50 years since the day the Troubles broke out, Northern Ireland's citizens are still silenced and ignored

With a failed administration in Belfast, an indifferent British government and disgruntled citizens on the ground, in many ways it is like 1968 all over again

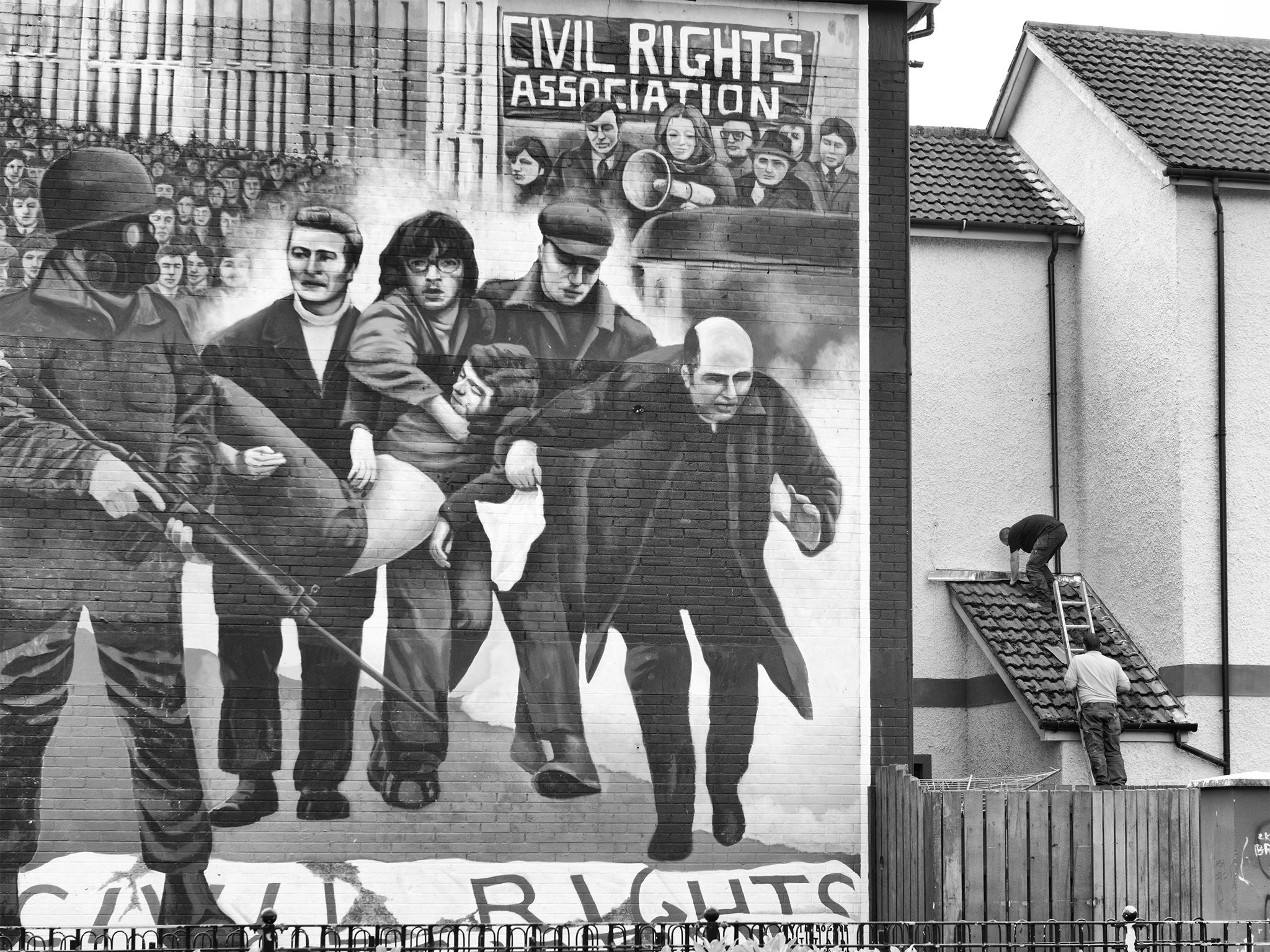

It was 50 years ago today that most people agree the Troubles really began in Northern Ireland, after the brutal suppression of a civil rights march in Derry.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association had been formed the previous year to protest a discriminatory state. While working class Protestants were among those affected, and among those who took part in the movement, it was largely the Catholic population who were denied jobs, housing and even the right to one man, one vote, in what was declared “a Protestant state for a Protestant people”.

The march on 5 October 1968 was banned by the Northern Ireland government and, subsequently, the RUC police force attacked peaceful demonstrators with batons and fists as they walked on their own streets. An RTE cameraman captured the images, and that evening the world got to see the angry culmination of almost half a century of unchallenged discrimination and oppression within the United Kingdom.

What they also saw was the ugly birth of a conflict which would quickly spin out of control, becoming a bloody and brutal battle over whether Northern Ireland should be British or Irish. The next 30 years, as they say, is history.

When I was growing up in the 1990s, Northern Ireland was still fragile, but hope was in sight. My earliest childhood memories read like a chronology of a changing country, seen through curious and confused eyes.

Soldiers checking the car as we crossed the border, walls spray-painted with acronyms I didn’t understand, arriving on my first day of school to find all the windows were smashed and boarded up, my father reading a story about a “ceasefire” one morning on Ceefax; the Good Friday Agreement arriving through the post, and then – out of nowhere – the Omagh bombing, the first thing that ever truly frightened me. As children in the playground, we wondered if it could happen to us next. I was eight years old.

1998 brought the miracle of peace and power sharing, and I never took for granted that I was living in a better world because of it. Resolution and reconciliation were a long way off, but at least there was relative peace.

The people of Northern Ireland have worked hard to live together side by side, in spite of two conflicting constitutional aspirations, continued economic difficulties and what can only be described as an epidemic of post traumatic stress.

No one who lived through the Troubles ever wants to see scenes like Omagh again. Yet sadly, dissident paramilitary groups wait in the dark to seize upon political unrest, economic decline, social change, anger, or even simply boredom.

When I look at the black and white photographs of 5 October 1968, I see a very different Derry to the one I call home today, but the same spirit endures. Then, it was a faded industrial city beset by undeniable poverty, yet men like my grandfather were there in their Sunday best – a picture of pride and dignity.

It is sobering to consider that the men and women who were marching that day were demanding that people in Northern Ireland be heard, treated equally and granted the same rights as citizens across the rest of the UK. In 2018, this is all too familiar.

Northern Ireland is back in a very similar position. Its citizens are being denied rights enjoyed elsewhere in the country, like same-sex marriage, access to abortions and official recognition of the Irish language. Again, this is happening at the hands of Unionists in Belfast – this time in the shape of the DUP.

On Brexit, Northern Ireland went completely ignored during the referendum campaign, even though our geographical position was always bound to end up as the biggest obstacle to the UK’s departure. The hard border which would bring a 300-mile physical target for terrorists looks dangerously close to becoming a reality.

We voted to Remain, and support for staying in the EU has now risen to 69 per cent. We face the brunt of the economic fallout from Brexit, and polls show a united Ireland is a strong possibility if we crash out with no deal. Again, on all of this, London just isn’t listening.

With a failed administration in Belfast, a British government only interested in the short-term appeasement of Unionists, disillusioned and disgruntled citizens on the ground, and an overarching sense that we are sleepwalking towards a new disaster, in many ways it is like 1968 all over again.

No one can predict what will happen next, but we can decide how we respond to it. Northern Ireland must again invoke the spirit of the peaceful protesters who stood up for their rights and marched – not the violent hands which tried in vain to extinguish them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks