Why replacing humans with robots will never work

Whether it’s self driving trains or touchscreens in McDonald’s, when a worker is demanding better pay and conditions suddenly everyone loves technology, writes Phil McDuff

Whenever we get strikes, a peculiar thing happens. People who, the rest of the year, can be found Googling “how do I open pdf” suddenly become techno-optimist futurists. Whether it’s self driving trains or touchscreens in McDonald’s, when a worker is demanding better pay and conditions, suddenly everyone loves technology.

Those techno-scabs tend to fall into two camps. The majority are simply wide-eyed naïfs who think technology is magic, who believe that if you hit an icon on your magic phone that your finger itself summons the Uber. These are people who neither know about nor care to understand the massively expensive technical infrastructure that underlies modern automation; or, for that matter, the highly paid technical staff who are required to keep it running.

Then there are those who do understand that automation is not a free lunch, who know it’s expensive and complicated and comes with its own set of trade offs, but who run entirely on spite and are prepared to pay any amount of money in order to not let workers win. They understand well that strikes are a conflict over power in the workplace, and what’s important to them is retaining the power to dictate terms and conditions to workers.

There is, of course, nothing new under the sun, and this conflict has been around as long as capitalism. Two hundred years ago, early in the industrial revolution, a group called the Luddites were smashing up weaving machines across England. Their name lives on in infamy as people who are opposed to, or just don’t understand, new technology and the advantages it brings.

But Jathan Sadowski, senior research fellow in the Emerging Technologies Research Lab – and self-described Luddite – says this is a case of history being written by the victors. Luddism, according to Sadowski, was not mindless opposition to technology and progress for its own sake. Rather “the Luddites wanted technology to be deployed in ways that made work more humane and gave workers more autonomy.” But they lost – the Luddites were defeated, shot and hung, and “their story is told to discourage workers from resisting the march of capitalist progress.”

The conflict over automation and mechanisation is very rarely one of simple opposition to technology for technology’s sake, but a dispute about who owns, controls, and benefits from technology.

Consider what would happen if, tomorrow, an inventor was to create a flawless robot that could replace human workers in all dangerous, tedious labour. In a sane world that inventor would go down in history as a hero, the architect of a golden age.

But we do not live in a sane world, we live under a capitalist system in which the spoils of automation accrue to a very few rich people at the top of society, and so that inventor would instead be remembered as one of history’s greatest monsters, responsible for mass immiseration, riots, starvation and poverty as millions – perhaps billions – of people were rendered unemployed overnight. The robots might be able to take over in the farms and mines, but ironically the farm and mine owners would no longer have any customers to sell to.

Automation under the control of workers is good. I’ve automated parts of my own job to save time and free myself from repetitive drudgery. But under capitalism, automation rarely simply abolishes the need for human labour, giving us time for leisure and our own needs, but instead moves and transforms it – from weavers to machine operators, from drivers to server administrators.

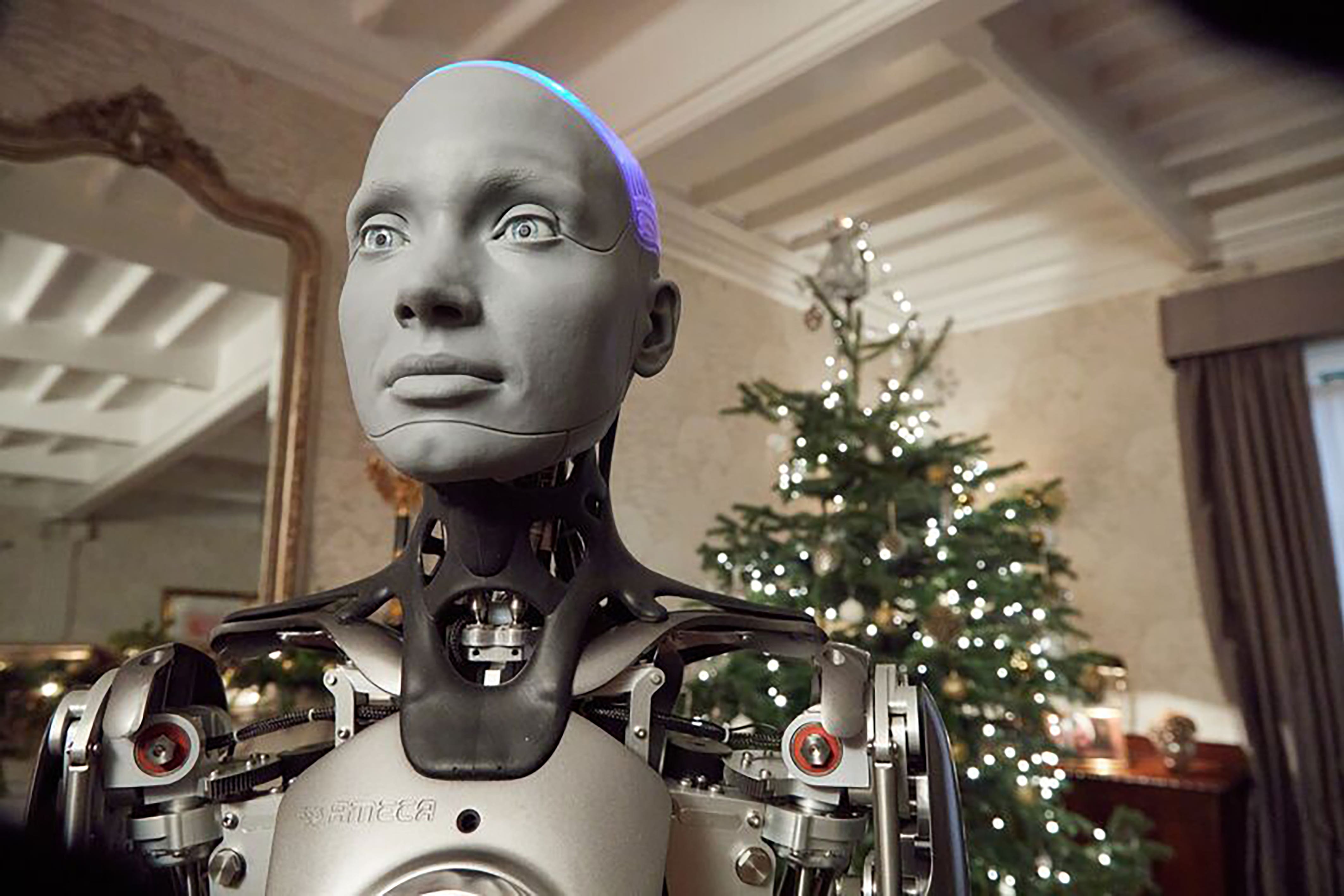

Even art is being pulled into the sphere of technological automation, as new “artificial intelligence” models purport to be able to perform the work of artists based on a few text prompts – as long as you don’t ask them to draw hands. But “AI” models rely on the unseen labour of millions of “crowdworking” humans across the globe tagging and categorising the data to make it comprehensible by the machines, often under low-paid, exploitative, precarious contracts.

To the extent that we work fewer hours than our Victorian forebears, this isn’t down to us needing fewer hours of work to create the basics of human necessity (even though that’s true). Rather, it is due to the militant actions of organised labour in winning concessions from the owner class – in wresting the undeniable benefits of automation from the mill and factory owners and distributing them across the workforce in the form of weekends, paid sick leave and the like.

Technology has improved our productivity by orders of magnitude since the days of the Luddites, but one fifth of the population in the UK lives in poverty today. Tech won’t save us if the social and economic conditions it is deployed in are still based on exploitation and precarity.

In the UK the threat that “we’ll automate your jobs” is mostly hollow, especially in transportation. It is, in fact, still difficult to automate all aspects of a train driver’s job reliably and safely, and errors do not result in weird drawings of fingers, but in derailments and fatalities.

Where it has been achieved, it has been on isolated networks like the DLR, and even then humans are still needed as a failsafe. But even if the technology were to advance to the point that a machine could safely drive a high-speed train from London to Manchester without human supervision, the UK government is incredibly unlikely to commit to the hundreds of billions of pounds that would be required to make it work. We haven’t even fully electrified the rail network yet.

We’re decades away – at best – from the kind of infrastructural improvements that would be needed to make automation work. Rail workers on strike today will likely be retired before any automation plans get implemented by this penny-pinching government and its corrupt army of thieving, useless contractors.

Ironically, the best way to improve technology and infrastructure is to do it in collaboration with the workers who use it, and who can guide the development of new technologies in a way that makes sense, rather than the kind of pointless antagonism that leads bosses and governments to rely on hucksters and con-artists who promise the moon on a stick and deliver nothing but invoices.

But nobody threatening workers with robot strike breakers actually wants or believes in a technologically advanced future. They want a cowed and subservient workforce, held in place by the threat of poverty if they dare step out of line.

The Luddites were not defeated because automation simply left them in the dust. They were killed. And if the rail strikes are defeated it won’t be because magical automation renders the “overpaid dinosaurs” obsolete, but because the government has decided that worse, less safe, less reliable service is a price worth paying to avoid workers having more control over their own jobs and conditions.

They’ll sell us a techno-future of robot trains and strike-free travel, but what they’ll deliver is a broken-down, disconnected network of ageing trains and cracked rails that we can’t afford to use.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments