I have groundbreaking NHS tech inside me – but then it failed

My graphs were so pretty – seven days straight with my blood glucose in the target range, writes James Moore. Then I did a blood test and found my blood was as sweet as a pumpkin spiced latte with two shots of syrup

I had it in my sights: a unicorn. A week in which my blood glucose level stays in the target range 100 per cent of the time.

For a type 1 autoimmune diabetic, who is still on old-style, multiple daily injections of the insulin that my body can’t produce, this is extremely difficult. I’ve only done it once before.

But the graphs produced by my iPhone from data provided by the electrode in my arm that monitors my levels were saying a repeat was possible.

They were so pretty. As close to a straight line as a T1 can ever get. I’m a champ, I thought, patting myself on the back. (I confess, I was also thinking of the polite “f**k you” I would be able to give to the less-than-sympathetic clinic I have to go to in today’s malfunctioning NHS).

But those graphs were a lie. The sensor was a dud. In fact, my blood glucose was running hot. It was sweeter than a pumpkin spiced latte with a double shot of syrup.

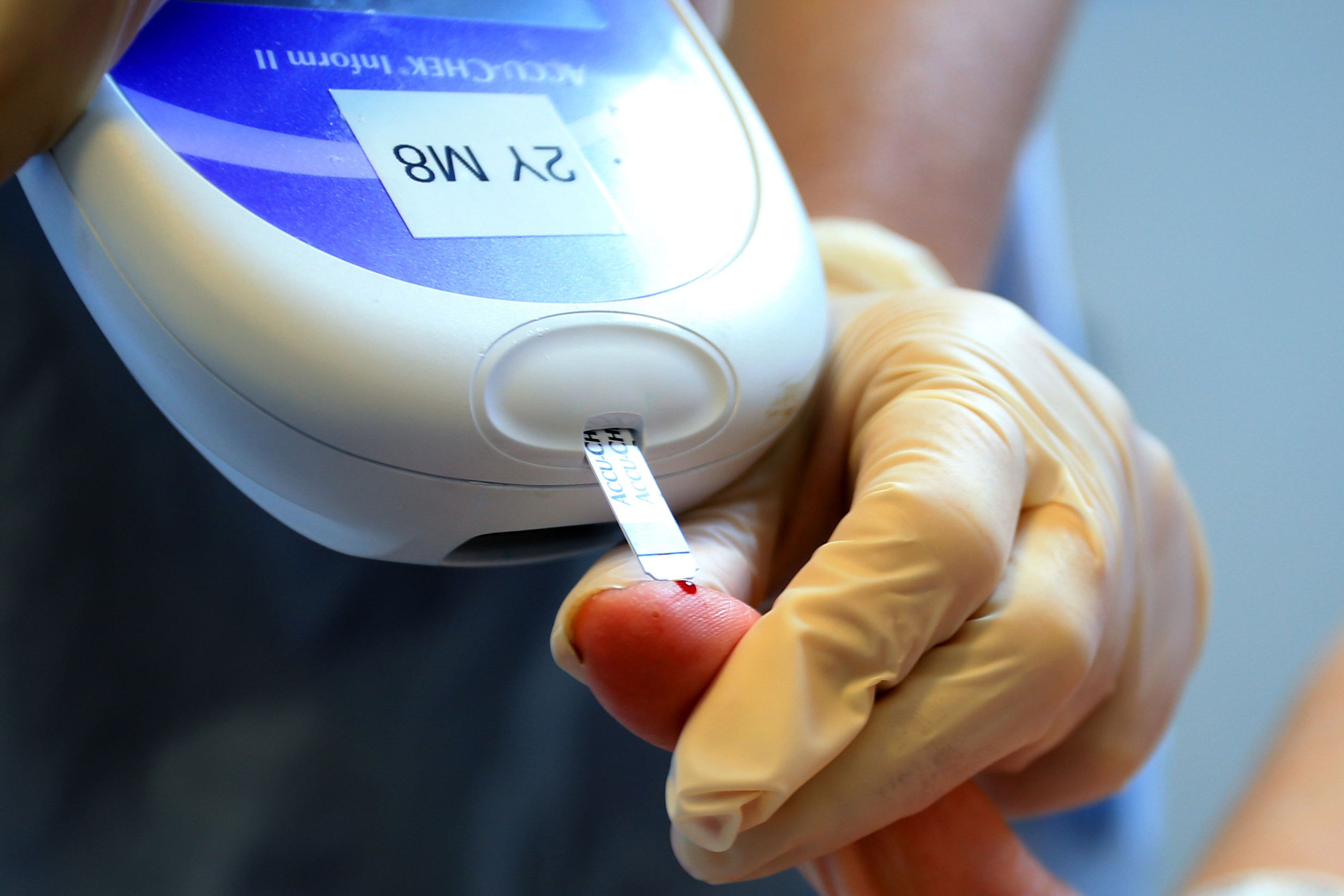

I smelled a rat when the line started trending down and Haribo sweets – my current favourite low blood sugar cure – had no apparent effect. So instead, I went old school and I stabbed my finger for a blood test. The lower of the two readings I took listed my blood sugar at 26.7 mmol/L. Colloquially – that’s sky high. Think Virgin spaceplane high.

By comparison, the British Heart Foundation lists typical blood sugar levels for a non diabetic – whether type 1 or type 2 or one of the rarer forms – at between 4 and to 6 mmol/L before meals, and lower than 8 mmol/L two hours after eating.

I had not recorded a reading that high for at least ten years while under the old regime, in which I had to blood test several times a day to keep track of my levels.

How long had my blood been so thick and syrupy? Just the one day? Or for all four in which the graphs were gorgeous?

Needless to say, I received no warning that this might happen when I was prescribed the kit at said clinic – that was a mistake on their part. The gap between the two readings was so wide it was disturbing. I tore the sensor out. It took me the best part of the evening, and several painful and bloody fingers, to bring things back under control.

So, how common is this type of error? A quick glance at a diabetes chatroom told me it is, actually, very common, with users reporting issues with roughly half their sensors. They are used by some people with type 2, as well as type 1. These claims obviously have to be taken with a pinch of salt – we are talking about the internet, after all.

However, an investigation by the American non-profit Consumer Reports (CR) found that “diabetes devices account for more adverse event reports – including malfunctions, injuries, and deaths – than any other category of medical device submitted to the Food & Drug Administration (FDA).”

The report also outlined that “the FDA told CR that 25 million to 30 million Americans use diabetes devices, and the large numbers of reported incidents reflect ‘this high volume of use’.”

But CR spoke to Madris Kinard, a former FDA analyst, who said that “the large number of people using the devices can’t fully explain why these numbers outdistance any other device by far.”

This is disturbing stuff. In my case, a device failure resulted in an indeterminate but relatively short time with high blood sugars or hyperglycaemia. Over the long term, this can lead to a range of nasty complications.

Type 1 diabetes is a malevolent pixie of a condition. After our immune systems go into overdrive, mostly when we’re young, we are permanently robbed of our ability to produce insulin. Without that, we can’t process carbohydrates. When they build up in the blood it wrecks just about everything – the heart, kidney, liver, eyes, blood vessels, you name it.

Thankfully, mine is usually under good control. I can survive such a malfunction. However, in the case of extreme tech fails, involving insulin pumps rather than sensors, people have died.

Back in 2019, for example, The Independent reported on the case of a T1 who lost their life after their pump delivered four days’ worth of insulin in less than an hour. This is mercifully rare. But it’s enough to chill my (sometimes syrupy) blood.

Tech has delivered a treatment revolution and looks set to radically reduce complications, improving lives and easing pressure on the NHS. And no one wants to go back to the past – when I started out, we used glass syringes with huge needles that looked like they’d been plucked from an adaptation of Shelley’s Frankenstein. My mother periodically boiled them in a pan on the hob to sterilise them. Ugh.

Despite the issues I faced (and the borderline obsession I grew with checking the device), I would not trade my sensors in for stabbing my fingers ten times a day.

We need tech like this to be at the top of its game – people’s lives are (literally) at stake. That is, of course, if they can get hold of it to begin with....

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks