We are still paying the price of Boris’s Brexit blunders – and now the union is in peril…

Sinn Fein is right, writes Andrew Grice, a united Ireland is in touching distance as the party’s vice-president Michelle O’Neill prepares to become Northern Ireland’s first minister

Rishi Sunak has cleared up yet another bit of Boris Johnson’s mess. The deal announced in the Commons today to reduce checks on goods going from Great Britain to Northern Ireland could and should have been part of Johnson’s Brexit deal. Incredibly, the then-prime minister either didn’t understand the detail, as one senior civil servant told me at the time, or knew he was creating a trade border in the Irish Sea while lying about it.

Indeed, the whole of the UK is still paying a price for Johnson’s threadbare EU deal. Checks on imports of plant, meat and other animal products from the EU, which have been delayed on five occasions, finally take effect today – exactly four years after Brexit. There could be higher prices and shortages in supermarkets as a result.

Another Johnson triumph. Sunak doesn’t have the strength in his own party to clean up that disaster, even though it harms the UK economy. The job will likely fall to a Labour government, which would align with EU rules.

Sunak and Chris Heaton-Harris, the Northern Ireland secretary, deserve credit for persuading the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to return to the power-sharing government – a year later than they hoped when Sunak finalised his Windsor framework with the EU.

The DUP’s wheels always turn slowly, and the party’s two-year boycott of the province’s assembly and executive has damaged it. The DUP dinosaurs also harmed themselves by supporting Brexit, which the people of Northern Ireland voted against. Cosying up to the Conservatives did the DUP no good – Johnson betrayed them.

Its leader Jeffrey Donaldson had to win some concessions to outmanoeuvre hardliners inside a party that sees betrayal around every corner. Donaldson is understandably bigging up tweaks that will reduce customs checks and allow Northern Ireland to benefit from future UK trade deals.

Although Donaldson claims there will be “zero checks, zero customs paperwork” on goods moving within the UK, the package appears to fall short of his original demands.

But once the Commons had approved the Windsor framework, he was never going to achieve them. The tweaks should be enough to see off his DUP critics. But, just as the DUP supplanted David Trimble’s Ulster Unionist Party after it signed the Good Friday Agreement, the DUP might now be outflanked by hardliners such as Traditional Unionist Voice.

Donaldson’s eventual move took courage, but he was right to restore self-government. Northern Ireland’s public services are creaking after the two-year hiatus, and the UK government’s inevitable £3.3bn bung won’t solve the backlog of problems, notably on public sector pay.

For Sunak, the move is not without risk. It could create another front in his battle with his own right-wing critics, already furious that his Rwanda scheme is not tough enough and his proposal to raise the legal age for smoking is “unconservative”. Eurosceptic Tories fear the DUP deal will prevent the UK from diverging from EU regulations, which Johnson’s hard Brexit is supposed to allow. Ministers insist the UK still has the right to diverge, but the DUP agreement makes it even less likely they will use it. As on Rwanda and the Windsor framework, the threat of a right-wing rebellion will probably fizzle out.

The deal will not end the threat to the UK’s survival in its current form. Donaldson judged that not having a functioning devolved government would undermine the Union by building support for a united Ireland. But his strategy is a gamble. As Sinn Fein won the most seats in the last assembly elections, its vice-president Michelle O’Neill will become first minister later this week, the first time the post has been held by a nationalist – a highly symbolic moment. Sinn Fein could also win Ireland’s forthcoming election; it currently tops the opinion polls there. Its chances in the south will be boosted if O’Neill governs responsibly in the north.

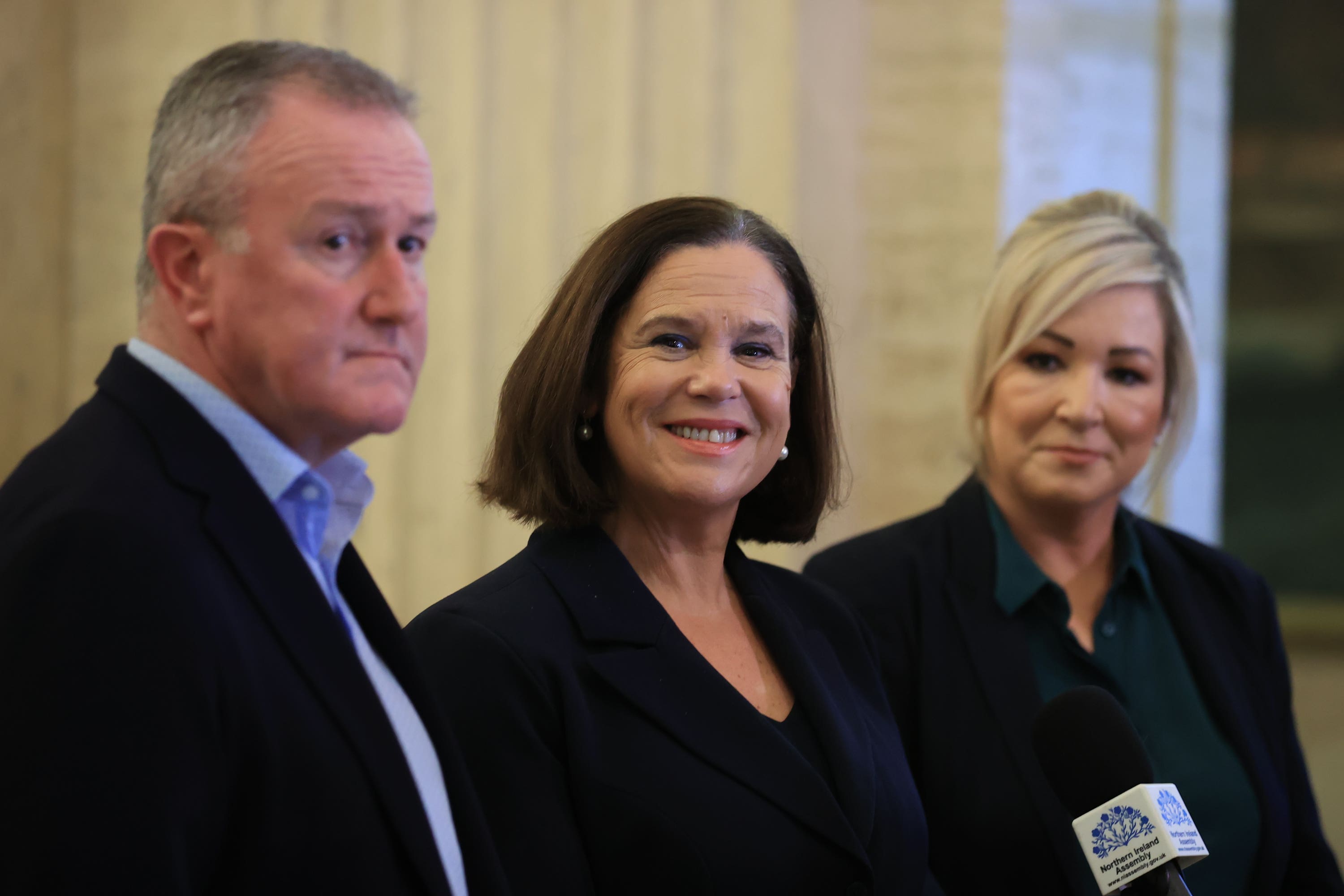

Holding power on both sides of the border would put the issue of a united Ireland firmly on the agenda. Mary Lou McDonald, the Sinn Fein president, says the restoration of power-sharing in Northern Ireland has brought it within “touching distance.” Her goal of a border poll on unification in both countries by 2030 no longer looks such a remote possibility. The UK government is committed to holding one if there is consistent public support for it in the north. Although unionist parties collectively hold more seats than nationalists in the assembly, a period of stable Sinn Fein-led government might change that. The long-term prospect of a united Ireland could become a medium-term one.

Similarly, the SNP’s turmoil should not mask that support for an independent Scotland remains at about the 45 per cent level seen at the 2014 referendum.

Labour might be riding high now, and should gain 20 Scottish seats at the general election. But Labour insiders admit privately that if the party regains power at Westminster, it would have to work hard to stop nationalists building support for independence through “grievance politics,” as they did when Labour was last in office.

The fight to save the Union is far from over. It has only just begun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments