The extraordinary inside story of the $100m Andy Warhol Foundation fraud that shook the art world

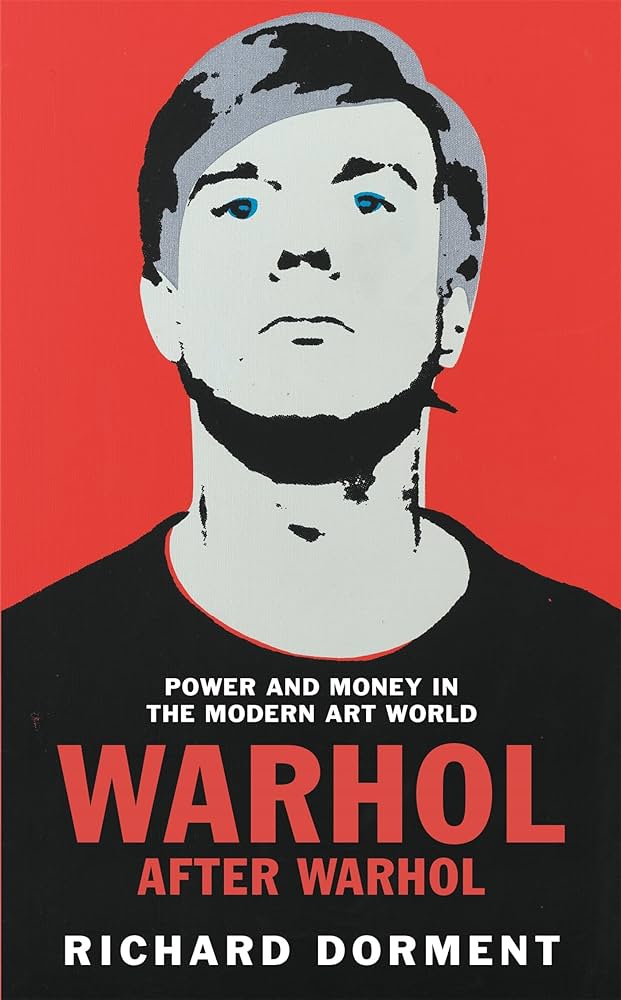

Part detective story, part art history, part gripping courtroom drama, art critic Richard Dorment’s new book, ‘Warhol after Warhol’, tells the spellbinding tale of corruption and lies surrounding the most famous American artist of the twentieth century

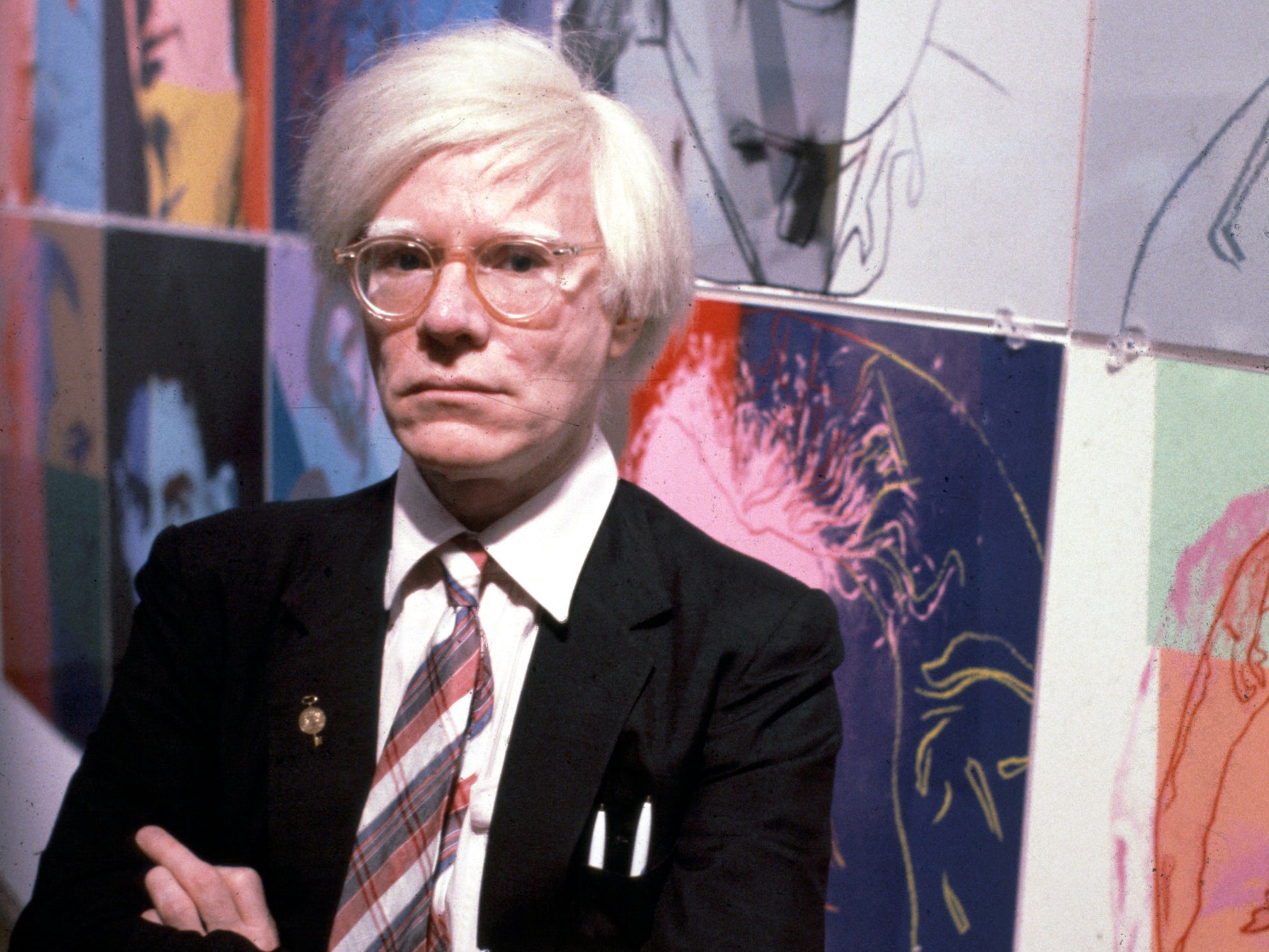

This excerpt documents the bombshell moment when, through his lawyer Brian Kerr, Joe Simon uncovered the scale and scope of criminal wrongdoing by the Andy Warhol Foundation and Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board. My initial investigation focused narrowly on whether Warhol’s 1965 series of Red Self-Portraits were authentic, as Simon, who owns one of the paintings believed, or worthless ripoffs that had nothing to do with Warhol.

Early on, he had been warned by the Warhol Foundation’s sales agent, Vincent Fremont not to mount a legal challenge to the Board’s decision to deny the authenticity of his painting. “Don’t even think about it. They’ll drag you through the courts until you bleed. They never lose,” Fremont had told him.

It is typical of Simon that he ploughed ahead anyway, armed only with the absolute certainty that he was doing the right thing. This excerpt takes place during the pre-trial hearings. Simon’s lawyer is cross–questioning employees of the Warhol Authentication Board and the Warhol Foundation. Simon is sitting right behind his attorney, passing him yellow Post-it notes, telling him what to say next.

And then he goes off-piste, ignoring the Red Self-Portraits in order to put new information about the Warhol Foundation on the record. He has found documentary evidence that, in flagrant abuse of the values it professed to hold, the Foundation had confiscated paintings from the offsite factory where many of Warhol’s works were made, on the grounds that they were fake, then sent them to their own authentication board to stage a sham “investigation”, guaranteed to declare them to be, after all, genuine Warhols, many of which were sold for millions of dollars.

Good looking, talented and amoral, Rupert Jasen Smith cheated Warhol and other artists by creating and selling unauthorised prints of their work on an industrial scale...

Brian Kerr’s interrogation of the dealer Vincent Fremont on 7 July 2010 was more focused than usual, in the sense that he mainly questioned the witness about a group of 44 paintings which the estate of Andy Warhol had seized from their original owner on the grounds that they were forgeries. Primed with incriminating information he had found during the discovery process, Kerr never asked Fremont a question to which he did not already know the answer. Because of the specific nature of Kerr’s questioning, Fremont realised – or suspected – as much. He was on his guard, but also under oath. If he perjured himself and the case was to go to trial, a lie would be exposed. Would Fremont risk that, or would he tell the truth? To understand what happened in the next few minutes, we must go back in time to 25 September 1991, when Fremont, on behalf of the Warhol estate, wrote to Rupert Jasen Smith’s executor, Fred Dorfman, and his heir, Mark Smith.

Fremont’s letter demanded that they hand over 44 designated paintings from Smith’s studio. A fine-art printer of genius, Jasen Smith’s gift as a colourist far surpassed that of any painter of the period. Good looking, talented and amoral, he cheated Warhol and other artists by creating and selling unauthorised prints of their work (In his offsite studio) on an industrial scale. Whether this group of forty-four paintings had been made during Warhol’s lifetime or after his death in 1987 is not known. But, when Smith died in 1989, they had become part of the printer’s estate. Fremont seized the pictures on behalf of the Foundation because they were ‘not the work of Andy Warhol’, and, as his letter went on to say:

... because of the similarity of the paintings to authentic works by Andy Warhol, their release might threaten the integrity of the art market and Andy Warhol’s reputation. Accordingly, the Warhol Estate has requested that you relinquish any right, title or interest you may have in the paintings and assign the same to the Warhol Estate... by signing this letter you confirm said agreement, release and assignment. We appreciate your cooperation in this matter.

As requested, Dorfman personally turned the pictures over to the Warhol estate, without asking for or receiving compensation. In his letter, Fremont wrote: “the Warhol Estate came to the opinion that the paintings are not the work of Andy Warhol, and, as provided in the letter of agreement, a legend to this effect has been endorsed on the reverse side of each canvas”. In plain language, the confiscated works had been stamped with the word DENIED to reflect the estate’s judgement that they were fakes.

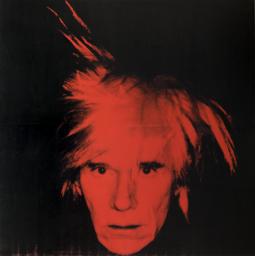

But there was a catch. The Warhol estate’s stamp was entirely different from the one later used by the Authentication Board to stamp Simon’s painting. The crucial difference is that works such as Simon’s painting were impressed with indelible red ink. Works owned by the Foundation, on the other hand, were lightly stamped Warhol Estate using soluble ink, which could be easily removed with water if, for example, the Board changed its mind or if for any other reason the Foundation decided to sell these works as genuine. In the Foundation’s own words, the stamp could be made to disappear “if circumstances warrant”. The 44 works in question were paintings on canvas, including such famous images as Warhol’s 1986 Fright Wig self-portrait, a large-scale example of which Sotheby’s sold on behalf of the designer Tom Ford, in May 2010, for over $32m.

All this Kerr knew. His purpose in grilling Fremont was to force the dealer to say in his own words what happened next. Fremont could have lied. He could have said that he had no recollection of what happened to the pictures. But he didn’t. Instead, he recalled that the more he looked at the works seized from the studio of Rupert Jasen Smith, the more he came to feel that they resembled ‘other’ (presumably real, or at least authenticated) works already owned by the Foundation. He began to feel that “there was less and less there that was problematic – except for the signatures... and some sizes of some of the work, but they became, to me, worthy of review”. By “review”, he meant re-examination by the Authentication Board. “I suggested to the Foundation maybe that these should be reviewed again, by an independent body – not by me, but by an independent body, being the Authentication Board.”

This “independent body” was, of course, chaired by Foundation president Joel Wachs, staffed by three full-time employees of the Foundation, and advised by Fremont himself – who attended every one of its meetings in his capacity as a “consultant”. These 44 works were no different from hundreds of others made by Smith, except for a few important details: the size of the canvases on which some were printed was different from that of their authentic counterparts, and all but three of the pictures were fraudulently signed with Warhol’s name by someone clumsily imitating the artist’s signature. Whereas an argument could be made for authenticating a great many of Smith’s illicitly printed works, the fake signatures on these paintings meant that they were made with the intention to deceive.

Fremont continued his testimony. On his recommendation, the pictures were sent to the Board for re-examination. In June 2003, The Andy Warhol Foundation’s Neil Printz and Sally King-Nero looked at the paintings again. When Simon’s lawyer asked what happened next, Fremont replied that the pictures ‘went through the normal process. Some were authenticated, some weren’t.’ Kerr asked Fremont point blank whether he had ever sold work owned by the Foundation that its own Board had authenticated. His reply was unambiguous: “There’s only been one occasion, which would be the Fred Dorfman paintings.” To my mind, this would seem to indicate bigger and wider problems for all involved. Kerr’s next question sought to clarify the degree to which Fremont had been party to the deception. It required a yes or no answer. Were the works the Board authenticated at the meeting in 2003 authorised by Andy Warhol? Under oath, Fremont’s response was, “I don’t know, factually.”

Yet, back in 2003, Neil Printz had told Fremont that the estate “deemed” these paintings to be “inauthentic”, to have been “created under false pretenses” and to have signatures that were “not good”. Knowing this, Kerr pressed Fremont to say what it was that made the works authentic. Fremont answered that the Board ‘declared them to be genuine’. No other reason was given. Fremont, the person who confiscated the works as fakes, was the same person who advised the Board that authenticated them, and, of course, the same person who could and did sell them as authentic.

By the autumn following his deposition, Fremont no longer worked at the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Why did Fremont tell the truth? Because documents showing that these events took place had been handed over to Simon’s lawyers during the discovery period. If he had lied, and if the case was to go before Judge Swain, he could have been charged with perjury. So he said it had happened on only one occasion – the one for which Simon’s lawyers had documentary proof.

Fremont never acted alone. Before he could sell a painting, he needed the Board’s approval. Furthermore, in his deposition, Joel Wachs stated that he personally approved every painting Fremont sold that was owned by the Foundation.

The Foundation retained the sales, storage and insurance records relating to these paintings. In defiance of the court order, they were withheld during discovery. We therefore know that the sales took place, but do not have the dates or know to whom they were sold. If forgeries as relatively crude as these had been declared authentic, what about the thousands of Warhols with similarly dubious provenances without any obvious signs that they were created to deceive? It is hard to believe that, if some of the 44 Smith works were authenticated, many others just like them had not been treated in the same way.

Armed with the knowledge that someone at the Foundation had sent the 44 fakes to the Board, Kerr now stepped up his interrogations. The new information explained the unease I had picked up about the relationship between the Andy Warhol Foundation and the Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board.

Fremont declared that both he and Wachs sat in on meetings of the Authentication Board in a non-voting capacity. Why? Both men worked for the Foundation, not the Board. Was it possible that, when it came to the authentication and sale of Warhol’s work, Board and Foundation were essentially one and the same thing? If that was the case, then what happened when pictures owned by the Foundation came up before the Board? Someone had to be in overall charge – and it was not ( board members) Printz and King-Nero, or its secretary Claudia Defendi. They were infantry. They did what they were told. Who was lying? Foundation president Joel Wachs or its CFO KC Maurer? My guess is both.

The catalogue entry states flatly that the picture is “signed twice and dated ‘Andy Warhol 79–86’”. Of course, it is signed – but the signature is worthless..

But that was in the future. Kerr was unable to follow up his interrogation because the hearings were about Simon’s painting, not the 44 fakes. But the author of this book has no such constraint. Several years later I was able to read the minutes for the meeting of the Authentication Board held on 23 June 2003. This was the one during which Neil Printz emphatically rejected Fremont’s suggestion that the paintings were authentic, the one when the Board refused to authenticate the paintings on the grounds, among others, that ‘some signatures are bad’.

The minutes of that meeting take the form of swift jottings that are often left in fragmentary form, but clearly it is Printz speaking:

... this is a grey area, paintings coming out of Rupert’s studio that Warhol never saw. The signature is not so secondary in this case, the paintings all have the same problem. Why are these paintings different? Warhol did work that way, but the circumstances under which these were made was inherently dishonest. Paintings: there is no clear edition [ie a specific group of paintings of which Warhol had been aware] so that RJS [Rupert Jasen Smith] was making the paintings without [Warhol’s] knowledge, how many does RJS make – should they be out in the world as Warhol’s[?] – no, they should not be. Conclusion: these paintings should be given a B letter of opinion [denied] or a studio of Rupert Jasen Smith letter’ [meaning the work was made by Rupert Jasen Smith, not Andy Warhol].

Any competent, independent art historian would have said the same. That should have been the end of the matter. But then something unusual happens. The notes for the meeting conclude with a postscript: the issue of the authenticity of these paintings is to be “discussed again in the October 2003 meeting”. Why? The discussion was over. The issue should have been settled, the discussion ended. But it wasn’t.

At the next meeting, on 23 October 2003, the Board concluded that, after all, most of the 44 paintings were genuine works by Andy Warhol. Those that were not authenticated on the spot were once again “held over” to be discussed at future meetings. Thus, setting aside Printz’s objections, the Board oversaw their transformation from worthless fakes into original works by Andy Warhol. Fremont was now able to sell them as genuine, thereby enriching the Foundation with many millions of dollars, and taking a commission of as much as 10 per cent on each sale.

On what basis did those in attendance at the meeting on 23 October reverse their earlier conclusion? How did they justify their about-face? The answer is that we do not know, and that is the most corrosive evidence of all. Despite a federal court order to hand over “all relevant documents”, the minutes of the 23 October meeting are missing. By law, the foundation’s law firm Boies Schiller and Flexner was required to produce them on behalf of their client but, as it transpired, those crucial minutes would never be seen either by Simon’s lawyers or by a judge.

The same individual or individuals overturned the Board’s decision of the previous June. How that was done – by putting pressure on Printz, perhaps, or by overriding his objections – we do not know. Whether he acted alone or with others, only Joel Wachs had the authority to sign off on both the authentication and on the sale. Fremont merely conducted the transactions.

What about Printz? At the June meeting, he had insisted the paintings were fakes. If he acquiesced in the authentication of the same pictures in October, he might have been accused of being an accessory to a crime. Rather than put him in that position, perhaps he had been told to stay away. But that does not exonerate him, because he could have refused, or resigned, or both. We need to see those minutes to know what happened.

When I wrote about this in the New York Review of Books, for the issue dated 23 June 2013, I did not include the titles of the 44 works, nor did I say how many had been authenticated. But, a few months later, I was looking through documents related to the lawsuit when I found myself holding a piece of paper that told me everything I wanted to know. It was a list of the 44 paintings confiscated in 1991 from the Smith estate. It had been drawn up after the Board meeting in October 2003, giving the title of each painting and an ‘approval number’ indicating its status. “A” was a certificate of authentication enabling the Foundation to sell the picture – potentially for millions of dollars. The ‘B’ rating meant it was not by Warhol and was therefore worthless. “C” meant the Board had not yet made up its mind, so the work was in limbo. There was not a single ‘B’ on the list.

The Board had passed judgement on all 44 paintings. Of these, 35 received an “A” grade, meaning that they were authentic. The nine remaining paintings were given ‘C’ status, so that the Board could, whenever it chose, wave the magic wand that only it possessed to transform the former fakes into authentic works by Andy Warhol. The next question was: did the Foundation sell these works? I looked again at Fremont’s pre-trial deposition. Asked whether he had ever sold work owned by the foundation and authenticated by its own authentication board, he replied that he had, once: “the Fred Dorfman paintings”.

I published this information in the November 2013 issue of the Art Newspaper, which printed not only the list of the 44 pictures, with the grade (”A” or “C”) next to each but also the inventory number of every picture on the list. I assumed that someone on the Board or at the Foundation must have been tasked with washing off the inventory numbers, but I still hoped that owners who had acquired any painting directly from the Foundation, or from dealers who had worked closely with the Foundation after 2003, would be able to determine whether their work was among the fakes. If any had not been sold, then in theory, publication of the inventory numbers would ensure that, if the Foundation offered them for sale, they would be obliged to provide a full provenance. Again, the inventory number would have been washed off, but perhaps some trace or smear might have been left in the process.

The person at the Art Newspaper who edited my article therefore inserted a single sentence at the end: “We [at the Art Newspaper] also invite any concerned parties to contact us.” To date, none of the 44 paintings has been securely identified. This could be for several reasons. After the appearance of the piece in the Art Newspaper, the Foundation could have contacted dealers who bought regularly from Fremont, alerting them to the problem. It was then up to the dealers to speak directly to any clients who had bought one of the 44 paintings, offering to replace the painting or reimburse them if they were dissatisfied. Any such deal would have been contingent on signing a non-disclosure agreement. There is another possibility: if Fremont informed the dealers to whom he sold the newly authenticated pictures of their complex history, those transactions would not necessarily have been questionable. But there is a further complication. Even if Fremont frankly told a buyer that a picture’s status had recently changed from fake to real, how do we know that the dealers told their clients all the facts? And, if a dealer was aware of the picture’s history and yet still sold it on without informing his client, which person in the chain is legally responsible?

Here’s an example of how difficult it can be to assign responsibility in these cases. Among the emails handed over by the Foundation and included in Simon’s letter to Judge Swain is an exchange between a representative of an auction house in London and Sally King-Nero. The auction house was about to hold an evening sale, which included a few works by Warhol. On 4 May 2007, the researcher who was writing the sales catalogue followed the correct procedure and asked King-Nero about numbers inscribed on the reverse of a Four Marilyns painting which is dated 1979–86. The researcher was confused because it was stamped with the Authentication Board numbers “B291.03” and “A291.1”. She knew that an “A” prefix meant the painting was genuine, and that the “B” meant it was not by Warhol. In her reply of 14 May, King-Nero explained that the “A” referred to the painting, the “B” to the signature. OK. So the Board considered the picture authentic, but not the signature. So far, so straightforward.

Now watch what happens. The auction house then had a policy of giving owners of fabulously expensive pictures a guarantee that they will receive an agreed sum whether their picture met its reserve price or not. That meant the auction house had a strong financial incentive to present the work in the best possible light. If we turn to the printed sales catalogue, the “A” prefix verifying the picture’s authenticity is recorded, but not the ‘B’ signifying that the signature is not Warhol’s. The catalogue entry states flatly that the picture is “signed twice and dated ‘Andy Warhol 79–86’”. Of course, it is signed – but the signature is worthless.

Warhol After Warhol by Richard Dorment is published by Picador

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks