Born out of ruins: the fearless art of Anselm Kiefer

William Cook meets the artist who shows that, though life is cruel and mankind destructive, amid the rubble and scorched landscapes of our lives there is always hope

Entering Anselm Kiefer’s latest exhibition, at London’s trendy White Cube gallery, the first thing you encounter is a huge heap of sand. Cast upon it are several shopping trolleys and a dilapidated wheelchair. On the wall alongside it hangs one of Kiefer’s large and complex paintings – a bedraggled crowd advancing across a barren plain towards a great burst of light.

This painting encapsulates the core theme of Kiefer’s work, a theme he’s explored throughout his illustrious (and lucrative) career: life is cruel and mankind is destructive, but amid the ruined landscapes of our lives there is always hope.

In the next room, you emerge from twilight into daylight. Around the walls are a series of pastoral paintings: an iridescent river running through a verdant landscape. They’re supremely peaceful, yet darkness is never far away. Books are strewn across the floor, each one the size of a suitcase. When you look closer, you realise they’re made entirely out of metal.

It’s a neat irony that these gigantic books are impossibly heavy, because the inspiration for this one-man show is that unreadable masterpiece, Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. Kiefer loved Joyce’s Ulysses, but for a long time he found Finnegans Wake unfathomable, until he started listening to it rather than reading it, and learnt to let it wash over him, like music.

Kiefer arrives quietly, without ceremony, a spectator at his own private view. Like most truly creative men, he’s calm and unassuming. Bald, bearded and bespectacled, with the lean physique of a lifelong athlete, he wears his 78 years lightly. He’s dressed in a white T-shirt, fawn suit and hooded overcoat. He looks like Alec Guinness playing Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars.

He sees a lot of parallels with Joyce, not least the author’s insatiable appetite for re-editing. “I never say a painting is finished,” he says. “I always get it back, after 20 years sometimes, and I redo it.” Like Joyce’s writing, Kiefer’s art is multi-layered – cryptic and opaque. You need to go with the flow, rather than trying to work out what it means. Likewise, you can still enjoy this show without reading Joyce’s magical, impenetrable novel. For Kiefer, Finnegans Wake was merely a starting point, simply the latest spur for his restless, boundless imagination. “He makes a new language,” says Kiefer. “He destroys it and he reconstructs it.” He’s talking about Joyce, but he might as well be talking about himself.

Kiefer was born in 1945 in southwest Germany, two months before the end of the Second World War. On the night that he was born, his home was hit by Allied bombers, but because his father had brought his pregnant mother to hospital, no one was harmed. His birth saved both their lives.

Germany was utterly defeated, but there was no respite from the bombing. His parents stuffed his ears with wax to muffle the noise. His mother couldn’t produce any milk (malnourishment was rife) and so he nearly died. Mercifully, when he was two months old, Hitler killed himself and Germany surrendered. Kiefer emerged into a disgraced and devastated Fatherland, his hometown reduced to a moonscape of charred ruins. Germans called it Stunde Null – zero hour. Everything had been swept away.

For Kiefer, these flattened cityscapes were places of excitement and adventure. Bombsites were his playgrounds – they remained a central inspiration throughout his life. The centrepiece of this arresting new show, at White Cube, is a monumental heap of rubble. “A ruin is never the end,” he states, emphatically. “A ruin is the beginning.”

Kiefer’s upbringing was austere, but with no television and few toys he made his own entertainment. “All that I do has a connection with my childhood,” he says. He wasn’t close to his parents. He felt like a cuckoo in the nest. School stifled his creativity. He reacted by retreating into his imagination. As he told the writer and theologian Klaus Dermutz, “I dreamt of vast spaces and transported myself to another world.” It’s a good description of his art.

Kiefer initially studied law, but he ended up at art school and then gravitated to Dusseldorf, the new artistic centre of West Germany. In Dusseldorf he met the iconoclastic German artist Joseph Beuys, who was teaching at Dusseldorf Kunstakademie – then, as now, one of Germany’s leading art schools. Beuys became his mentor (Kiefer later called him “the first one to understand me”). A veteran of the Second World War, Beuys could see that for German artists, the moral catastrophe of the Holocaust necessitated an entirely new approach to art, and in Kiefer he recognised a kindred spirit.

The artwork that made Kiefer’s name was controversial, to say the least. Occupations was a series of vainglorious photos of Kiefer in scenic locations in France, Switzerland and Italy, giving the notorious Sieg Heil salute, aka the Hitlergruß. Carried out today, this would seem like tasteless attention-seeking of the worst sort, but back in 1969 it broke a powerful taboo.

After the privations of the post-war years, West Germany had enjoyed 20 years of remarkable economic growth (what Germans call the Wirtschaftswunder – the “economic miracle”), and most West Germans were keen to work hard, enjoy the good life and forget about the Third Reich. Just as bourgeois West Germans mimicked the American bourgeoisie, West German artists mimicked American artists, aping transatlantic genres like Pop Art and Abstract Expressionism, rather than finding their own style.

For Kiefer, this was a cop-out. Artists should address the realities of their own societies, and the reality of West German society was that the Third Reich, which had embarked on a genocidal war of conquest only a generation earlier, was now confined to history books, and largely absent from public discourse. Kiefer’s father had been in the Wehrmacht. For Kiefer, forgetting was not an option. The Holocaust was never mentioned, and he thought that was crazy. He set out to challenge that through art.

In Occupations, Kiefer cut a ridiculous figure, saluting alone in empty parade grounds, like Cnut trying to turn back the tide. For anyone with any sense, the satirical content of this work was clear. It lampooned the Nazis, but it was also a reminder of what had gone before. Occupations was Kiefer’s crie de coeur, supported by detailed research into Nazi Germany. Today, the German Bundesrepublik is widely admired for its honest, painful appraisal of German crimes against humanity. Artists like Kiefer played a significant part in promoting this sea change, forcing Germans to confront the past.

If Kiefer had confined himself to this sort of provocative performance, his flame would have burned brightly but briefly, like so many conceptual artists of the 1970s. Instead, he turned to painting, and his career flourished. Working on a grand scale, he tackled aspects of German history that the Nazis had appropriated and corrupted, like the operas of Richard Wagner. “Wagner’s music is fantastic,” he tells me. “He was an antisemite, yes – but the music is really fantastic.” Most German artists had steered clear of these subjects, reluctant to court controversy, but Kiefer was fearless. These subjects were part of Germany’s history. To ignore them made for bad morals and bad art.

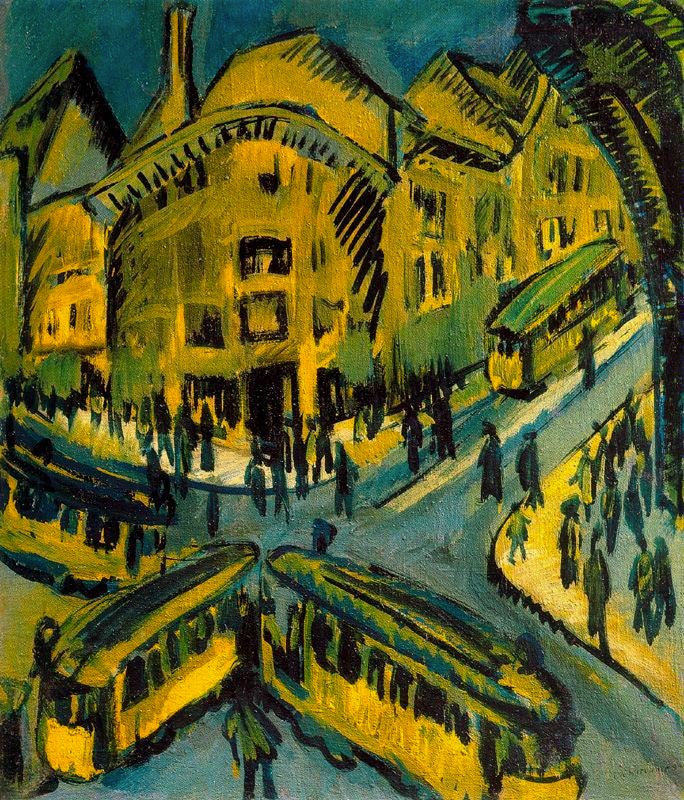

It wasn’t just Kiefer’s subject matter that set him apart – it was the style and substance of his painting. Back then, hi-tech novelties like video art were commonly considered to be the next big thing, and figurative painting was widely regarded as old-fashioned and outmoded. In this sense, Kiefer was a refreshingly traditional, even conservative artist, harking back to the German Expressionist painters of the early 20th century, like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and German Romantic painters of the early 19th century, like his hero Caspar David Friedrich.

However, there was nothing conservative about the way Kiefer applied paint to canvas. His approach was more sculptural than painterly, applying layer after layer, incorporating all sorts of elements: mud, tar, ash and straw – even gold leaf and molten lead. He attacked his pictures with an axe and a flamethrower. He poured water on them. He walked all over them. He left them out in the sun and rain, at the mercy of the weather. These weren’t landscape paintings so much as chunks of landscape, ripped from the earth and hung upon a wall. In 1987, the late great art critic Robert Hughes called Kiefer “the best painter of his generation on either side of the Atlantic”. His interests weren’t confined to German history. His preoccupations ranged from quantum physics to the Old Testament.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, made Kiefer’s work even more relevant. The reunited Germany was founded upon a frank recognition of its awful past. Kiefer’s historic paintings, which addressed topics many German artists had shied away from, took pride of place in new galleries like the Hamburger Bahnhof, Germany’s equivalent of Tate Modern, housed in an old railway station beside the former “death strip” of the Berlin Wall.

Although he began his career by addressing the dark chapters of Germany history, his current work feels universal. “I don’t do daily politics,” he says, “but I read the newspaper, I watch TV, I’m very well informed.” Having grown up with the clear dichotomy of the Cold War – capitalists in Western Europe, Communists in the East – he finds today’s geopolitics far more complex. “It gets more and more complicated.” Yet his timeless work speaks to every epoque, especially in times of war.

Kiefer has been honoured with retrospectives at the world’s most prestigious galleries: London’s Royal Academy; New York’s Museum of Modern Art; the Pompidou in Paris; the Guggenheim in Bilbao. He’s the only living artist on permanent display in the Louvre. However, the greatest Kiefer show of all is at Barjac, a derelict silk factory in the South of France where he’s lived and worked, off and on, for the last 30 years.

Barjac can be seen as the apotheosis of his art, the recreation of his gargantuan paintings in three dimensions – what Germans call a Gesamtkunstwerk, a multifaceted, entirely integrated work of art. In this secluded corner of the French countryside, he built a dystopian, dreamlike labyrinth of brutalist towers and tunnels to house his artworks and what he calls his arsenal.

This arsenal is Kiefer’s enormous repository of junk and bric-a-brac – stuff most of us would regard as rubbish. This is his source material – not just the inspiration for his art, but its raw components. In a departure from his previous exhibitions, a substantial part of this arsenal features in his White Cube show (though it’s only a fraction of the total – he never throws anything away).

As you walk along the corridor, from room to room, you pass endless vitrines and cabinets filled with all sorts of curios: a rib cage in a cardboard box; a rusty bicycle; a procession of stiff, paint-splattered overalls hanging from a clothes rail... This isn’t an offshoot of the exhibition – the paintings and the sculptures are the offshoots. It’s like stepping inside his head.

After the private view, I grab a few minutes alone with him, and I ask about those river paintings – so serene and life-enhancing, so unlike his darker work. I thought they were pictures of the Liffey, the river in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, but it turns out I was wrong. “I made them from photos of Rhine landscapes,” he tells me. “This was the landscape of my childhood.” This was where he used to swim.

Kiefer is a painter and a sculptor, but the distinction between these two genres feels arbitrary. His paintings are almost three-dimensional. All his art comes from the same source. The seismic shock of his early years gave his work terrible beauty and terrific confidence. After he’d uncovered the horrors of the war years, he had nothing left to fear. Yes, his work is often harrowing, but like all great art it’s invariably exhilarating, even when he’s confronting the darkest deeds of humankind.

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno said that to write poetry after Auschwitz would be barbaric. The same could be said of making art. This was an immense problem for German artists of Kiefer’s generation. How could they ignore the Holocaust? Yet how could they face up to it?

Kiefer found a way to do it – partly because he was blameless, a baby when the war ended, but above all because his art is enigmatic, not didactic. It’s never shrill or strident. He never tells us what to think. As we say goodbye, I remember something he said last time I met him. “I always allow people to see what they want to see. Anyone who sees the painting has another painting in his head.”

Anselm Kiefer – Finnegans Wake is at White Cube (whitecube.com), London SE1, until 20 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks