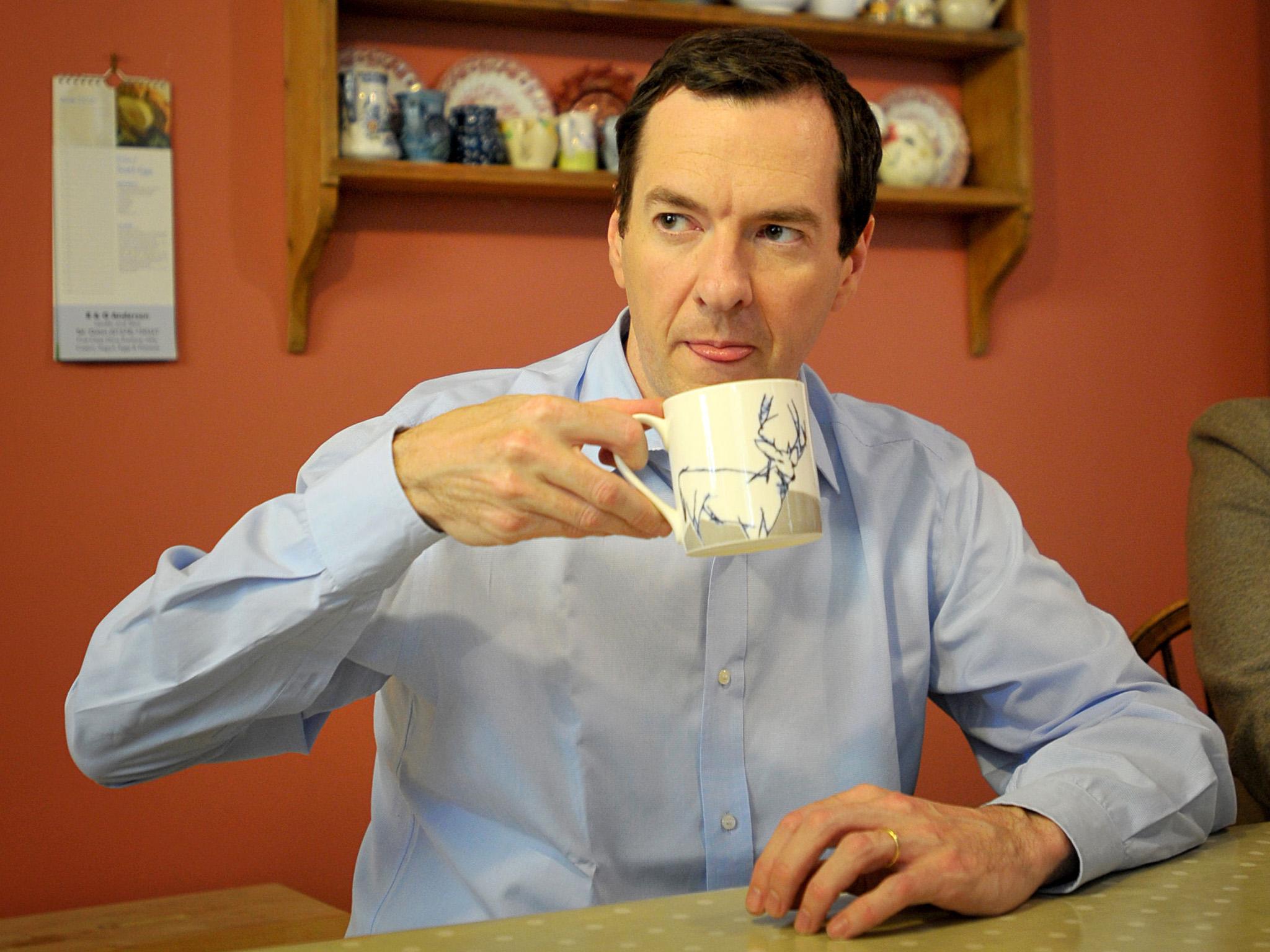

Would Osborne's promised 'emergency Budget' actually materialise after Brexit? I very much doubt it

A simple look at the maths - and political logic - shows how a budget of the kind he's threatened really wouldn't make any sense

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are told by both the present Chancellor and his predecessor that if we vote Leave there will be an emergency austerity budget to plug a £30bn “black hole” in the government’s finances. Measures could include an increase in income and inheritance tax and a cut in spending on the NHS, pensions and other areas.

Scary? Yes. Real? Well, I don’t see how it could be. Let’s follow through the logic: the maths first, and then the political reality.

The maths is straightforward. Osborne and Darling start with the hit to public finances from the slower growth that is projected to happen if people did vote to leave. There is general agreement that there would be some negative impact, if only because of the uncertainties that leaving would inevitably generate. There is less agreement as to how serious this might be. But the Institute for Fiscal Studies puts the hit at between £20bn and £40bn a year by 2019/20. Since the IFS occupies the nearest slot to sainthood as a commentator on UK public finances, let’s accept its numbers. If you take the mid-point of its range, there is indeed a £30bn-a-year hole.

You can fill that in one or both of two ways: higher taxes and lower spending. Osborne and Darling's idea is that you split it 50/50, raising an extra £15bn and cutting £15bn off spending. In theory putting the basic rate of tax up to 23p and the higher rate to 43p, plus IHT to 45 per cent, and an extra 5 per cent on alcohol and tobacco would get you there. As for the £15bn off spending, you would have to unprotect the protected departments, because you couldn’t do enough by squeezing the unprotected ones yet further.

So that is the maths and, as far as that goes, that is fine. The trouble is that in the real world this is not what a chancellor would do. It is not what either Mr Darling or Mr Osborne did when faced with unexpected financial pressure. In the case of Alistair Darling, he inherited unrealistic forecasts of the deficit. To his great credit (and in face of the fury of his predecessor, now Prime Minister Gordon Brown), he first insisted on having those forecasts restated, and then insisted on proposing a slow and measured correction of the deficit. He also acknowledged that it would take two parliaments to get back to balance.

In the case of George Osborne, he initially wanted to clear the deficit in one term. When growth slowed he eased up on that programme, ending up with a debt-reduction profile close to that initially proposed by his predecessor. That, surely, is what his successor (he would of course be out of office) would do. If the economy is slowing, you ease up on fiscal consolidation; you don’t knock the economy on the head.

So what would really happen? It is very simple. The deficit-correction programme would be pushed back by two years. In round numbers the deficit is being cut by just under £15bn a year; more in a good year, less in a bad – and there was a rise in 2012-13. That gradual correction is thanks to the natural buoyancy of revenue as the economy grows, and continued discipline over spending. You can have a debate as to whether this is the right pace, the right balance between spending and tax increases, the right priorities for spending, and the right tax policy. But this is what has been achieved. If the deficit was closed more slowly, that would mean a higher interest rate bill for the total national debt would be higher. But very low rates at present are containing the cost of that. There would also be some savings made from cutting net payments to the EU, perhaps £8bn a year. So that would help too.

The maths of Osborne and Darling are probably more or less right, then, but their projected policy response is quite wrong. It would not happen. Indeed, the more likely response to a Brexit-induced slowdown would be an easing of fiscal policy, not a tightening. As Vicky Redwood, chief UK economist for Capital Economics, put it in a note yesterday: “Overall, these claims look like a bit of a panicked reaction to the recent narrowing of the opinion polls; we think that the Government’s response would be far more measured than this.”

Actually Capital Economics think that if there were a good post-Brexit trade deal with Europe, the public finances might well correct of their own accord.

None of this means that Brexit would be positive for public finances. On the balance of probability it would be negative. But you have to put it in perspective. In 2009/10 the deficit was £154bn. Last financial year (the one that ended in April) it looks as though it will turn out at about £74bn. This financial year it is projected to fall to £55bn. In the context of these numbers, an extra £30bn blow would be bad news, but not a catastrophe.

The EU referendum debate has so far been characterised by bias, distortion and exaggeration. So until 23 June we we’re running a series of question and answer features that explain the most important issues in a detailed, dispassionate way to help inform your decision.

What is Brexit and why are we having an EU referendum?

Does the UK need to take more control of its sovereignty?

Could the UK media swing the EU referendum one way or another?

Will the UK benefit from being released from EU laws?

Will we gain or lose rights by leaving the European Union?

Will Brexit mean that Europeans have to leave the UK?

Will leaving the EU lead to the break-up of the UK?

What will happen to immigration if there's Brexit?

Will Brexit make the UK more or less safe?

Will the UK benefit from being released from EU laws?

Will leaving the EU save taxpayers money and mean more money for the NHS?

What will Brexit mean for British tourists booking holidays in the EU?

Will Brexit help or damage the environment?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments