What's the real cost of better healthcare?

How much are we prepared to pay for medicines that only benefit a few?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are entering the era of personalised medicine. It was exemplified last week by a “milestone” trial of a new drug for prostate cancer that slowed tumour growth in 88 per cent of patients who were given it.

This was a small trial and these are early results. But a drug that is effective in nine out of ten patients is remarkable by any standards. Moreover, these were patients with advanced disease, in whom all other treatments had failed, who were not expected to live for more than 10 to 12 months.

The drug is called olaparib and was originally developed for ovarian cancer. It works in individuals with a specific genetic mutation by interfering with the mechanism that enables the tumour to grow – and, importantly, is common to both ovarian and prostate cancer.

This shows how we are going to have to rethink the way we talk about cancer. Rather than identifying cancers by their location – in the ovary or the prostate gland – we are going to have to learn to identify them by their dodgy genetics, the mutated DNA that gives rise to the malignant growth.

Take breast cancer. One in five women with the disease have a gene mutation, HER-2, that drives the cancer and can be treated with the drug, Herceptin. What used to be single diseases are being split into many – each (potentially) with its own targeted treatment. Using sophisticated diagnostic tests, patients can be matched with the right personalised therapy in place of the blunderbuss, one size fits all, chemotherapies, which fail to work in many patients.

If you are a scientist, this is heady stuff. If you are a cancer sufferer, it is grounds for hope. Moreover, genetic research and targeted therapies are not limited to cancer. New treatments for common conditions such as strokes, diabetes and Alzheimer’s are likely to follow.

But there is a problem. As the diseases are divided into their genetic types, the cost of developing personalised treatments will be spread over smaller and smaller groups of patients. If it cannot be re-couped from selling the treatment to thousands or millions of patients, it will have to come from elsewhere.

Olaparib costs £4,000 per patient per month. The National Council for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has already rejected it for ovarian cancer because it is too expensive. Undeterred, Cancer Research UK, which helped fund the prostate cancer trial, declared the results “exciting” and added: “The hope is that this approach could save many more lives in the future.”

That is the hope. But is it realistic? Consider cystic fibrosis which affects over 10,000 people in the UK. Genetic research has revealed that this too is not one disease but many. A number of gene mutations cause the clogged lungs and malfunctioning organs that are the distinguishing features of the condition. Now a US biotech company, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, has developed a drug Kalydeco that targets one of these mutations, shared by an estimated 270 people in the UK. Some are already being prescribed Kalydeco but the cost is eye-watering – £182,000 a year.

Is the sky the limit? It would appear so. The first $1m (£650,000) gene therapy was approved in Europe two years ago. Called Glybera, it is a treatment given by injection for an extremely rare blood disorder affecting a few dozen people in the UK. The average patient needs 19 injections at a cost of $50,000 (£32,000) each. The launch of the drug has been delayed, pending further data collection, but it is expected to reach the market in Germany this year and afterwards in Britain.

In 2006, there were barely a dozen drugs in the world with genetic prescribing information on their labels. Today there are more than 150. How to afford these drugs is already causing hand-wringing among Governments and regulators, wrestling with the measurement of “value”.

This is not just a problem for the NHS. David Blumenthal, president of the New York based Commonwealth Fund, has warned that it will also challenge our fundamental belief in providing care, free, on the basis of need. How much are we prepared to pay, collectively for very expensive medicines that benefit just a few? Sky high price tags could start to test our common bonds.

Optimists believe that these advances need not spell financial doom, because they may make care cheaper, by avoiding expensive medical and hospital costs for symptomatic treatments.

Super-optimists argue that the costs of health care overall are set to fall, thanks to smart phone technology which will allow us to monitor our health far more closely than at present, detecting diseases early when we can intervene more simply, effectively and cheaply.

Realists, however, need to start thinking now about the difficult choices that lie ahead.

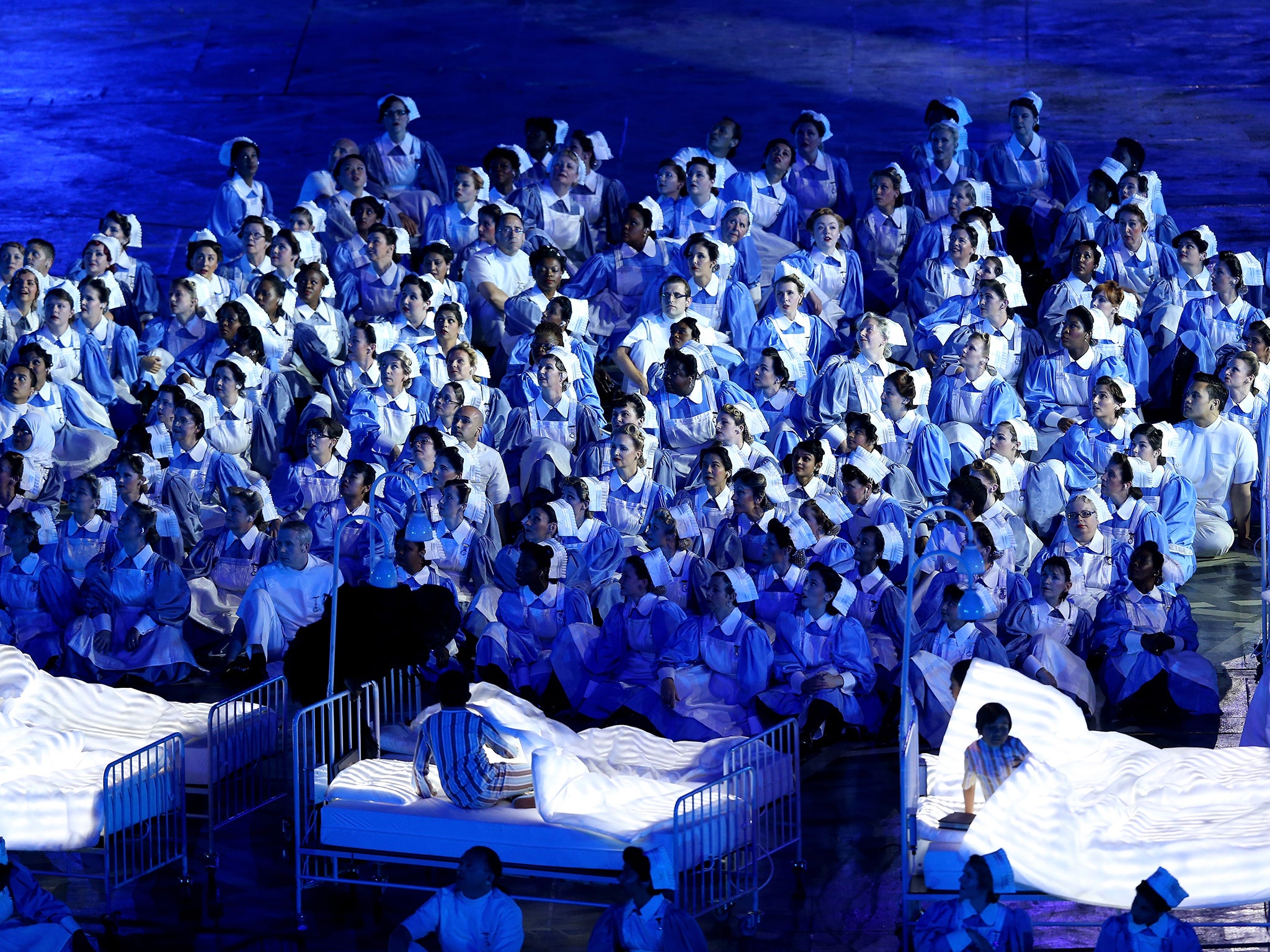

The NHS is revered throughout the world for providing modern, universal, free healthcare. If that care is no longer seen as modern or universal, the public mood could soon darken.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments