The world's economic crises are entering a political stage – and the results could be dangerous

Historians found that the destruction of the middle classes was crucial to the rise of fascism, communism and militarism after the Great Depression. We must not allow history to repeat itself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In nature, phase transitions describe changes in states of matter. Depending on temperature, H2O can exist as solid (ice), liquid (water) or gas (water vapour). Societal crises behave similarly. Today, our economic problems have morphed into their social and political phases.

The economic issues are well understood. Growth is flagging. Inflation is low. The attempt to boost economic activity using debt and financialisation has created a large debt overhang which is proving intractable. Productivity improvements have decreased. Growth in trade and capital flows, which underpinned rising prosperity, is slowing. Entitlement systems, which assumed strong growth and different demographics, are now compromised.

Following the economic crisis of 2008, government debt levels in many advanced economies rose as governments sought to rescue the financial system and boost demand. The cure – in the form of old-fashioned pump-priming, interest rate cuts and more unconventional monetary policies (QE and negative interest rates) – have not dealt with the underlying pathology of the problems. There are side effects, such as inflated asset values and financial system weaknesses.

The economic problems have exposed long-standing social issues. Concern about employment, especially the quality of jobs, and stagnant incomes has created a backlash against globalisation and trade. Retrenchment of social services has affected living standards.

Housing affordability has declined due, in part, to inflated property values resulting from excess liquidity. Savings and retirement plans in many countries are threatened by low interest rates on safe investments. Inequality and concentration of wealth has risen.

The problems have now entered the political phase. Policy responses place a disproportionate share of the adjustment on the less affluent and the aged. High youth unemployment and rising education costs mean diminishing opportunities for the young. The inability of governments to deliver on promises to restore growth and prosperity in return for sacrifice has also become apparent.

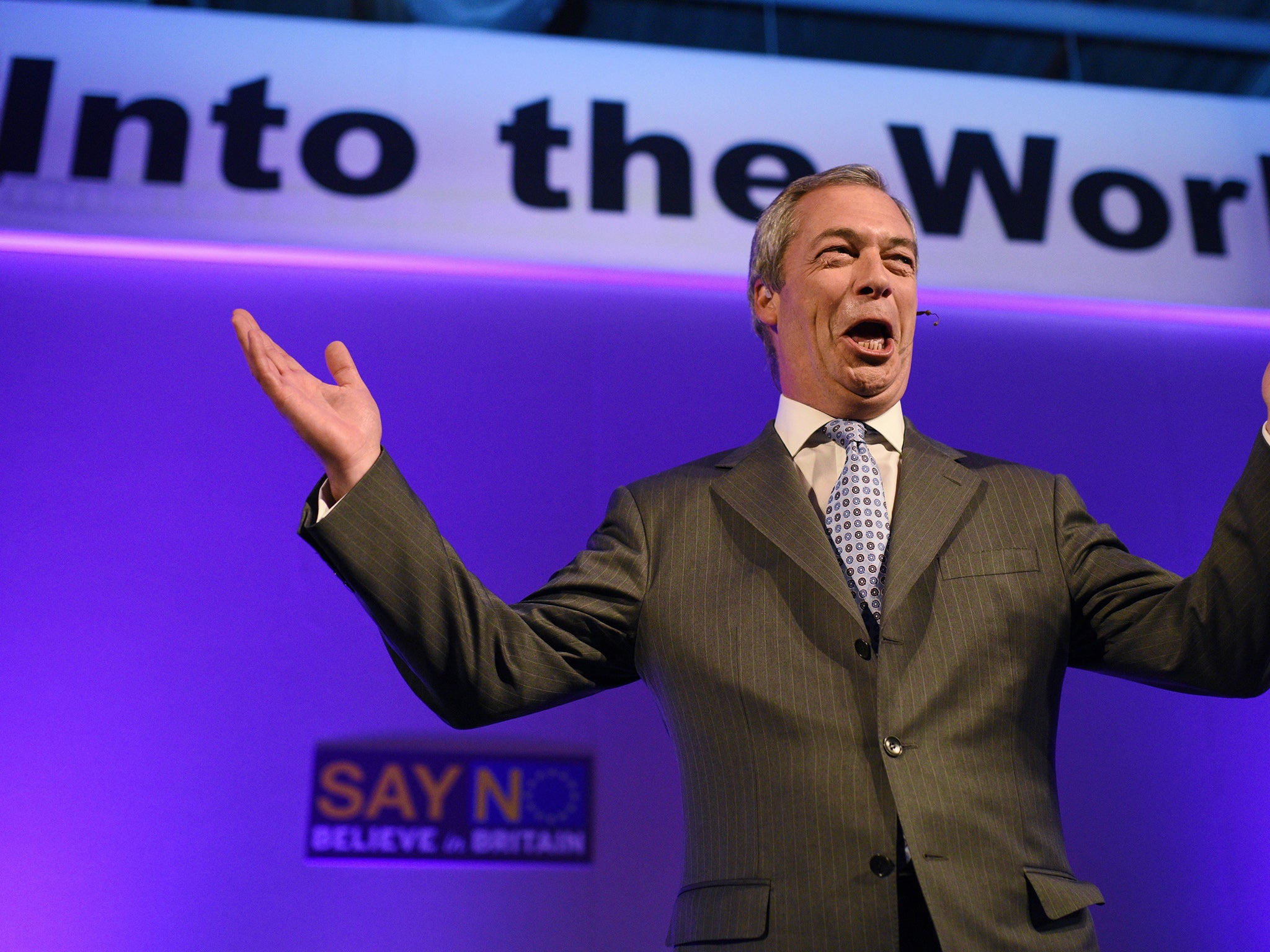

The rise of populist movements, and the growth of nationalism and xenophobia in many countries, reflects this dissatisfaction. Brexit is symptomatic of these pressures.

In the coming months, these same forces will inform a number of key events. It will be the background to the US Presidential election, where the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have channelled these concerns in different ways.

Italy is scheduled to hold a constitutional referendum in October 2016. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, already under increasing pressure from the anti-EU Five Star party, has threatened to resign if his reforms are rejected. A long running banking crisis also imperils the government. The EU bank regime requires the write down of debt which would result in politically damaging losses to small investors. But, if the Italian government moves to support banks directly, it will come into direct conflict with the EU.

Spain has not had a government since December 2015, after two elections as a divided electorate has failed to deliver a clear mandate. Elections are scheduled for 2017 in Germany and France, where far-right parties have tapped into discontent to increase their support. A number of Eastern European nations plan plebiscites on immigration which will exacerbate the EU’s internal divisions.

Even if they are unlikely to gain power in their own right, far-right and left political parties or movements are reshaping agendas. Ukip (which, remember, has only one elected member in the House of Commons) was influential in the EU referendum. Facing a voter backlash, mainstream political parties are being forced to alter policies on public finance, trade, immigration, international coordination and national sovereignty.

The political reaction to Brexit is revealing. There are suggestions that legal and parliamentary stratagems should be used to negate the result of the UK plebiscite.

Politicians argue that a complex question had been reduced to absurd simplicity. A simple majority of those who voted was too low a bar. Important decisions should not be for voters but left to informed elected officials and experts to avoid bad choices. There are proposals that only people who meet some minimum standard should be permitted to vote. (For the record, 36 per cent of eligible voters voted for leaving – a level higher than the vote required in recent years to gain the most powerful political position on the planet: the US presidency.)

Repression to supress rising dissent is reckless. Politicians must tackle the deep seated problems in the economic and social system. They must deal with large portions of the population who fear for their own and their children’s future. They must address the concerns of angry citizens who feel humiliated, ignored and uncertain of their identity.

As Winston Churchill observed, democracy, while far from perfect, is the worst form of Government except all other alternatives that have been tried.

In nature, there is a fourth stage of matter – plasma – which occurs at very high temperatures. It can be unstable and deadly. Political crises, if not managed, can similarly become dangerous.

Examining the Great Depression, historians found that the destruction of the middle classes was crucial to the rise of fascism, communism and militarism. Disaffected ordinary people who had lost their jobs, savings and hope turned to populist demagogues for salvation.

Politicians and policy makers in advanced economies must be careful not to repeat this history.

Satyajit Das is a former banker. His latest book is 'A Banquet of Consequences', published in North America as 'The Age of Stagnation'. He is also the author of 'Extreme Money' and 'Traders, Guns & Money'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments