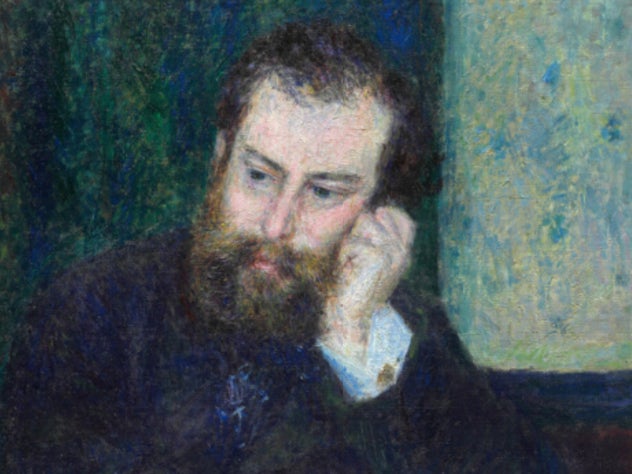

Was Alfred Sisley’s Britishness the reason he wasn’t always given credit as a great Impressionist master?

As a new exhibition opens in Paris to mark 150 years since the birth of Impressionism, Alastair Smart considers why Alfred Sisley, the talented peer of Monet and Renoir, has often been lost from the story of the most influential movement in art history

Shortly before Alfred Sisley died, in January 1899, Claude Monet labelled him “as great a master as any who has ever lived”. High praise – albeit not shared by posterity.

One of six artists who comprised the core of Impressionism (Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro and Berthe Morisot being the others), Sisley is largely forgotten today. Certainly by comparison with his peers.

At his best, his works – landscapes typically – reveal wondrous plays of light and atmospheric effects. Not to mention exquisite brushwork and a harmonious use of colour.

The first Impressionist exhibition opened in Paris on 15 April 1874, meaning this year marks the 150th anniversary of art’s most beloved movement. It seems an apt moment to explore, and hopefully explain, Sisley’s fate.

“He doesn’t get the attention he deserves,” says Anne Robbins, the co-curator of Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism, a new exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay focusing on the birth of the eponymous movement. “Back in 1874, he was a key figure… one who commanded attention.”

Sisley, along with Monet and Pissarro, was one of three artists who helped coin the very term “Impressionism”. The critic Louis Leroy came up with it, feeling that their paintings had been so rapidly executed that they created only an impression of a given scene – rather than a precise representation of it.

This year also marks the 125th anniversary of Sisley’s death. However, not a single activity is being held in his honour. (Unless you count the charming Sur les pas de Sisley walking tour, which visits key spots the artist painted in Moret-sur-Loing, the small town southeast of Paris where he spent his final two decades. That has been going for a few years, though, and isn’t new for 2024.)

Neglect of Sisley is perhaps all the more surprising in this country, given he was a British citizen all his life. Robbins suggests it’s partly because “he died earlier than his peers” – from throat cancer, aged 59. Renoir and Pissarro lived into their seventies; Degas and Monet into their eighties. “By having a career that didn’t extend into the 20th century, perhaps he’s perceived as less modern than the others.”

Before drawing further conclusions, let’s look back at Sisley’s career. He was born in Paris in 1839 to expatriate British parents. As a young man, they sent him to London to study commerce, hoping he would join his father’s successful textile business. He spent most of his time there, though, visiting the National Gallery (its Constables likely helped inspire a fascination with the sky in his own paintings years later).

Resolved to become an artist, he joined the atelier of Charles Gleyre, once back in Paris in 1862. Here, he befriended a number of painters his own age – Monet and Renoir, most notably – with whom he made regular trips to spots such as the forest of Fontainebleau to paint landscapes en plein air. (Their novel practice of painting entire pictures outdoors would become a tenet of Impressionism.)

Sisley’s best decade, artistically, was the 1870s, a time when his work combined all the qualities mentioned above, as well as a mastery of composition. This frequently involved a river, path or country road that curves into the distance, enticing viewers to follow its course. A fine example is The Route from Saint-Germain to Marly (currently on view in the Paris 1874 exhibition), one of five paintings he contributed to the first Impressionist show.

At Sisley’s funeral, the art critic, Adolphe Tavernier, called him “one of the most remarkable landscapists” of the 19th century. His brushstrokes might be flecked in one part of a picture and thick in another, varying according to what he was depicting, but the visual effect overall was balanced and even.

Sisley stuck broadly to an Impressionist approach till the end of his life. “This is a key area in which his reputation has suffered,” says MaryAnne Stevens, who curated the artist’s first-ever big retrospective, an internationally touring show that came to London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1992.

“In the 1880s, when the other Impressionists started evolving their style and moving on from the movement, Sisley never really did. This has been interpreted by many as showing repetition and a lack of ambition.”

The same has been said of his decision to devote his career almost exclusively to landscapes. Part of what made the Impressionists so radical was their depiction of scenes of modern life as it was being lived in and around Paris – witness the revellers dancing their Sunday afternoon away in Renoir’s Bal du moulin de la Galette, or the passengers in Monet’s pictures of Saint-Lazare train station.

Sisley’s natural habitat, by contrast, was the tranquillity of the Île-de-France: in rural or semi-rural spots outside Paris such as Louveciennes, Marly-le-Roi, and Moret-sur-Loing. Figures do appear in his work, but they tend to be small and anonymous, meant only to give scale to a landscape – such as the solitary figure in Snow at Louveciennes. (Few artists in history have painted snow more beautifully than Sisley.)

It’s worth noting that the art establishment rejected him in life, just as they have done in death. After his father’s business collapsed following the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1, Sisley struggled to make ends meet – with a partner and two children to support.

His surviving letters reveal a constant search for collectors and cash. “I’ve always had to worry about how to get my work known, and in most cases failed”, he wrote in 1890. It’s true none of the Impressionists succeeded initially – their work was too progressive for most tastes. However, by the 1890s, Monet and Renoir in particular were making good money.

Part of what makes Sisley’s art so interesting is that it has a serenity belying the difficult circumstances in which it was made. His latter years were increasingly spent caring for his cancer-stricken partner, Eugénie, and battling the same disease himself.

After three decades together, the couple finally decided to marry during a trip to Wales in 1897. Sisley would paint a group of pictures there of Storr’s Rock, a vast outcrop in Langland Bay on the Gower Peninsula. On some level, he doubtless saw this storm-tossed boulder as a symbol of his and Eugénie’s enduring love. (She would die in October 1898, and he a few months later.)

Arguably the finest Storr’s Rock picture is on view at National Museum Cardiff, one of a smattering of Sisley works in UK public collections. According to their respective websites, Tate and the National Gallery own a combined total of five paintings by him, only one of which is on display.

What of Sisley’s Britishness, in fact? Was it detrimental to his career – and indeed legacy – to have been the only non-French person among the founding Impressionists?

“I don’t think so,” says Stevens. “There’s no record of his ever being treated as an outsider or foreigner. He lived almost all of his life in France and was considered French. On a purely artistic level, the Impressionists as a group – not just Sisley – owed an indirect debt to Constable, who had made a famed contribution to the Paris Salon exhibition of 1824 and [whose loosely brushed scenes] had influenced France’s Barbizon school of painters, out of which Impressionism emerged. Sisley was no more ‘British’ than his peers in that respect.”

So where does this leave us? With an artist of narrow range, in terms of genre and style, but whose work within that range was often gorgeous. Surely it’s time to make some noise for the quiet man of Impressionism.

Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism is on at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, until 14 July, and features a number of works by Sisley. For deals on train travel to Paris and exhibition entry, visit eurostar.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks