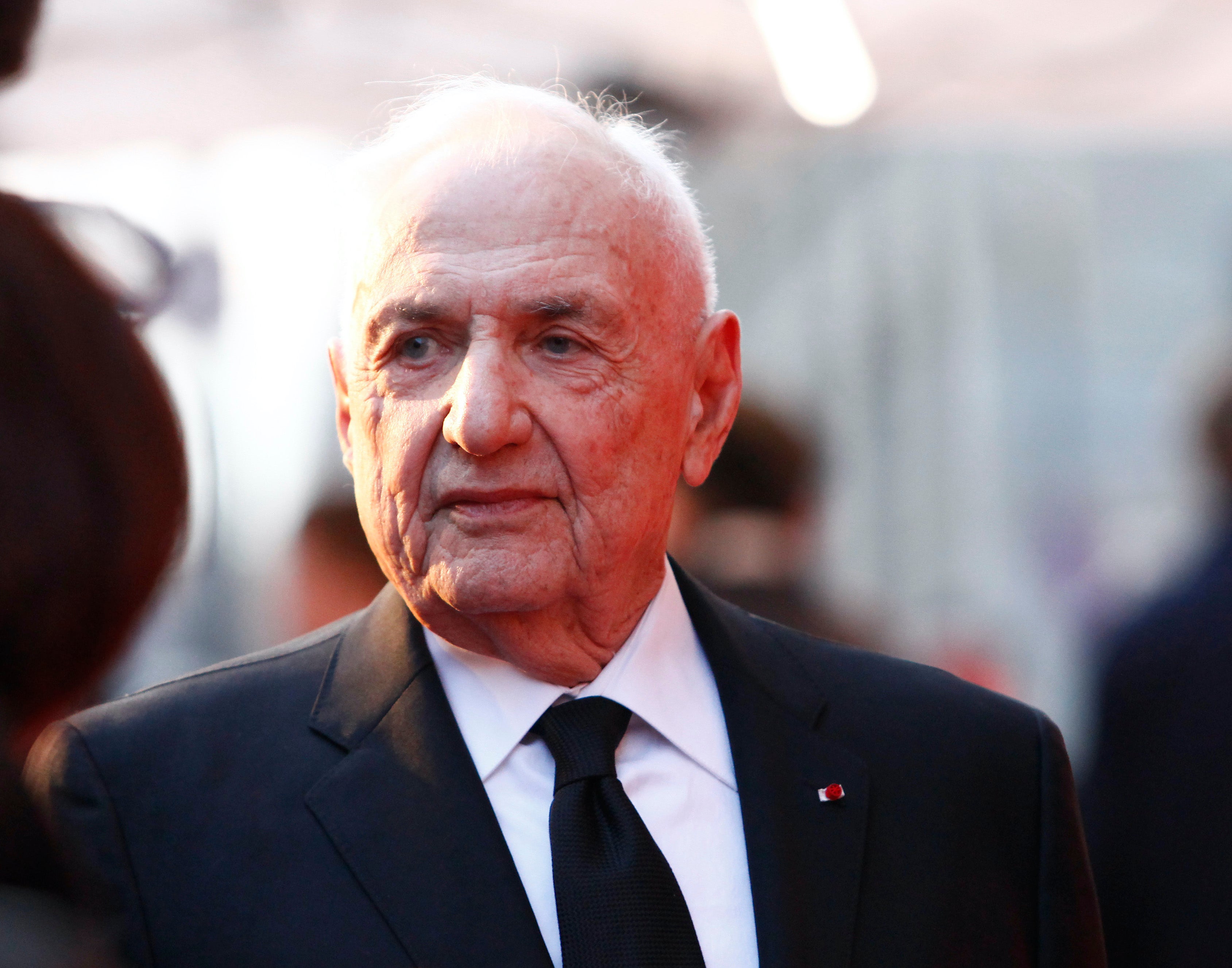

Frank Gehry: ‘I can look at projects and see all the things I should have done differently’

The award-winning architect speaks to Robin Pogrebin about reflecting on his past work, new projects, and why he has no plans to scale back

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s mid-afternoon on a Monday and Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry – despite having just turned 92 in a pandemic, completed the top floor of his building in the Grand Avenue development, and prepared for a show of new sculpture at the Gagosian Gallery – has little interest in sitting back to reflect on this potentially meaningful moment in his life and career.

Instead, he’s on the move – giving his first studio tour since the Covid-19 outbreak, far more eager to discuss the myriad designs he has underway, most of which have been proceeding. (Only a high-rise in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards stalled, and his office laid off eight of 170 employees as a result.)

Projects include LA's version of New York’s High Line, along the Los Angeles River; new office buildings for Warner Bros. in Burbank; and the scenic design he’s doing for a jazz opera, “Iphigenia,” by Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding, which is heading to the Kennedy Center in Washington in December. Nearly 3,000 miles away, the Philadelphia Museum of Art is set to unveil its Gehry-designed renovation and interior expansion in May (an event the architect plans to attend).

Asked whether, given his age and accomplishments, he has considered taking a break or scaling back, Gehry dismisses the idea.

“What would I do?” he says. “I enjoy this stuff.”

Buzzing through his sprawling work space, the architect says he has reached a point in his career where he has the luxury of focusing on what matters to him most: projects that promote social justice.

“I’m just free,” he says, “now that I don’t have to worry about fees.”

Gehry’s increasing emphasis on giving back seems to have intensified his commitment to this city. He is, for example, designing housing on Wilshire Boulevard for homeless veterans. And about six years ago, he and activist Malissa Shriver founded Turnaround Arts: California, a nonprofit that brings arts education to the state’s neediest schools.

“These are labours of love,” Gehry says.

He has volunteered his time in designing a new home for the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s youth-focused educational arm, Youth Orchestra Los Angeles (YOLA), in the Inglewood Civic Center south of the city, to be completed in June.

Gehry says he was inspired by Venezuela’s publicly financed musical education program, “El Sistema,” which gives underserved children the chance to play in orchestras. A product of that program, Gustavo Dudamel, the music and artistic director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic who fills the same roles for YOLA, called the Gehry creation “a metaphor that says, ‘Beauty matters’”.

In transforming a 1960s bank building into a concert hall for the youth orchestra, Gehry says he pushed the organisation to raise a little extra money to achieve a 45-foot theatre, the same size as his Walt Disney Concert Hall.

“It pops up,” he says, “like a lighthouse for the community.”

Gehry – who designed a centre for the New World Symphony in Miami as well as the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain, and the Guggenheim’s branch planned for Abu Dhabi – remains animated by cultural projects with an educational component (he recently joined the board of the Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz, a nonprofit organisation that trains promising young musicians).

He is perhaps most energised about the River Project – an effort funded by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works to revitalise the 51-mile channel that runs from Canoga Park to Long Beach and was paved over in 1938 to prevent flooding.

River LA, a nonprofit group — with the support of Mayor Eric Garcetti — recruited Gehry to develop a master plan for the site. Out of that came the idea for an urban platform park over the concrete with grassy spaces and a $150 million cultural centre.

Called the SELA Cultural Center (named after its Southeast Los Angeles location), it will be financed with public and private funds and serve as a space for local artists as well as professionals.

But some have criticised Gehry’s involvement in the project – a public comment period on the plan ended recently – as big-footing community leaders, lacking experience with outdoor space and inviting gentrification.

“The potential for a tragic backfire is huge,” warned a recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Times. “We could pour millions of public dollars into a plan that looks impressive but drives out its target audience — communities that have found it hard just to survive in recent decades.”

Gehry has tried to address such concerns and emphasised in an interview that his focus was on creating affordable housing and open space.

“We’re working on social housing opportunities,” Gehry says, “to promote homeownership among the existing population.”

Nevertheless, activists remain unhappy about Gehry’s approach to the project, preferring to return the tributary to its original state.

“As famed as Gehry is, and as much as that fame has brought attention to the river, there is no better architect than Mother Nature,” says Marissa Christiansen, executive director of Friends of the LA River, an advocacy group.

Gehry’s current proposal “shows a lack of innovation and comprehensive understanding of the watershed that feeds the river,” she added. “It hasn’t been fully studied yet to see if there are other possibilities.”

Gehry, as the face of his firm, remains the target of such criticism, but Gehry Partners is made up of long-serving members who work closely with him, including his wife, Berta, Meaghan Lloyd, David Nam, Craig Webb, Tensho Takemori, Laurence Tighe, John Bowers and Jennifer Ehrman.

The operation has become something of a family affair. In addition to Berta Gehry, the head of finance, Gehry’s son Sam is also an architect (he designed his father’s new Santa Monica home), and his other son, Alejandro, is an artist who contributes work to his father’s projects. (Gehry’s daughter, Brina, teaches yoga in New York.)

“We’re a mom-and-pop shop,” Gehry says.

While he can be a lightning rod on the River Project, he is also engaged in more lighthearted pursuits, such as his reinterpretation of the Hennessy X.O bottle for the cognac’s 150th anniversary last year: a crinkled sleeve of 24-carat gold-dipped bronze, encased in sculptural glass.

Inspired by his 5-year-old granddaughter, who calls him “Nano,” Gehry created an oversized “Alice in Wonderland” tea party, complete with a Mad Hatter. That piece, along with colossal vertical fish lamps of polyvinyl and copper suspended from the ceiling, will be featured in Gehry’s sculpture show, opening June 24 at Gagosian’s Beverly Hills space.

“Late in his life, he’s really free to be creative without compromise or collaboration,” says Deborah McLeod, senior director of the gallery. “How much fun this is for Frank Gehry to make whatever he wants.”

While the architect appears slightly more stooped and his hair more wispy, he continues to exude a childlike excitement about design details. Like how he played with blocks of metal for Swiss art patron Maja Hoffmann’s $175 million arts complex, Luma Arles, scheduled to open in late June. How he’s experimenting with a softer metal to achieve the effect of a watercolour painting with his design for a museum of medicine at China Medical University in Taichung, Taiwan. “By folding the metal,” Gehry said, “you will get a beautiful surface.”

And how he used white glass for his Warner Bros project along the Ventura Freeway, as he did for Barry Diller’s IAC world headquarters on the West Side Highway in New York City. “I thought of them like icebergs,” Gehry says of his buildings, “floating along the freeway.”

Dressed in a blue T-shirt and brown corduroys, his reading glasses perched atop his head, the architect talks about how much he has enjoyed his give-and-take with Jeffrey Worthe, the developer of the Warner Bros. project, for whom Gehry is also designing a hotel complex on Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica. “He cares about architecture,” Gehry says.

Worthe, for his part, said he has been surprised by Gehry’s openness to input and cost savings. “He never thinks it’s perfect,” Worthe says, “never thinks he’s got all the answers.”

That is not to say that Gehry doesn’t retain a healthy ego. In talking about the popular contemporary art museum he designed for the Louis Vuitton Foundation in 2014, the architect said, “I think we nailed it pretty good.”

And he clearly takes pride in designing private homes for prominent clients, such as the elegant family compound in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, for Hassan Mansur of the Surman automotive group. Or the Colorado “Meeting House” he designed with a contoured stainless steel roof for Michael and Jane Eisner in 2018.

Perhaps most notably, Guggenheim Bilbao made the idea of destination architecture de rigueur, though Gehry said he is focused on the challenges ahead, not what he has already accomplished.

“I don’t know if I take credit for anything,” Gehry says. “I’m not that interested in that.”

“I’m proud of what I’ve done,” he continues, “but I can look at projects and see all the things I should have done differently.”

One project retains a special pride of place: the pair of towers that are part of the King Street development in his native Toronto – the architect’s tallest project to date.

“New York has Rockefeller Center; it’s a coherent architectural piece and it lasts, it holds its own,” Gehry says, adding that he hoped his King Street effort “holds together like that.”

“My grandmother’s street is just up there,” Gehry said, pointing to a rendering on the wall. “My grandfather’s hardware store was here. So I hung out on this street.

“The city gave us extra height,” he adds, “because it was me coming home.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments