The EU's decision to categorise Uber as a taxi company shows how old-fashioned it is

Like with Google, Facebook and Amazon, the bureaucrats and the lawyers are finding it much more difficult to deal with these new disruptive technologies than consumers

Once upon a time Luddites were easy to identify. The original early 19th-century machine-breakers, fearful that new technology would destroy their jobs and lives, went around in rough workers’ clothes and left slogans behind about their fictional leader “Ned Ludd”, “Captain Ludd” or “King Ludd”. Later on these forces of industrial conservatism evolved into trade unions, and were recognised, and feared, at the very mention of their titles – “shop steward”, “convenor”, “general secretary”.

All that has now passed into irrelevance, their grim warnings and anxieties replaced by centuries of capitalist progress. Today, though, we have new Luddites: bureaucrats dressed in smart suits or lawyers in judicial robes, all highly educated and eloquent, but all the direct spiritual descendants of the guys who roamed the countryside of England smashing textile machines a couple of centuries ago.

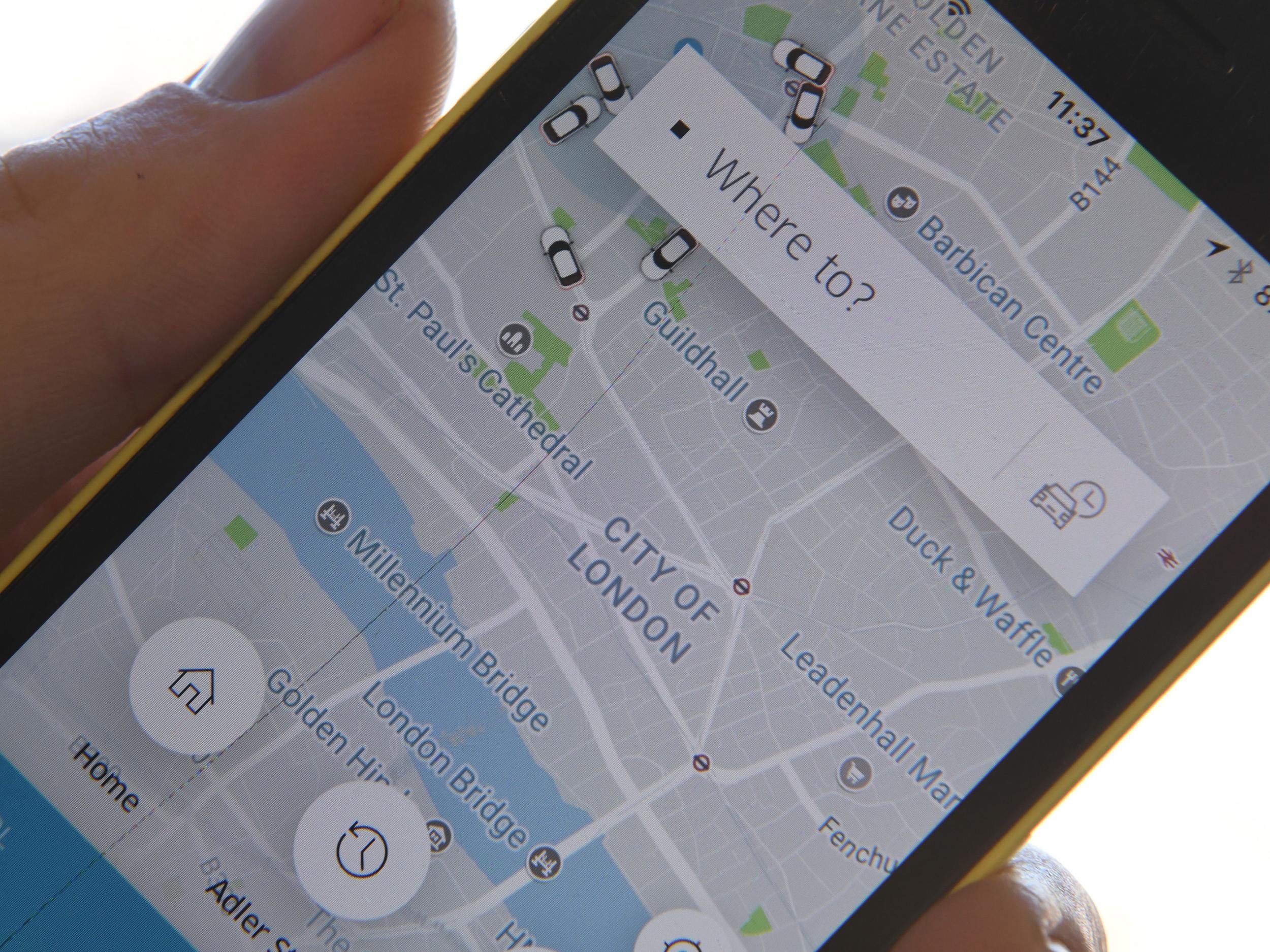

So it is, then, that Uber, the greatest boon in personal transportation since the Model T-Ford, will be smashed by these new enemies of change. The European Court of Justice, never the most modernist of institutions, has loftily decided that Uber is in fact a taxi firm, rather than a technology company, and should be regulated (usually more stringently) as such. Immediately the flexible work that Uber has provided for drivers will disappear; soon the service that has provided.

The revolution is over.

The decision is wrong, and not simply for the effect it will have on peoples’ quality of life – it will also compromise the fees the drivers earn and the access to a normally safe and economical service.

The decision is wrong because the Court posed for itself a binary choice. Is Uber a taxi firm or a technology or software company? How about neither? How about if it is, in fact, something we’ve not seen before – a company that has characteristics of a number of different traditional business models, but represents in itself an entirely new business model, not suited to old regulations?

Like with Google, Facebook and Amazon, the bureaucrats and the lawyers are finding it much more difficult to deal with these new disruptive technologies than consumers, who, to put it at its simplest, just download the app, use it and love it.

Legislators and tax authorities, too, find it difficult to deal with them because they represent a way of adding value to services that has not been done before. As usual technology and private enterprise have sprinted ahead of where the politicians, bureaucrats and lawyers are. The reaction, as ever, is to try to slow down progress.

The truth is that Uber is no more a taxi firm than, say, Toyota, who provide most of the Priuses these drivers seem to favour. No one (you’d hope) would pretend that Toyota should take responsibility for the “tools” or capital equipment by which taxi drivers make a living. Nor should Uber. The Toyota Prius is the hardware, the Uber the software; simple as that.

Second is a broad economic argument in favour of deregulation and allowing enterprise and innovation to take its course. It’s probably true that Uber is making life more difficult for more traditional “mini cab” firms, but then they, in turn, made life more difficult for the older cab trade.

Just as the web made life more challenging for TV, and TV threatened radio, and radio once threatened newspapers. Supposedly. And yet all have, in one form or other, survived through adapting to the new conditions. The point about disruptive technologies is that they are just that. We just need to accept that the long experience of humankind shows us that “disruptive” isn’t always bad for society as a whole.

Unless we – especially in post-Brexit Britain – embrace change, new technologies and new business models, then our economic prospects will be dismal indeed. Global Britain’s capital, London, is not going to be a very impressive place to live and work if its mayor simply bans Uber and tells people to catch the night bus instead.

I am braced for the modern-day Luddites who will attack me for ignoring the personal safety of people, especially women, who have been attacked by Uber drivers, and ignoring Uber’s shortcomings in vetting those who sue its services.

Well, I am not complacent about that; and of course women need to be confident that when they get into a car with an Uber driver they will get home safely. A separate regulatory regime for a new business model such as Uber could accommodate that.

I just think of all those who find themselves in some corner of London or any other place on a dark cold night, maybe the worse for wear, far away from a cab they can hail or a bus or train home, and who just want to get home in one piece and quickly, and, yes, cheaply. Why would we want to regulate that option out of existence?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks