I had my skin colour and my identity taken away from me

Although I can’t change my past, I am grateful to finally know who I am

I’ll always remember just how awkward it used to be, how uncomfortable I’d feel, introducing myself to new people. “Sheetal, that’s an unusual name,” they’d often comment questioningly. “My parents were going through a hippy stage and gave me an Indian name,” I’d explain, before quickly changing the conversation topic.

They’d never ask anything else about it. Why would they? There was no reason to doubt what I was saying. Yet it was completely untrue. Because although my skin was pale, I am actually Indian. My mum was born in Zanzibar and my dad, from India originally, was brought up in Mombasa.

But a condition called universal vitiligo had stripped the brown pigment from my skin; something that had dominated my life for many years and had left me so lost and exhausted, I stopped correcting people when they assumed I was white.

And now we hear about ruxolitinib: a new treatment for vitiligo that can restore pigment to the skin. The prescription-only drug (which has some potentially serious side effects) might soon be offered on the NHS. But should it?

It was my sister, Tejal, who noticed the first patch of white skin behind my ear when I was seven years old. It didn’t hurt, or itch, or cause me discomfort; but over the years, more patches appeared and spread over my arms, face and legs. Luckily I wasn’t bullied, but my parents were anxious and took me to the GP. They identified it as vitiligo, but had no idea what it meant or if it could be cured.

And their worries only grew when relatives and family friends would tut when they saw me. “Is it leprosy or skin cancer?” they’d ask. “You need to do something.” Soon, my skin was becoming a matter of concern for everyone – even me. Then my parents heard of a clinic in India that had proven cases where they’d managed to shrink the white patches and bring back the brown skin. A family friend had sent their daughter and it seemed to be helping her.

I was excited at the thought of being “cured”, so I happily went with my parents to India. There I was prescribed numerous treatments. From sticking to a strict diet to putting oil on my white patches and sitting in the sun, I tried everything. The worst was having to scrape the dead skin cells off my body, then apply a paste. When you removed it, the skin underneath would burn. Mum or Dad would fan the area to cool it but the agony would last for hours.

Of course, vitiligo has no cure, so none of the treatments worked, no matter how often we went back. By the time I was 17, I was tired, stopped taking the medicines on time, even skipped them completely. Dad noticed and asked what was happening. I told him the truth. I couldn’t do this anymore.

I think it was a relief for us all. By 21, the vitiligo had spread so much I’d lost all of the pigmentation in my skin. “Surely that’s better, now that your patches are gone?” people would smile. But it didn’t feel like that to me.

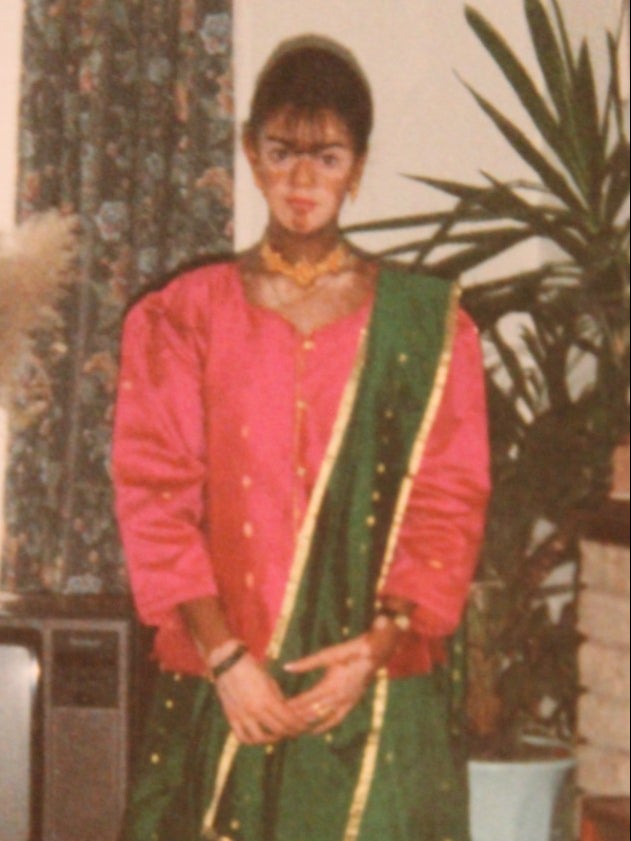

To the outside world, I looked white. But I wasn’t. I felt lost, like my whole Indian culture didn’t apply to me anymore. At family gatherings, I felt like I stuck out like a sore thumb. At Indian weddings, I’d hear people whisper how well the English woman had dressed herself in Indian clothing.

Even when I met my husband Ketan, who knew about my condition, I remained self-conscious. When Mum tried to show him pictures of when I was younger, I’d shut the photo albums firmly. When we got married and moved to Birmingham, everyone presumed I was white – and I decided to go along with it.

I got a job in banking, which often involved networking, meeting new people – and wearing a name badge. If anyone questioned my name, I’d brush it off or lie. Even at the time, I knew it wasn’t the right way to handle it but I couldn’t face more people knowing about my changing skin colour, asking me questions, looking at me differently.

I was acutely aware of my skin colour. Of how Indian women would look at me when I walked past with Ketan, as if I’d taken one of “theirs”. Of how white bouncers would only let my Indian relatives into a club when they saw I was with them.

When we had our two daughters, people at their school would often presume I was the nanny. It was only after seeing a documentary on vitiligo that it all came to a head. I realised that my experience with the condition had been so difficult because nobody talked about it – but I still wasn’t talking about it.

Plucking up my courage, I showed my husband a picture of my teenage self, complete with vitiligo patches. He was astounded when I told him about how traumatised I still felt about it. Then I decided to post the same picture on social media, with a short explanation of what I’d been through. The response was amazing. “We didn’t realise you were so upset,” friends from school messaged me. For years, I’d hidden it so well.

From then on, I slowly began to open up, joining various vitiligo charities – including Vitiligo Society – and support groups, and posting different pictures of me through the years on Facebook. I was in awe when I first saw Winnie Harlow. I wish I could have had her confidence.

But although I can’t change my past, I am grateful to finally know who I am. Vitiligo and my skin colour has dominated so much of my life, but now I know my identity is far more than just skin deep.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks