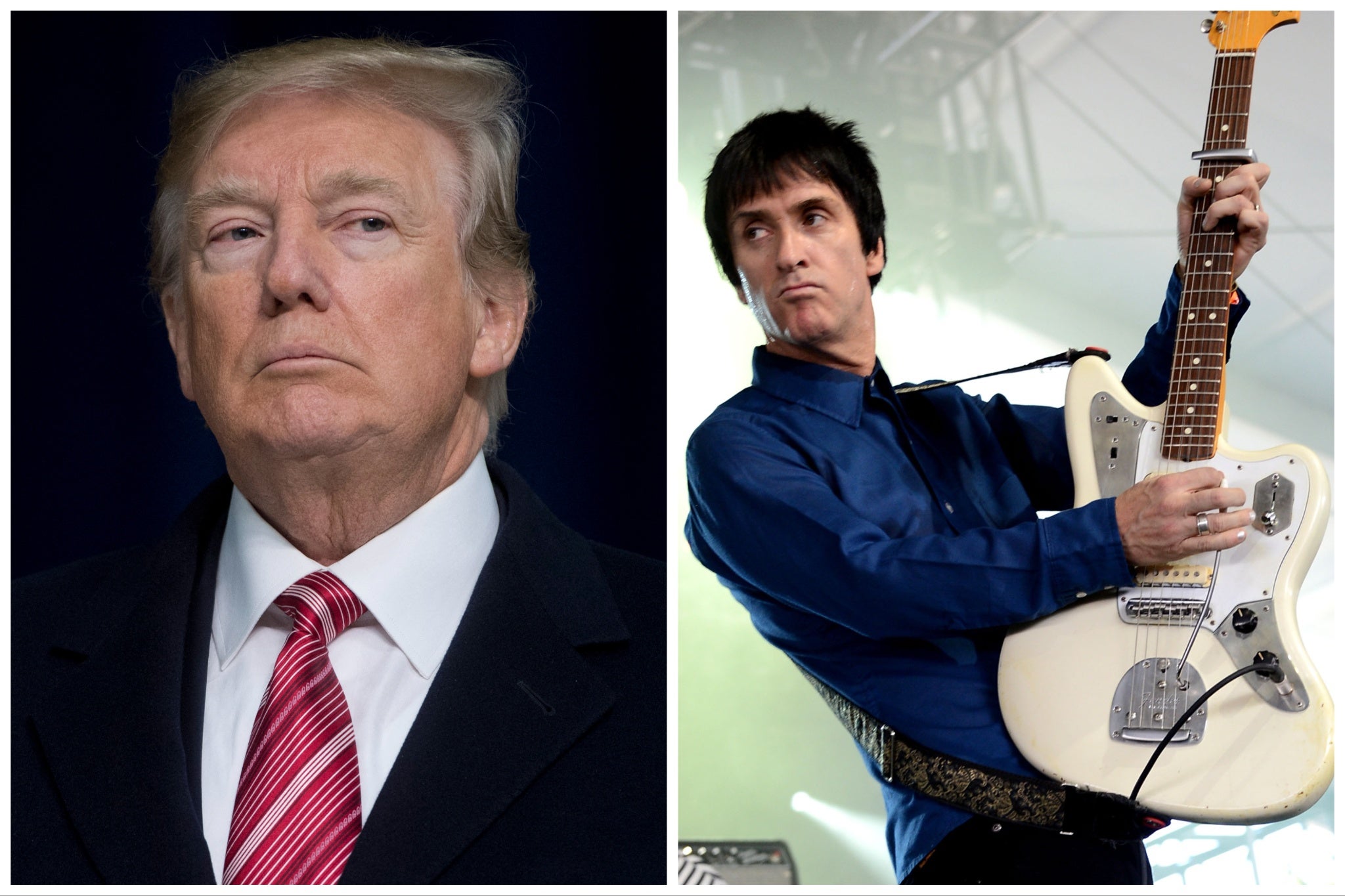

The Smiths’ objection to Trump using their songs does us all a disservice

Guitarist Johnny Marr is in good company, along with artists like Abba and the Rolling Stones, of musical acts who do not want their songs used by the political right. But limiting your art to use by specific groups of people undermines the claim that it is art to begin with, writes David Lister

Johnny Marr, once guitarist and co-songwriter with 1980s band The Smiths, has blown a gasket. He is furious that Donald Trump is using a Smiths song “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want” as his campaign music. Marr does not want his song associated with a man who is politically on the right. And Trump is even further to the right than Marr’s former bandmate Morrissey.

Marr tweeted about Trump’s use of his song: “I never in a million years would’ve thought this could come to pass.”

Johnny Marr is not the first recording artist to object to their music being used by Trump. During his 2016 campaign he came on stage to the sound of the Rolling Stones song “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”. At first, Mick Jagger found this amusing and wondered aloud if this meant he would get an invitation to the inauguration at the White House. But he later stopped finding it funny and Trump was threatened with a cease-and-desist directive.

This had been tried before. Abba, believe it or not, considered a cease-and-desist when the late Republican presidential candidate John McCain used their music. Of course, some of us toyed with the idea of a cease-and-desist when Abba released “Super Trouper”, so there’s a certain irony there.

Poor old McCain managed to offend several pop icons in his choice of campaign music. Chuck Berry wasn’t happy and John Mellencamp actually issued a cease-and-desist order.

And then there are the oddities of politicians using or just liking rock songs for the wrong reasons. Ronald Reagan used Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” in his campaigns, believing it was a patriotic ode to good ole America, whereas it was, in fact, a bitter tale of an unemployed Vietnam War veteran. David Cameron, when prime minister, infuriated Paul Weller of The Jam by saying how he loved the band’s “Eton Rifles” when he was a schoolboy at Eton. Weller made it clear that he did not want Cameron’s fandom. The song was actually a vitriolic satire on social divisions in Britain, though I suspect that even as a teenager Cameron realised that it wasn’t really a marching song for the Eton cadet corps.

Cameron was also an early target for Mr Marr. After he expressed a liking for The Smiths, Marr wrote: “Stop saying you like The Smiths. No you don’t. I forbid it.”

But I believe that rock stars are quite wrong to be irked when their music is used by politicians they disapprove of. It’s not just that it can be interpreted as virtue signalling, it’s something much more important: limiting their music to one side of the political spectrum diminishes it – and them – somewhat.

Great music is art – and art, once it is “out there”, belongs to everybody. Like a play or a novel or a painting, it belongs to everyone to make their own interpretations, to use and to love.

George Orwell did not live to see how opposing sides on the political spectrum used his books Animal Farm and 1984 to support their ideological views. But if he had lived, I can’t believe he would have expressed indignation at this. He would have relished the debate and the irony. Because the books were supreme art, they were open to different interpretations and could be related to by anyone, whatever their political leanings.

I once asked Harold Pinter what he thought about certain interpretations of one of his plays, and he said simply: “The texts are out there.” Once published, they had left his jurisdiction and belonged to audiences, readers, directors and whoever else, to take from them what they wished.

It’s no great leap to see music also occupying this space. A true artist should glory in the fact that their work can be loved – and yes, even used – by wildly different groups of fans. Even fans whose politics they abhor.

Aggressively asserting that your work is one-dimensional is not the best way to back up your claim that it is also art. Best to give a wry smile and say nothing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks