Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As one of the 19,000 free and independent electors of Norwich South whose vote helped to elect the newly fledged Labour MP Clive Lewis to Westminster last month, I have naturally been following his parliamentary career with interest. What has Lewis been up to since he put the sitting Liberal Democrat, Simon Wright, to the sword on 7 May? He began promisingly by declaring that New Labour was dead and making a maiden speech in which, abandoning the tradition that such debut appearances are non-contentious, he attacked plans to turn one of the local comprehensive schools into an academy. But what about that other vital litmus test of the up-and-coming young Labour member? Who, in other words, does he intend to support in the leadership election?

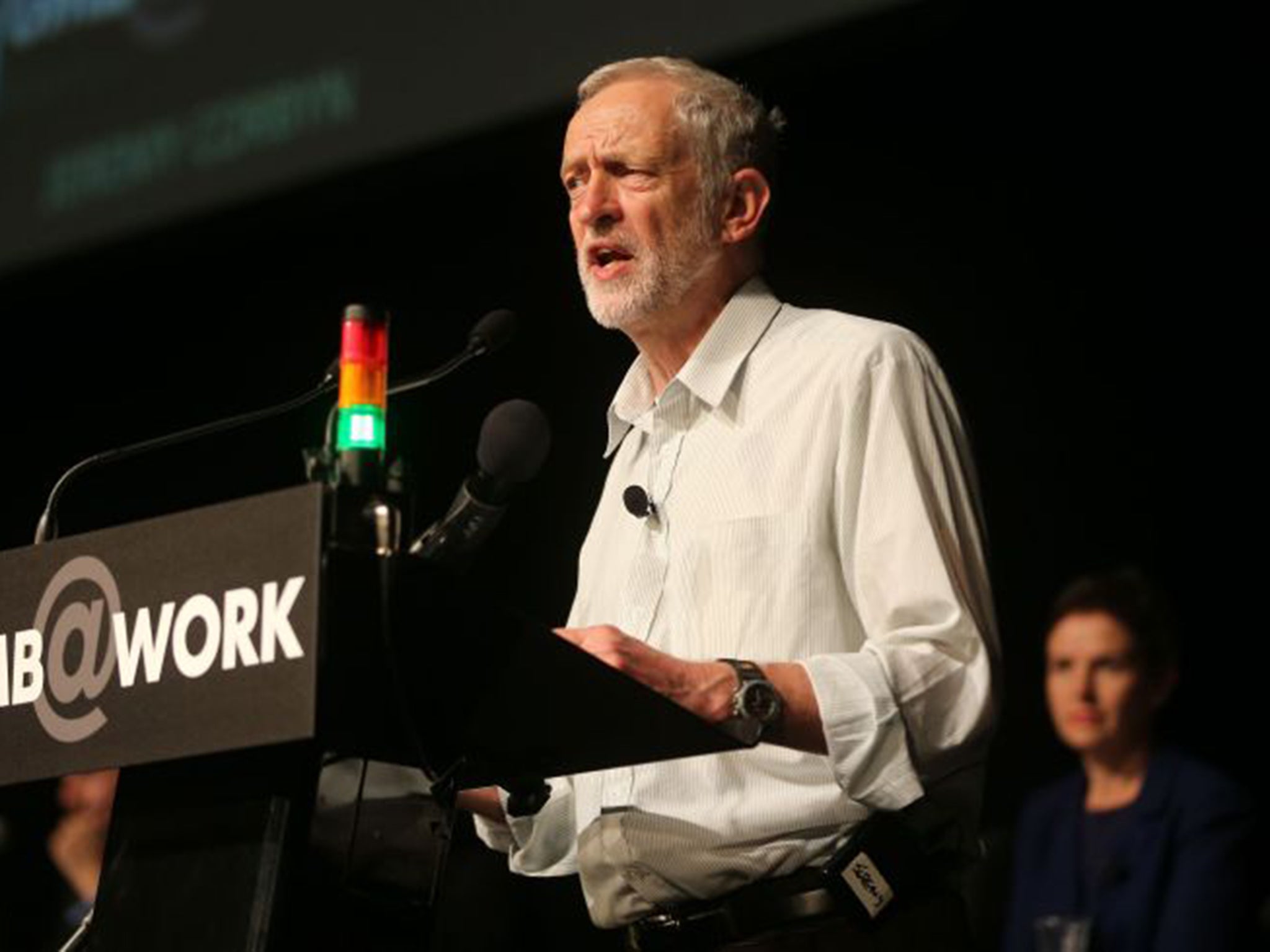

And here, sad to relate, the reports are less encouraging. For Lewis, according to our local paper, the Eastern Daily Press, and in the company of perhaps a dozen other hard-line lefties, is apparently keen to vote for that gnarled old veteran of the Campaign Group, Jeremy Corbyn. At which point, Labour Party member that I am, I wondered whether the cross marked in Lewis’s favour five weeks ago hadn’t been a mistake. No disrespect to Corbyn, who has conducted a long campaign on behalf of the Guantanamo detainee Shaker Aamer and whose support for those excluded from this consumer materialist society of ours has been unflagging, but in party-political terms he is a throwback to an age that was passing into extinction at around the time he was first elected to parliament in 1983.

And so a vote for Corbyn, even should he acquire the 35 parliamentary backers sufficient to put his name on the ballot come September, is pretty much a vote wasted, a gesture that will do nothing except to confirm his supporters’ status as a member of Labour’s awkward squad, on whose antics the new leader’s eye will uneasily turn over the course of the next four and a half years. So why does Lewis feel that he has to join this exclusive and backward-looking club? Naturally, a man has to be true to his beliefs (and having heard Lewis at the hustings, I should say that they consist of a determination to let none of the battlegrounds of the 1980s stay unvisited). Principled opposition to something you believe to be wrong is always a good thing, inside politics and beyond it, and however limited the number of supporters you begin with. Where would the anti-apartheid campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s, or the movements to decriminalise homosexuality and abortion, have been had their members not resolved to carry on regardless of short-term criticism? “Progress” in our recent history is nearly always a matter of a few honourable people digging in until such time as majority opinion comes round to their way of thinking.

On the other hand, Lewis has the misfortune to belong to a party for whom the futile gesture has always been an integral part of the way in which it goes about its business. Take, for example, the leadership election of 1980, when it was clear to anyone who was not a paid-up member of the Tribune Group that the only senior Labour politician capable of defeating Margaret Thatcher was Denis Healey. Alas, sentimentalism won the day and Michael Foot duly went out to be slaughtered at the general election of 1983. At this point it was again clear to anyone beyond a circle of trade union barons and constituency activists that the only senior Labour politician with a chance of succeeding where Foot had failed was Roy Hattersley. Whereupon, this great movement of ours voted for Neil Kinnock, who duly went out to be slaughtered at the general elections of 1987 and 1992, leaving the average Labour voter to reflect that ideological purity is a wonderful thing while seldom doing very much for the mass of ordinary people whose interests it is intended to promote.

The futile gesture is not, of course, confined to politics. Military strategists would be lost without it. 1864, the wonderful Danish television drama about the Schleswig-Holstein question, which ground to a close on BBC4 the other weekend, was a kind of object lesson in pointless endeavour, in which a cabal of nationalist politicians seemed almost to pride themselves on the grim resolve that prevented them from suing for peace and sending thousands of their soldiers out to certain death. And who can forget the Beyond the Fringe sketch from the early 1960s, in which the hapless recruit Perkins is told by his superiors that the time has come for a futile gesture and the sacrificial victim is himself.

The arts, too, are full of writers and painters zealously flying in the face of trends that they know will sweep them into obscurity, like some dodo proudly disporting itself on the Mauritian strand while the musket-toting Dutch settlers close in for the kill and their dogs ransack the surviving nests for eggs. One of the British literary groupings for whom I always feel a profound sympathy is the “Georgian” poets and essayists of the later 1920s and early 1930s. Woolf, Joyce and “The Waste Land” had come and blown them away; the smart money was on vers libre and rapt interior monologues in the style of Molly Bloom; but they went on writing their tinkling little poems about country weekends and moonlight falling on apples, and trying to convince themselves that T S Eliot would eventually be exposed as a charlatan.

To read a Georgian poem, written in the era of the Jarrow March and three million unemployed, whose subject matter is more likely to be the pleasures of a country walk in Sussex, is to raise the question of the futile gesture’s underlying psychology. For there comes a point where principle, or rather the chance of that principle being put into practice, becomes less important than what might be termed the satisfactions of maintaining it, when one decides to continue with a struggle not because there is any chance of victory but because it bolsters and glorifies what Anthony Powell would have called the struggler’s personal myth. Did the last Stuart pretender, the self-styled Henry IX, still maintaining a notional claim to the throne long years after the defeat of the 1745 rebellion, think he would ever return? Probably not, but, even at this late stage, the mythological structures erected around the tantalising visions of kings over the water were too seductive to be thrown away.

All of which brings us back to Jeremy Corbyn and Clive Lewis. By chance, on the day of Lewis’s maiden speech I received an email from the local Labour Party inviting me to a constituency meeting at which MP and councillors would deliver their monthly reports. According to the agenda, this gathering would conclude with a mass rendition of “The Red Flag”. And here it seemed to me was another gesture in its way as futile as a vote for Corbyn. Why on earth, in 2015, should anyone bent on improving the lot of the underprivileged feel the need to sing an anthem that is practically synonymous with the suppression and exploitation of hundreds of millions of people?

The equivalent on the right would be for the Conservative Party conference to conclude with the delegates singing C F Alexander’s immortal hymn “All Things Bright and Beautiful” and being careful to include a verse which is usually left out in these sensitive times: “The rich man in his castle/The poor man at his gate/God made them high and lowly/And ordered their estate.” For the futile gesture is essentially rooted in the past, the product of an approach in which bygone glories are reckoned more alluring than the distractions of an irritating present – and, in a curious way, failure is more satisfactory than success. Whatever their commitment to serving the underprivileged, stemming the tide of inequality or anything else, it is hard to believe that anyone happy to warble “The Red Flag” at meetings really expects Labour to win another general election.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments