This is what it’s like to do Ramadan fasting in the Scottish Highlands, where days are more than 19 hours long

At Eid, we all try to make our way to the mosque in Inverness to meet up with each other – and throughout Ramadan, we’re happy to ask the (many) questions from our non-Muslim Scottish neighbours. They’re certainly not shy about asking us about our faith and our practices

Ramadan days in Scotland are here once again: 30 days of fasting in what are the longest, and warmest, days of summer.

Many will know that Muslims refrain from eating anything during the day in Ramadan, but people are usually surprised to discover that Muslims also do not drink anything. In the Scottish Highlands, the summer days are very long and it never truly becomes dark. This means that the fast lasts for more than 19 hours a day.

Fasting begins at dawn and lasts until sunset. A long time without food and water. Or a lovely cup of tea.

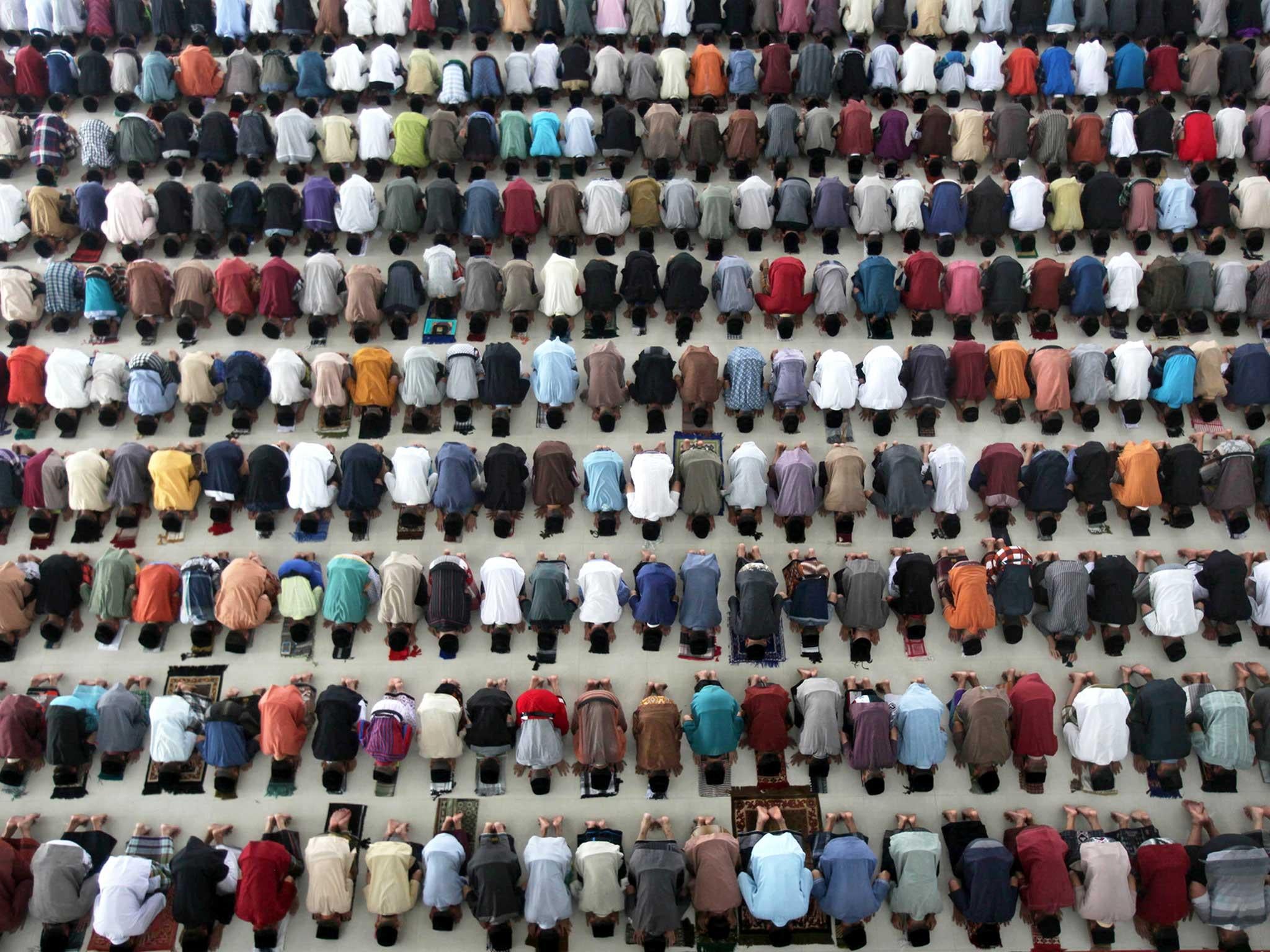

Ramadan is also a time when Muslims try to spend much more time in prayer, increase their reading of the Qur’an, perform as many good deeds as they possibly can and increase their giving to charity. We have to fit all these extra activities into our day while doing all the normal things like going to work, doing chores and looking after our children.

It’s very easy to become dehydrated and to suffer the effects of going without sustenance – headaches and tiredness are par for the course. In many ways, it’s a major ordeal. So what on earth do we Muslims actually do it for?

The main purpose of Ramadan is to bring us closer to God. But Ramadan is also a time of sharing and community. When we break our fast at sunset, we gather together with our families, friends and neighbours, sharing from plates of food with dishes from all around the world. It’s like having a party every night of the week for 30 days. Then, at the very end, we have a huge celebration called Eid.

Obviously, the Muslim population in the Scottish Highlands is fairly small, with only a few hundred Muslims living in or near Inverness. At Eid, we all try to make our way to the mosque in Inverness to meet up with each other – and throughout Ramadan, we’re happy to ask the (many) questions from our non-Muslim Scottish neighbours. They’re certainly not shy about asking us about our faith and our practices, nor should they be. It presents a great opportunity to set straight some inaccuracies or prejudices that have reached them through the mainstream media throughout the year.

When Ramadan is over, it feels like something is missing in our lives. It feels like saying goodbye to an old friend. We descend upon the mosque in our best clothes, hug and greet each other, and then head off to get-togethers with our families and friends. Gifts and stories are exchanged.

Then it will be time to say goodbye to Ramadan for another year and, despite the long Scottish days and the hunger and the thirst, we end up looking forward to it coming round again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments