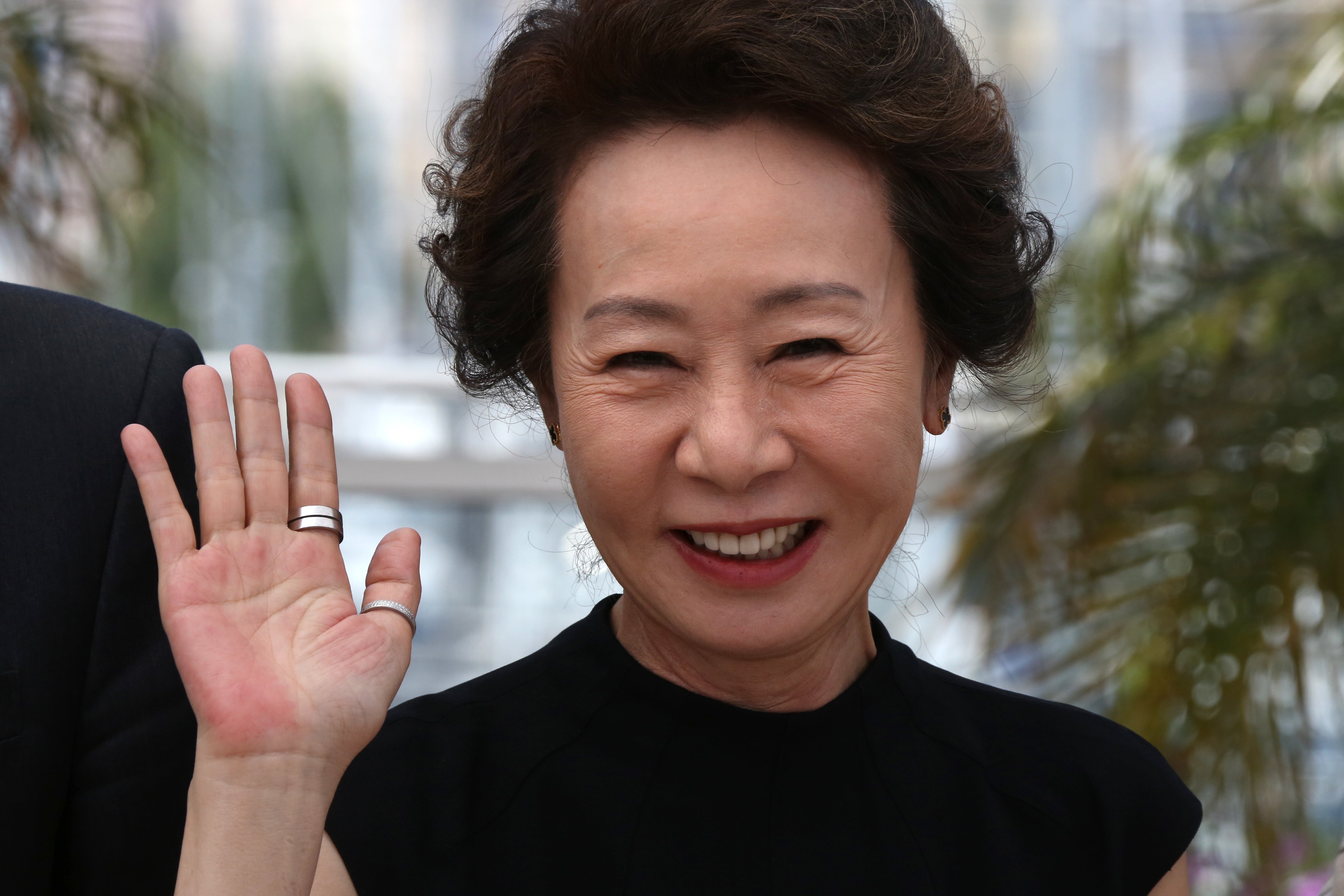

‘Minari brought me a lot of gifts’: Yuh-Jung Youn never even dreamt about being nominated for an Oscar

Yuh-Jung Youn never thought a 73-year-old Asian woman would end up nominated for such prestigious awards. She spoke to Carlos Aguilar about her life and career and how she came to star in Minari

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For her 60th birthday, veteran Korean star Yuh-Jung Youn made herself a promise. She would collaborate only with those she trusted. Even if their ventures fell short, as long as she personally appreciated the people making them, the result wouldn’t much concern her.

That late-life philosophy, born of decades of limited choices and professional trauma, brought her to Minari, director Lee Isaac Chung’s semi-autobiographical story about a Korean family putting down roots in Arkansas. Youn’s bittersweet performance as the grandmother, Soonja, in the tender-hearted immigrant drama has earned her an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actress, the first for a Korean actress.

“Me, a 73-year-old Asian woman could have never even dreamed about being nominated for an Oscar,” Youn said via video call from her home in Seoul. “Minari brought me a lot of gifts.”

Read More:

As she recounted this triumph and the many pitfalls that preceded it, her pensive expression often broke into an affable smile, cheerful laughter even. Dressed in a demure black top and long necklace, there was an effortless grace to her serene presence. She came off unhurried and welcoming but determined to make her ideas understood. Occasionally she asked a friend off-camera for help with certain English words to hit each point more precisely.

She expressed surprise at the fact that co-star Steven Yeun was the first Asian-American performer to receive a nomination for best actor: “All I can say is: It’s about time! The success of Parasite has definitely helped” get more recognition for Korean performers, she said.

Most people fell in love with the movies or fell in love with theatre. But in my case, it was just an accident

That movie, directed by Bong Joon Ho, was the first non-English language production to win best picture, and it has also affected Youn’s Oscar run in other ways.

She had returned from shooting a new project in Vancouver, British Columbia, an Apple TV drama titled Pachinko, just in time to hear the announcement of her nomination. First, she felt numb. Then the Korean news media began effusively reporting on her chances. “It’s very stressful. They think I’m a soccer player or an Olympian,” she said, adding, “That pressure is really hard on me. They have hope I can win. I keep telling him [Bong, the director of Parasite], ‘It’s all because of you!’”

Bong, a fan of director Kim Ki-young’s Woman of Fire, the 1971 film in which Youn made her feature debut, envied her awards-season experience during the pandemic. “He told me, ‘You’re lucky you can just sit down and do Zoom calls. In America they have an awards race and you have to go here and there and everywhere.’ I thought running races were only for horses,” she said.

She’s making a strong push to the finish. Youn is nominated at Sunday’s SAG Awards for her performance and as part of the Minari ensemble. She’s also up for an Independent Spirit Award later this month. And she’s already won accolades from more than 20 groups of critics.

They’re the latest turn in a career that spans more than 50 years in Korean television and film — including a recent cooking reality show titled Youn’s Kitchen and a new nonfiction series set in a guesthouse, Youn’s Stay — but the self-taught thespian never envisioned a life in the performing arts. Her international breakthrough seems to her, like everything else along the way, fortuitous.

“It’s embarrassing,” she said. “Most people fell in love with the movies or fell in love with theatre. But in my case, it was just an accident.”

When she was a teenager in the early 1960s, an emcee for a children’s game show saw her touring a TV station and invited her to pass out gifts to the audience: “I got the check after that, and it was good money.” Similar jobs ensued until a director suggested she audition for a drama. Although she was hesitant, necessity propelled her: she had failed her college entrance exam, causing her mother profound shame, she said. (After publication of this article online, her representatives clarified that she passed, but with a low score that meant she couldn’t get into a top-tier college.)

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t know what acting was,” she said. “I tried to memorise the line and do whatever they asked me to do. At the time, I didn’t know if I was enjoying it or if I disliked it.”

But as she was on the rise in the mid-1970s, Youn married and moved to Florida, where her husband attended university. She spent nearly a decade as a housewife raising her two American-born children, but then she divorced and returned to Korea as a single mother. Her fame had vanished, and ingrained sexism in Korean society made resuming her career a cruel pursuit. “The audience would call and say, ‘She is a divorcee. She shouldn’t be on television,’” she recalled, adding, “Now they like me very much. That’s very strange, but that’s human.”

To put her two sons through college, she accepted parts almost indiscriminately. But turning 60 — and no longer obligated to financially support her family — meant she could invest only in people she believed in, such as auteur Hong Sang-soo, who occasionally frustrates her for the many takes he requests, and Im Sang-soo, who cast her in roles practically unheard of for a Korean actress of her age. In The Taste of Money (2013), for example, Youn embodies a powerful woman who sexually harasses her younger male secretary.

I didn’t go to acting school and I didn’t study film, so I had an inferiority complex. I practiced so hard when I got a script

Youn’s close friend In-Ah Lee, a producer, introduced her to Chung at a film festival in Busan. Chung, like Bong, revered her in Woman of Fire, and his knowledge or her early work impressed her. She wanted to know more about him. “Everybody teases me about this now,” she said. “I fell in love with Isaac because he is a very quiet man. I wish he was my son too.”

In every film, Chung said via email, “she does something that is surprising or unexpected. I felt her own life and approach to life were very close to the part I had written.” He added that the actress is known in South Korea for her big heart and no-nonsense manner, and he knew she would bring those qualities to the Minari role “in a way that invites audiences in”.

Writing for The Nation, critic Kristen Yoonsoo Kim said Youn “steals the spotlight; even as she leans toward caricature, her Soonja brings much-needed humour and vitality to a drama that could otherwise sink easily into the dour.”

When Youn read the script, the perils of the Korean American experience and how it doesn’t fit neatly into a single identity resonated with her. “Maybe I did this movie for my two sons too, because I knew their feelings,” she said.

Chung won her over when she asked if he wanted her to imitate his grandmother and he replied that that wasn’t his objective. She valued the freedom to create a character beyond what was on the page. Yet it was Chung’s empathetic approach that she came to cherish.

She recalled the chaotic first day of filming Minari in the heat of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Chung could see she was suffering, Youn recalled. “I could feel his respect and worry for me.”

By contrast, she admitted, she thought the many scenes she shared with Alan S Kim, an inexperienced young actor who plays her grandson, would test her patience. “I thought, ‘It’s going to be miserable. What am I going to do with this one?’” But when she realised the boy had memorised his lines, her worry disappeared. She shared his work ethic.

Read More:

Intense preparation had always served as Youn’s shield against self-consciousness about her background. “I didn’t go to acting school and I didn’t study film, so I had an inferiority complex. I practiced so hard when I got a script,” she said.

But she is skeptical about further prospects in Hollywood. Youn, who often apologised during the interview for how blunt she thinks she sounds in a tongue not her own, fears that her lack of English proficiency may impede her. But given time to learn her dialogue, she is willing to try.

“Come to think of it, it was all worth it,” Youn said. “At the time, I was suffering with only small roles and most people hated me. I thought about just quitting or going back to the States.” But she’s a survivor, she said. “I’m still alive and finally enjoying acting.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments