When it comes to politics, it's last impressions that matter most

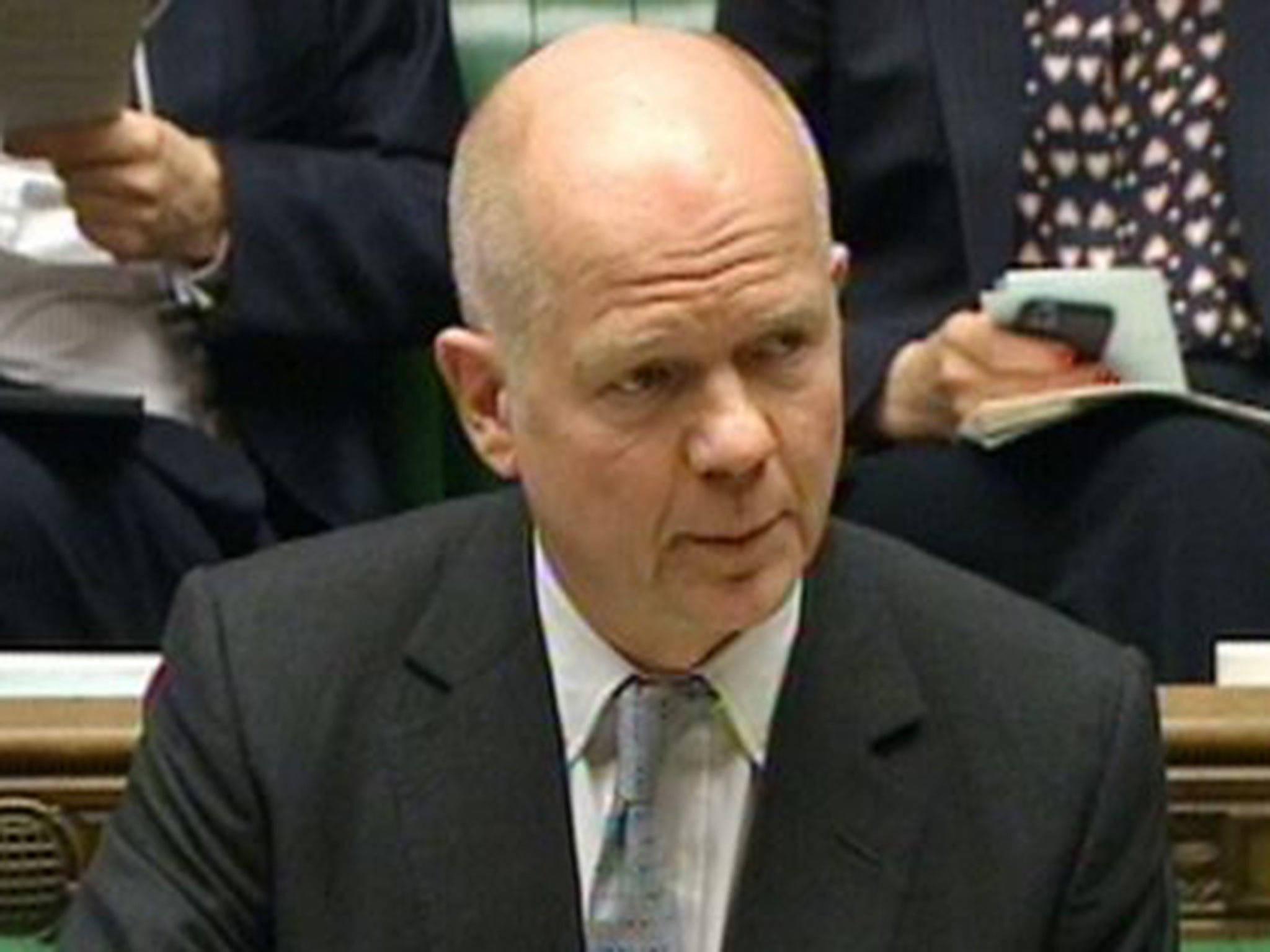

William Hague's final day as an MP showed little of the selfless dignity with which most politicians like to leave the stage

It was not, all things considered, the way he would have wanted to go. William Hague, Leader of the House, spent his last day in the Commons on Thursday, not in dignified leave-taking, but in trying to unseat the Speaker. Which was spirited of him, except he failed. John Bercow remains, notwithstanding Hague’s bid to make voting for Speaker a matter for a secret ballot, which would have made it much easier to vote Bercow, loathed by many Tories, out.

So, instead of ending on a high note, Hague was discomfited. It was his birthday too. His ambush failed – the vote was sprung on the Commons – and he was charged with being party to a “grubby plot” and “jiggery pokery”. His Labour counterpart, Angela Eagle, declared that he had brought the Commons to an “appalling situation”. And she had been so nice about him earlier in the week.

So, Hague went out plotting and fighting rather than as dignified elder statesman – he’s a bit young for that. That’s one way of taking leave of office. And leaving office is an art in itself. It’s the last image that’s the most abiding, the equivalent of the aftertaste in the mouth which depends on the last thing you ate at dinner. That picture of Margaret Thatcher after her resignation – leaning forward from the back of her car, the kept-back tears shining in her eyes – was the one that stuck with us: Mrs T in defeat, but putting the pluckiest face on things.

How you do valedictions depends on circumstance – whether you jump or are pushed – and on personality. At best, it’s the equivalent of the poise of the doomed Thane of Cawdor in Macbeth: “nothing in life became him like the leaving of it”, observed Malcolm admiringly. People said much the same about Gordon Brown. His political life, characterised by begrudgery, vengefulness and a sense of thwarted entitlement, ended on a note of magnanimity. “It was a privilege to serve... thank you and goodbye.”

Tony Blair’s resignation speech to his constituency was one of the most eloquent of his career – ostensibly humble, but actually a resounding vindication of his record. It ended gracefully: “I give my thanks to you, the British people, for the times I have succeeded and my apologies to you for the times I have fallen short. Good luck.”

Beautifully done. Trouble was, the last thing we remembered about the Blairs leaving Downing Street was Cherie Blair’s parting, chippy shot at journalists. “Goodbye. I don’t think we’ll miss you.”

What you want is to leave office or position either on a high note, with people wanting more – think Mary Poppins departing the Banks’ home, without a word of warning, on an umbrella – or in a fashion that does the most damage to those you want to wound.

Few people remember much about Geoffrey Howe in office except his resignation speech, but that brought down Mrs Thatcher – and it was all the more devastating for being ostensibly without rancour. It ended: “I have done what I believe to be right for my party and my country. The time has come for others to consider their own response to the tragic conflict of loyalties with which I myself have wrestled for perhaps too long.” The next day, Michael Heseltine stood against Mrs Thatcher.

Robin Cook’s parting speech, delivered from the back benches during the debate on the Iraq war, was no less effective. It was a comprehensive rebuttal of the case for war and it ended: “I intend to join those tomorrow night who will vote against military action now. It is for that reason, and that reason alone, and with a heavy heart, that I resign from the government.” It brought the House down.

Indeed the critical thing about a decent political leave-taking is that it should be seen to be selfless – putting the interests of the nation before your own. It gives a redemptive aspect even to resignations that are obviously forced. Richard Nixon had stubbornly refused to resign in the wake of Watergate but he struck just that note when he finally delivered his resignation address: “I would have preferred to carry through to the finish whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so. But the interest of the nation must always come before any personal considerations.” But of course!

Probably the best valedictions are those that take everyone unawares. Bilbo Baggins’ valedictory speech on the occasion of his eleventy first birthday in a party of special magnificence at Bag End concluded: “This is the End. I am going. I am leaving NOW. GOOD-BYE.” And bang, he disappeared.

Few can quite match that, but Pope Benedict came close. It had been 600 years since a pope had last resigned but Benedict did so in an early morning consistory convened for quite another purpose. Moreover, he dropped the bombshell in Latin, which meant that the only journalist to pick up the news as it was delivered was a bright Italian girl. It confounded friends and enemies.

Hague’s very political departure from the Commons may point to the fact that this isn’t the last we’ll hear of him. He may return – to the Lords. That’s the other secret to saying goodbye – leave open the possibility that it is, in fact, only au revoir.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks