I was the wrong colour to perform at the London Olympics – acting is still run by the white middle classes

‘Colour-blind casting’ has made it hard for white male actors to find work, according to a former RSC boss. But such an innovation might have saved my stage and screen career, writes Nicholas Beveney. To earn a living, I had to leave the country – a decision I took when I lost my starring role in the 2012 opening ceremony

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Gregory Doran, the former artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, said acting is now “difficult” for white male actors – and that, in an era of colour-blind casting, they are now “finding themselves with very little work” – it hit something of a nerve with me.

In fact, as someone who has worked as a Black male actor, it struck me as one of the most dangerous statements ever made by someone with connections to one of the most important theatre companies in the UK.

That Doran has only said such things now – how giving more opportunities to underrepresented groups has meant people who traditionally dominated theatre were now “finding themselves with very little work”, and how he hoped the “pendulum will swing” – when he no longer holds a mantle for the RSC, speaks volumes. It also gives an insight into the mindset of the predominantly white middle class that still runs British theatre.

Looking for a response to Doran’s comments, I kept coming back to one word: verisimilitude. That there appears to be something in whatever has been stated as fact – but, in fact, it’s far from the truth.

In that same interview, Doran was keen to point out that he had cast the first disabled actor to play Richard III, cast female actors as male characters in Troilus and Cressida, and introduced the RSC’s first season of female-only directors. But it was all a bit “my best friend is a Black woman in a wheelchair” for my liking.

Great iniquities were highlighted by the Black Lives Matter movement, which was loud and taken by some as a threat. But companies – acting companies included – have been left in no doubt that they have a social responsibility.

The margins in the acting industry are small. I spent years getting by as an actor – appearing in hits such as Black Earth Rising with Michaela Coel, as well as the BBC drama series Noughts + Crosses and action film The Patrol – before moving into independent TV and film production. To do that, I had to leave the country, moving to South Africa to escape that very mindset within the industry that Doran has revealed.

As a young Black actor, there were only two people who ever took a chance on me. Almost 25 years ago, the legendary British director John Retallack cast me as Bottom in the Oxford Stage Company production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The wider acceptance of blind casting means that would hardly cause a ripple these days, but it shows he was forward thinking like that. He loved thinking out of the box.

The second was David Thacker, a crazy genius and one of the best directors I’ve ever worked for. In 2007, he cast me in Waking the Dead, giving me a part that had been written for a white actor. “But we can let that guy be Black!” he said.

These two occasions when my skin colour didn’t hold me back as an actor still stand out, because such moments have been so few in my entire career.

The majority of writers and creators in the UK are white, so inevitably it’s their lived experience that gets made into TV. They say you write about your surroundings and what you know, (and for audiences and commissioning editors that they know). So the circles they move in makes it difficult for Black actors. The problem is systemic.

With the arrival of social responsibility, things have got a little better. After all, Black audiences pay the taxes that fund the Arts Council, and we pay our BBC licence fee, too. Any improvement in representation has been one of economics.

But for a long time, I just wasn’t seeing scripts for stories that I’d love to be in. I also didn’t want to go to America and be a Brit in a US series. My real passion was for African cinema, which I have pursued with my own production company.

The moment I realised that, if I wanted to work, I’d have to leave Britain came at the London Olympics in 2012. I had been working with Danny Boyle on the opening ceremony. I was at my lowest ebb – there was no work – so had accepted a role as understudy (to Mark Rylance), something I’d never done in my career.

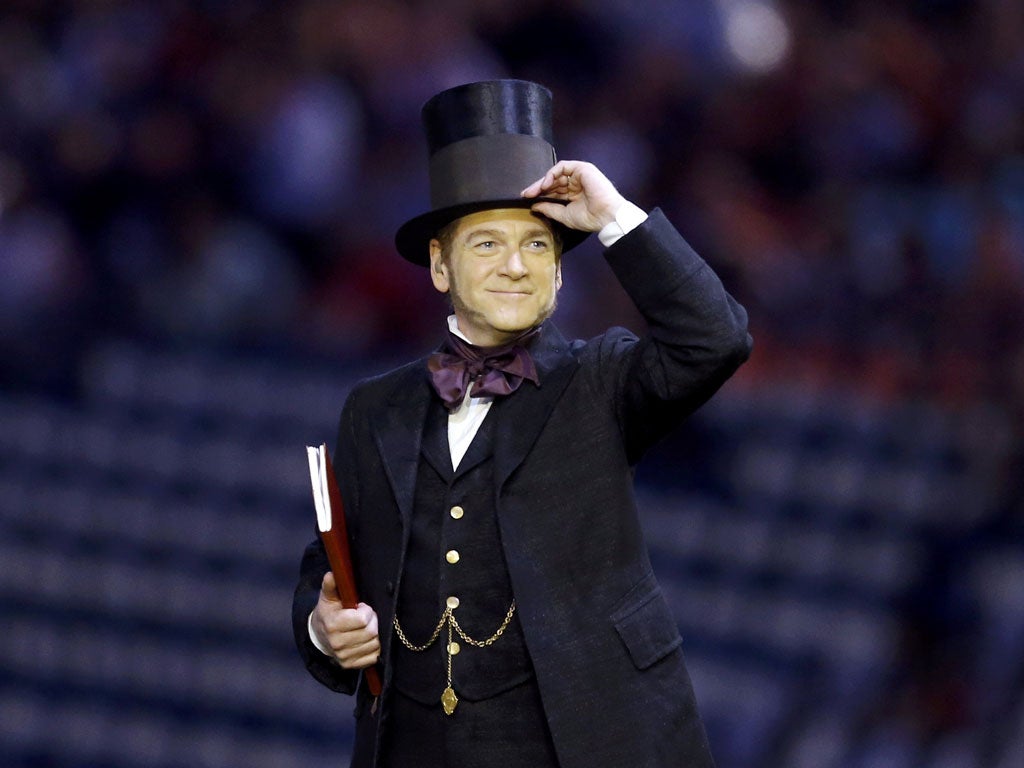

He was cast as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the Victorian engineer who is a focus during the Industrial Revolution section of the show. The part culminates with a reading of Caliban’s speech from The Tempest.

I did a couple of performances as Isambard, in the stadium, in front of a crowd. Then, just a few days before the opening ceremony, Mark pulled out.

Danny took me aside, and said: “So, this is where you play Isambard... except I don’t think the world is ready for you to play a white character. So I’ve called on my friend Kenneth Branagh instead...”

Maybe, in hindsight, he was right – that audiences weren’t ready for a Black Isambard. But it was the moment I decided to leave the UK.

Now, more than a decade later, we’ve got a Black Doctor Who, which is perhaps a sign that times are finally changing. It’s just a shame that some people in my industry don’t seem that happy that they are.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments