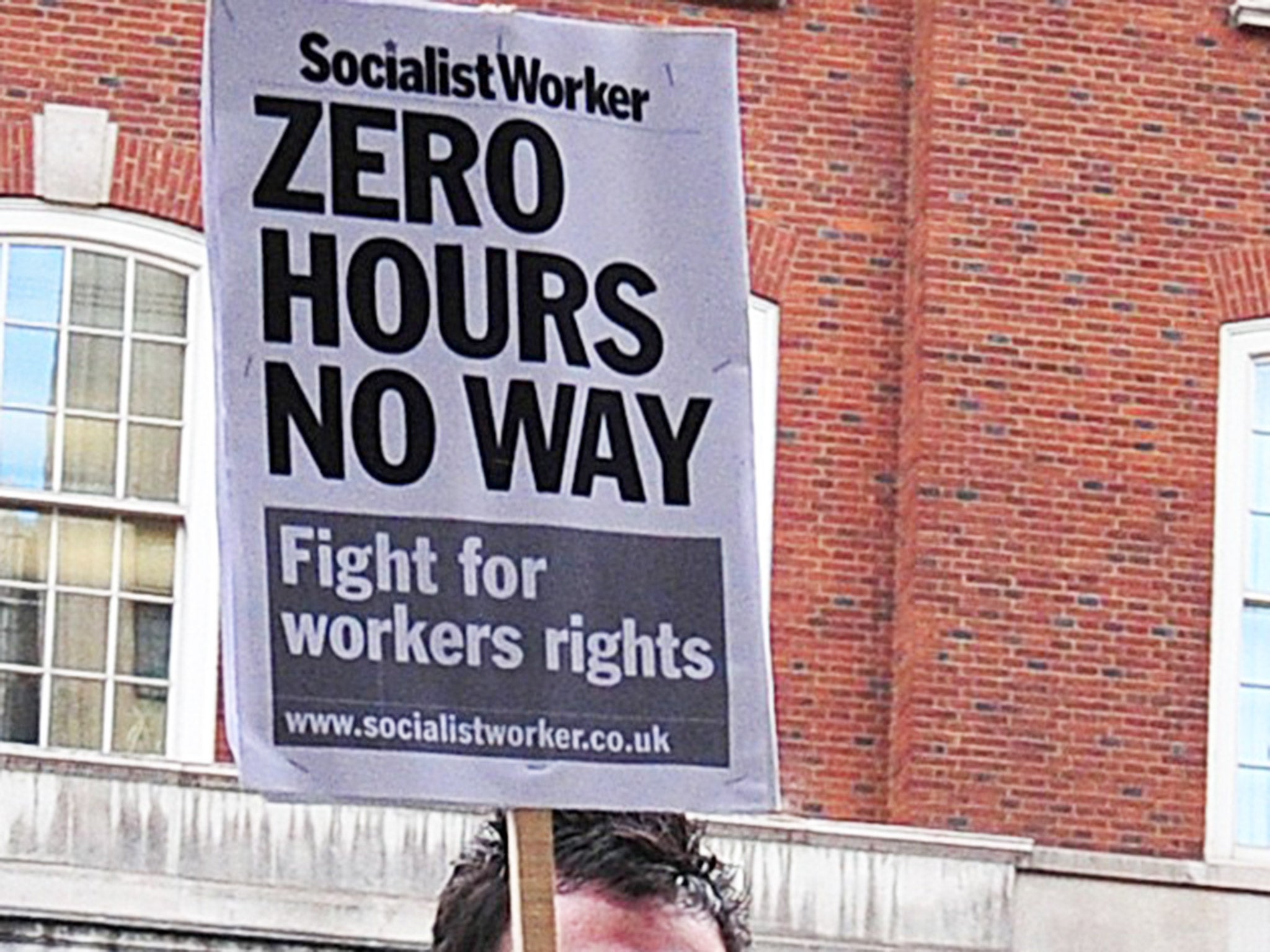

Zero-hours contracts have their place, yet they are abused by companies seeking to dodge their responsibilities

It should be possible to find balance between protecting our record for job creation with rights and needs of people

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few phenomena are as simultaneously popular and unpopular, it would seem, as zero-hours contracts. Popular, that is, at least in the sense that they have become such a familiar part of the working scene, increasing by 104,000 to 801,000 in a year. One worker in every 40 is covered, a remarkable figure given that they were more or less unknown a decade ago. That does not mean, of course, that they are popular in the sense of being liked – or, indeed, perceived as fair. Many rightly feel a sense of unease about the balance of power in these contractual relationships. Although it is true that they are, strictly speaking, freely entered into they obviously favour the employer much more than the worker, especially when compared with conventional contracts of employment that have a specified salary, working hours, holiday entitlement, pension contribution and other benefits.

The most pernicious of all, the exclusive zero-hours contract, has now been outlawed, under legislation pioneered by Vince Cable in the Coalition Government, but only now coming into effect. What we are left with is what are sometimes termed “ultra-flexible” contracts: non-exclusive zero-hours contracts that, in truth, do suit some employees.

The usual example is that of a university student, but there may be many others who are relaxed about changing plans at the last minute and whose lifestyle fits in well with such an arrangement. It may also sometimes be the case – though the reputation of these practices suggest otherwise – that hourly rates may be better than they might be in a conventional contract for the same job. Even so, the difficulty arises when zero-hours contracts solidify into a less secure, less well paid, less fair version of a permanent employment contract. Some flexible contracts are used by companies simply to cut wages and to avoid the benefits enjoyed by regular employees and agency staff. It cannot be acceptable for employers to have people in permanent posts masquerading as zero-hours “flexible” workers.

There are also equality implications: younger women in particular seem to be trapped in such contracts, and young people generally have to accept an ugly parody of the kind of well-ordered employment arrangements their parents and grandparents enjoyed.

Britain’s flexible labour market has, on balance, served the nation well so far. Unlike many continental European economies, Britain weathered the Great Recession with a relatively modest rise in unemployment, as companies, their staff and, in some cases, their unions co-operated to put jobs before pay rises – in marked contrast to past downturns when unemployment rose by millions as the economy slowed.

Although the recovery has been weak at times, job creation in the UK has generally been faster and more substantive than in many competitor countries. Many jobs are indeed of a low-skill, low-pay, temporary or part-time nature, including those covered by zero-hours contracts, but have at least been generated.

It should be possible to find a balance between protecting our enviable record for job creation with the rights and needs of people.

The latest figures suggest that we may still be a little way off that; but we would not expect a Government infused with free-market instincts to do much about it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments