Inspired by Greece, forgotten by Britain: why maverick painter John Craxton deserves his moment in the sun

He was flatmates with Lucian Freud before they later fell out, and he was largely forgotten when he moved from London to Crete in 1960. An exhibition at Pallant House Gallery gives artist John Craxton his due but, writes Alastair Smart, was he forgotten for not suffering enough for his art?

The centenary of John Craxton’s birth, in 2022, wasn’t marked by a single exhibition of note in his native land. If this seems unjust, it was also in keeping with the London-born artist’s reputation from the moment he settled in Crete in 1960. Thereafter, he was to a large extent ignored by the powers-that-be in the British art scene.

Partly, this was a simple case of “out of sight, out of mind”. Craxton had had a successful start to his career, but in the late 1960s was dropped by his London dealers, Leicester Galleries. Not that the artist – who was living his best life, knocking back ouzo and basking in Greek sunlight – seemed to mind. Yes, he continued to work, but it was very much at his own speed. “I work best in an atmosphere where life is considered more important than art,” he said.

Craxton died in 2009, aged 87. His friend Ian Collins published a fine biography called John Craxton: A Life of Gifts two years ago, and has followed that up by curating the biggest exhibition of the artist’s work in decades, which recently opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. Visitors can now make up their own minds about Craxton’s standing in the pantheon of British artists. The sale of the painting, Summer Triptych, for £343,000 at Bonhams this summer – the highest price ever paid for a work by Craxton at auction – suggests that his reputation may be on the up.

He was born in October 1922 into a cultivated family in St John’s Wood, the fourth of six children by Harold Craxton (a professor of pianoforte at the Royal College of Music) and Essie Faulkner (a violinist). They encouraged young John’s fondness for art.

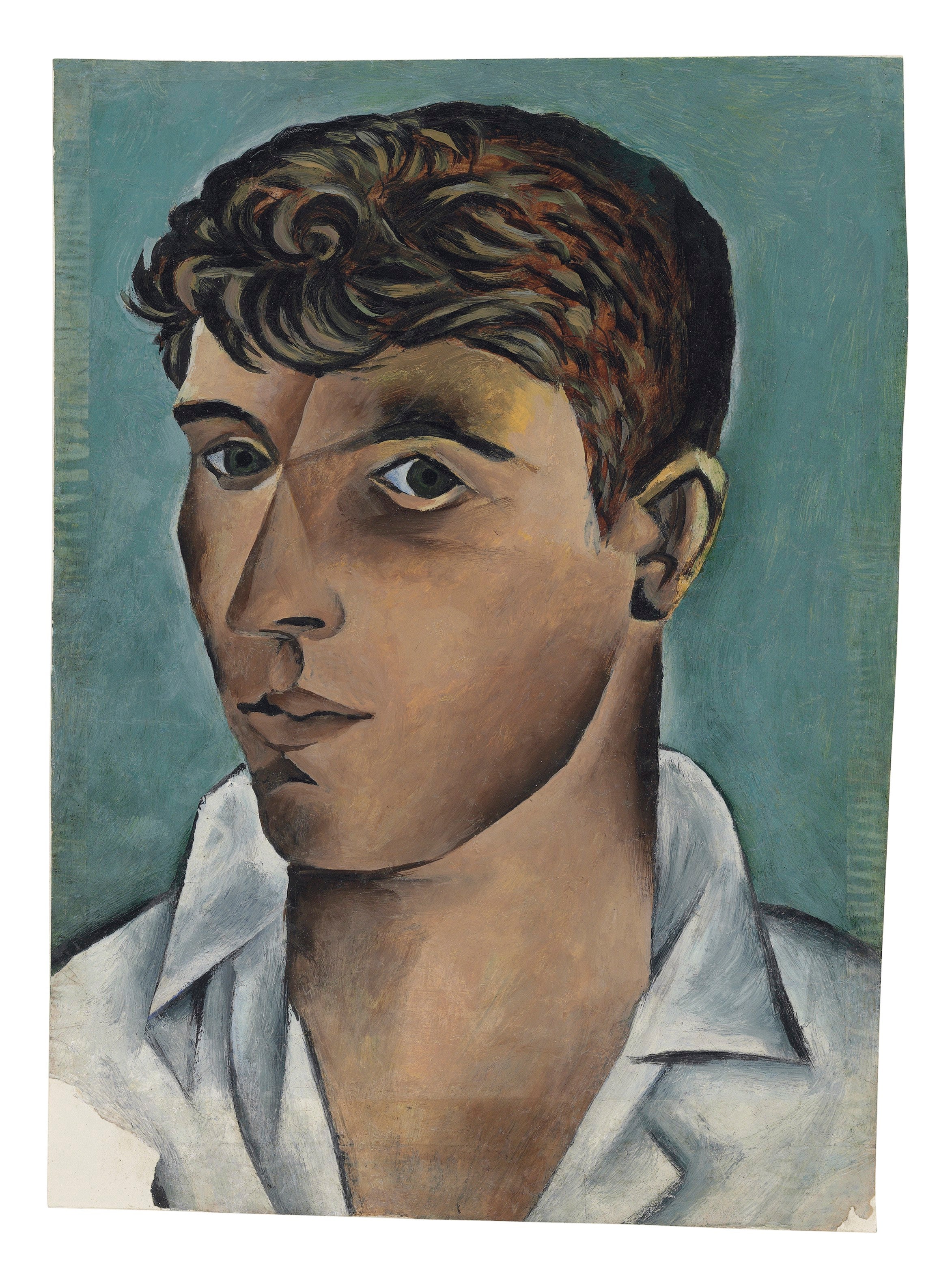

Aged 16, he moved to Paris, where he studied life drawing at L’Academie de la Grande Chaumière. The onset of the Second World War, however, forced his return to London. In 1941, at around the same time that he failed an army medical due to tuberculosis, he had the good fortune of meeting Peter Watson, the proprietor of the leading cultural magazine, Horizon. Watson saw enough potential in Craxton’s work – and that of his peer, Lucian Freud – to put the pair up in a flat together, purchase a number of their works, and introduce them to establishment figures. (When Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery, popped over to visit one day, Craxton and Freud – at that stage, keen painters of dead animals – had to hide the putrid corpse of a monkey in their oven.)

Watson also introduced Craxton to Graham Sutherland, who became a mentor. Through trips to Pembrokeshire together, the former adopted the latter’s view that landscape painting should be about more than just replicating nature. It required invention too, in poetic or emotional response to one’s surroundings. With works such as Reaper with Mushroom – which depicts a lonely youth in an eerie landscape, a sickle in one hand and a freshly cut mushroom in the other – Craxton came to be labelled a Neo-romantic.

In the spring of 1944, his debut solo show, at Leicester Galleries, sold out. When the War ended, Craxton longed to escape British shores for Greece, where Watson told him he would find scenery of endless inspiration. An opportunity came in May 1946, at the vernissage of an exhibition of his in Zurich. There he met the wife of the British ambassador to Athens, who happened to be in town buying curtains and offered Craxton transit to Greece on her plane.

The artist immediately took to his new milieu, touring numerous islands before finding a favourite in Crete. According to Collins, “from now on, until his death, almost every picture he produced paid tribute to the light, life and landscapes of the Aegean. His personal and artistic trajectory was a voyage from blackout into brilliance, from a cold island to a liberated life in the sun.” (Initially, Craxton split his time between Crete and London, though he moved permanently to the town of Chania in the former in 1960. Part of the liberation referenced by Collins came in the form of a constant supply of sailors, whom the gay artist encountered at nearby Souda Bay.)

The images he had made in rain-sodden wartime England – typically, monochrome scenes, featuring melancholic shepherds and poets under troubled skies – now gave way to hedonistic pictures altogether brighter in mood and colour. These included Three Dancers, Poros (1953-54) and myriad other examples of exuberant figures dancing. What’s more, where the shepherds of old had been imaginary, he now took to depicting real-life examples he saw tending their flocks – such as the subject of Greek Farm (1946). Real-life sailors, fishermen, cats and goats were also portrayed regularly. Craxton left the sombre English Neo-romanticism of Sutherland, Paul Nash, John Piper and others behind, and never returned to it.

As early as 1948, he recognised London as a place where he felt “squashed flat”. In Crete, mixing with people from all echelons of society, he would dine with Sir Winston Churchill on Aristotle Onassis’s yacht one night, then hang out drinking with locals in a ramshackle taverna the next.

The Sunday Times’s art critic, John Russell, said the paintings suffered from “the handicap of happiness”

He counted among his friends the writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, a fellow Englishman in Greece, almost all of whose book covers Craxton illustrated. Pastimes included riding his Triumph motorbike across his adopted island – something he did till the age of 80 – and indulging in long lunches. When speaking at Craxton’s memorial service at St James’s Piccadilly in 2010, his friend David Attenborough said “One of my great pleasures was to be taken by John to his favourite harbourside restaurant in Chania and be given a dish of boiled sea creatures which even I, who am supposed to have some knowledge of the animal kingdom, found hard to identify”.

One rare source of discord in the artist’s life was his relationship with Freud, which soured dramatically from the late 1970s onwards. It was damaged by, among other things, a dispute over the attribution of some early drawings, and culminated in a gravely ill Craxton telling his doctor: “It’s essential that I outlive Lucian.” (He didn’t quite manage it, Freud surviving him by two years.)

As for his art, Craxton’s mature style consisted of a blend of influences – from El Greco, Miró and Cubism to Byzantine mosaics and the aforementioned Mediterranean colour and light. It also boasted a linear energy that was distinctly his own. In 1967, Craxton had a retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and it’s worth dwelling on one particular review of it – that by The Sunday Times’s art critic, John Russell, who said the paintings suffered from “the handicap of happiness”.

Russell’s point was that the artist had retreated into some kind of sunlit lyricism. It also suggests a reason for Craxton’s relative lack of recognition today – namely, the abiding trope that artists should suffer for their art; that, in the longstanding tradition of Vincent van Gogh, Francis Bacon, Frida Kahlo and others, artists should make sacrifices (mental, physical, emotional and/or financial) for their creativity.

In Craxton’s case, that notion was all Greek to him.

‘John Craxton: A Modern Odyssey’ is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, to 21 April 2024; pallant.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks