is really powerful. At the same time there’s a kind of extreme provincialism and natural conservatism in British society.”

Can he give an example of the latter? “We’ve just had 15 years of it in government.”

His first significant success came in 1974 with An Oak Tree, a seminal piece of British conceptual art, in which a glass of water placed on a high shelf was declared to be an oak tree, with an accompanying text talking through the ramifications in Q&A form. First exhibited in the relatively small Rowan Gallery it quickly became one of the most talked about artworks in London. If it sounds like a cross between Marcel Duchamp and Monty Python, the work’s roots he says are in the Catholic idea of transubstantiation, that an object can change its identity through the belief of the beholder, as the communion bread does in the Catholic Mass.

At the same time he admits that he feels concerned if he doesn’t quickly get laughs when he reads this text to audiences today. A note of deadpan drollness runs through all his work, from his early conceptual pieces to the pun-laden dialogues between flatness and three-dimensionality in his current paintings. “As a way of talking about very complex things in language that anyone can understand, and which undermines pomposity and mystification, humour is really a no brainer.” I put it to him that his contribution to the YBA movement, many of whose key members he tutored at London’s Goldsmiths College in the 1980s, including Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas, was to give these feisty young artists permission to manipulate the structures of the art world using the language and imagery of their own generation and social background.

“Well, I think I’m very good at giving people permission generally. As a teacher, I’ve never had a message, something I want to tell the students, just as I don’t have that in my art. My tactic has always been to encourage them to address their own core interests which they often don’t recognise. People can be blind to their central selves. So I’d always start by asking them as much as possible about themselves on a very basic level: how many brothers and sisters they have, what books they’ve read.” One striking example was the Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Wallinger, an MA student at Goldsmiths in the early Eighties, who recalls a visit Craig-Martin once made to his bedsit studio as a life-changing experience. “There were no studios for MA students”, he told me in a recent interview, “so the tutors came to where you were.” Wallinger’s cramped living space was crowded with dour figurative paintings inspired by the then fashionable neo-expressionism. “Michael was there for three hours, and we spent the entire time roaring with laughter. As he left he said, ‘Well we’ve had some laughs, but there aren’t many laughs in your work.’ I was dumbfounded. It had never occurred to me that art could be funny, or at least that my art could be funny.”

Yet Craig-Martin came to regard his close association with the YBAs as a liability. “I felt a parental pride in their success, and it brought me more international recognition than I’d had through my own work. But I hated being thought of as primarily a teacher, and that became an incentive to prove that that idea of me was wrong.”

He did that by heading into an area he’d always regarded with scepticism – painting – and a thing of which he’s always been frankly scared – colour. He confronted the latter fear by using colour at its most intense: “the reddest reds and bluest blues”.

If Craig-Martin’s failure to build on his Seventies success with An Oak Tree – to create a “body of work” around that seminal piece – had frustrated him at the time, it proved a retrospective blessing as his name and reputation weren’t fixed in a particular historical era. He was able to have a breakthrough moment at the age of 55, some time after his famous students had made their reputations, with deadpan studies in everyday materiality, with clocks, salt pots, musical instruments, for example, captured in simplified outlines and brilliant staccato colour; works that still feel highly contemporary.

While he remains “indifferent to the status, function or value” of the objects he portrays, increasingly they are things associated more with teenagers than with octogenarians: bags of fries, headphones, trainers. “The momentum of change is being driven by the young today in ways that seem natural and obvious to them, but feel unsettling to everyone else.”

In his book On Being an Artist, Craig-Martin scoffs at the idea of artists “reinventing themselves”. Which feels rich coming from an artist who might be said to have done precisely that, at least twice. Is there a chance he might still surprise us all again, thirty years after his last major breakthrough?

“Well,” he says with a gentle shrug. “I have no plans to retire.”

Michael Craig-Martin is at The Royal Academy from 21 September to 10 December. royalacademy.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments