I worked for Zac Goldsmith’s failed campaign – and this is what it looked like from the inside

I expressed my concern about racial profiling. Instead of being frustrated by the negative press coverage, senior campaigners told me the controversy was a good thing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A confession: less than a year ago, I was an idealist. I thought politicians got too hard a time, that they were fundamentally good, honest people. I didn’t understand the widespread dissatisfaction with politics. I thought the public was negative and cynical.

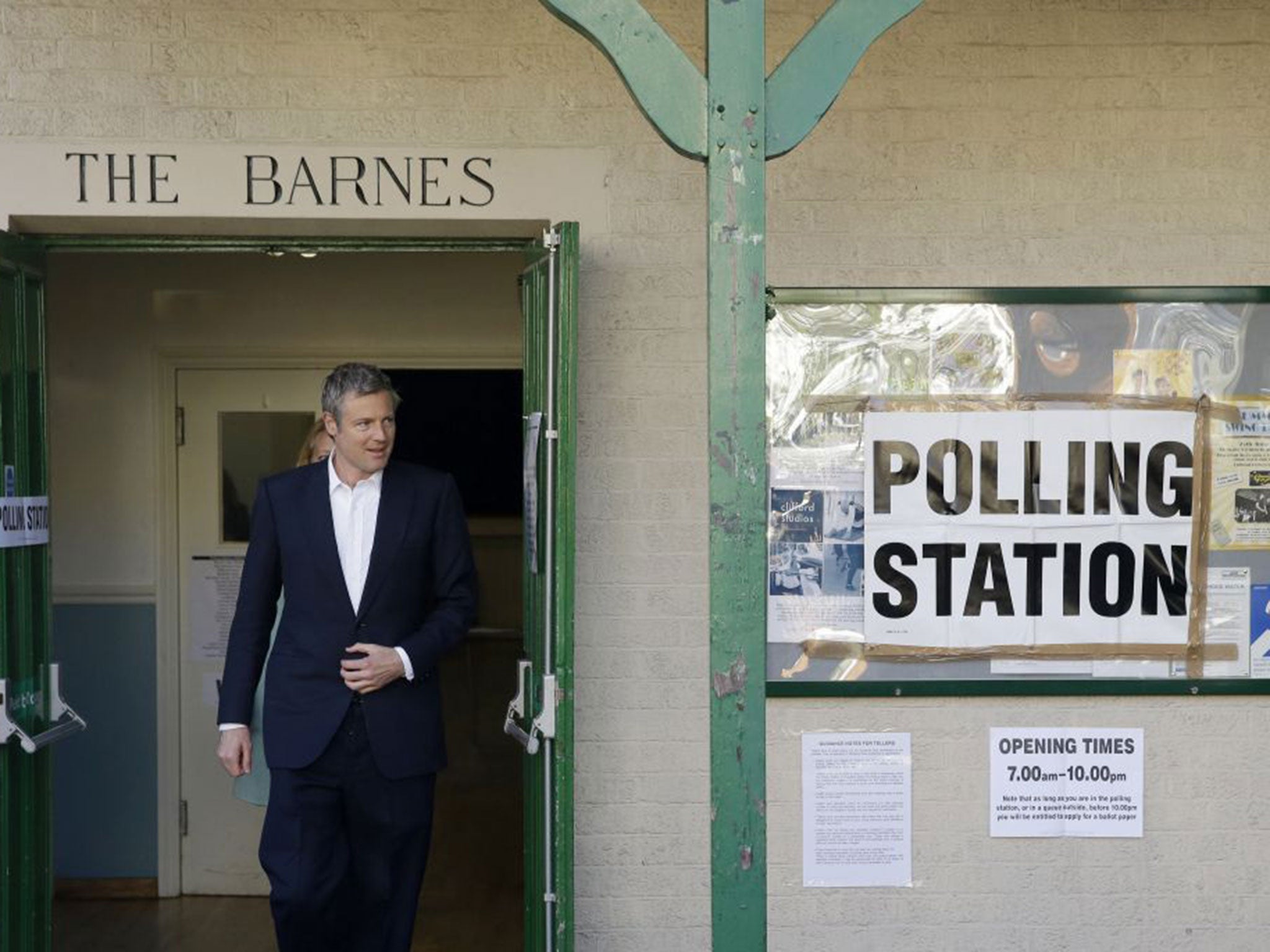

Late last year I signed up to help Zac Goldsmith campaign to be the next Mayor of London. I’d long been a fan of Zac: I thought he was sensible, principled, energetic — and frankly quite handsome. I’d followed his campaigns on direct democracy closely, and I liked his ideas about devolved planning. So I decided to dip my toe into party politics for the first time.

Six months later, my idealism has vanished. Goldsmith’s divisive campaign was a brutal wake up call. From early on, the fact that Labour’s candidate (and now Mayor), Sadiq Khan, was a Muslim played a central role in the Goldsmith campaign’s messaging. Crude letters were distributed to those with Indian, Sri Lankan or Tamil sounding surnames, accusing the Labour Party of wanting to tax their family jewellery. Voters were frequently reminded that, while Zac met Narendra Modi when he visited the UK, Sadiq, a Muslim, did not. In the last months of the campaign, any positive message was cast aside as the focus turned to Khan’s alleged links with anti-Semites, radicals and hate preachers.

Once, I mentioned the furore over the racial profiling of Tamils to one of the more senior people I sat near as a volunteer at the Conservative party headquarters. Instead of being frustrated or disappointed by the coverage, he explained to me that the controversy was a good thing. The message was getting out there, I was told; all publicity is good publicity.

What nonsense this turned out to be.

The scaremongering shocked every journalist, activist and campaigner who was once, like me, starry-eyed about Goldsmith. Peter Oborne called the campaign the “most repulsive” he had seen as a political reporter – more so than even the Bermondsey by-election of 1983, and the shameful General Election campaign in Smethwick in 1964.

Goldsmith always faced an uphill battle in London, especially after the capital was painted red last May. But his opposition was fundamentally flawed from the start.

Labour had embraced the divisive Jeremy Corbyn as leader, rejected Tessa Jowell for prospective London mayor and chose an aggressively bland candidate in Khan instead. Then they shot themselves in both feet just a week before the election with a row over anti-Semitism that saw the former Labour London mayor hiding in a disabled toilet, appearing to defend Hitler’s early years.

Zac Goldsmith may have been yet another white, male Etonian – a difficult starting point in a climate where inequality is considered as big a social evil as poverty – but he was not doomed to failure. Many voters who were instinctively anti-Conservative could have been won over by a positive campaign – one that emphasised his green credentials, his belief in direct democracy, his plans for house building.

Yet his operation focused on fear and forced even lifelong Conservatives into the arms of Khan.

Fear is a powerful motivating factor and, in politics, it can work. Fear of an SNP-Labour axis in Downing Street turned fence-sitters into reluctant, ‘shy’ Tories last May. It was fear of the alternative that pushed a lacklustre No campaign to victory in Scotland, and the same fear will prove crucial in persuading sceptical Brits to stay in the EU.

But fear only works if there is something to be afraid of. London – the most multi-cultural, international city in the country – is quite rightly not afraid of Muslims. And it is certainly not afraid when the Muslim in question is a centrist human rights lawyer who voted for same-sex marriage.

The Conservative Party’s innate desire for power is a good thing. It means that – with notable exceptions – it is rarely torn apart by the factionalism so common within Labour. But the brutal electoral tactics it deploys to this end can leave a bitter taste in the mouth.

It doesn’t really matter that Zac Goldsmith can’t hold a pint, knows bugger all about Bollywood or football, and was, for a bizarre five minutes, jokingly rumoured to be the “Croydon Cat Killer”. These were unfortunate but forgivable blips. Running a campaign that draws ready (and ideologically coherent) support from the likes of Katie Hopkins is harder to excuse.

I stopped volunteering for the Goldsmith’s campaign a month or so before the election. It wasn’t an entirely high-minded, principled departure: I had a dissertation to write and exams to prepare for. But I’m glad I got stopped when I did. It has been dismaying to watch an ostensibly modern, liberal Tory brought low in a campaign that will become a byword for dog-whistle politics.

As Baroness Warsi put it, this is not the Zac Goldsmith I know.

Fundamentally, I still think Zac is a good, decent man. I’d like to believe that he’s as unhappy as I am with the campaign to which his name became attached. But there is no denying that his messaging appealed to the basest instincts of the electorate, and he went along with it.

Zac Goldsmith lost resoundingly – and he deserved to.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments