The untold story of the deaths at Hajj

Iranian diplomat Ghadanfar Rokonabadi disappeared after being caught up in the mass panic on last year’s Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He was smart, occasionally humorous and detailed in his replies to my questions. Officially, he was an attaché at Iran’s high-walled, black-painted embassy in Beirut, but back in 1996 I thought Ghadanfar Rokon Abadi was an Iranian intelligence officer. He wore his neat black beard well-trimmed and if his eyes looked older than his 40 years, his English was heavily accented but impeccable, his manners polite almost to the point of exaggeration.

He joked with me of the day an Israeli helicopter suddenly appeared beyond the embassy compound at the height of Israel’s so-called Operation Grapes of Wrath invasion of southern Lebanon. “We all waited for it to attack us," he said. "It didn’t come. Then we thought it would attack our homes near the compound. Of course we were afraid!”

Rokon Abadi knew a lot about weapons. And he always expressed his preparedness for "martyrdom". He was a tough man and, over the years, I concluded that he never told me a lie. He was frank about Iran’s financial and military support for the Lebanese Hizballah, and even appeared before students at a Christian university in east Beirut to defend his country. True, he maintained there that the Egyptian revolution should be supported while Syria’s should not – Syria’s revolution was founded neither on poverty or oppression, he contended with awe-inspiring lack of subtlety – but he fought his corner and insisted that Iran’s theocracy was also representative because its parliament was elected.

In 2010, Iran had sent him back to Beirut to become its ambassador; a year later, when the revolution against Iran’s Syrian ally Bashar al-Assad broke, he found himself in one of those blind corners that every diplomat must loathe. It was one thing to support Hizballah resistance to Israel; quite another to explain Hisballah’s support for Syria in its battle against the Syrian resistance around Damascus. When Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visited Lebanon and toured the south of the country to gaze over the border at Israel – or occupied Palestine, as the Iranians called it – and promise to “liberate” Jerusalem, Rokon Abadi was there, smiling beside his president. But he was a lucky man, at least for the time being.

When Sunni Islamists, reportedly with Saudi support, staged a suicide attack against his embassy in November 2013, killing 23 embassy employees, Hizballah guards and civilians, Rokon Abadi was just leaving the consular buildings for a trip into Beirut. The blast almost broke down the great iron gates of the embassy and swept past Rokon Abadi, leaving him untouched but his top security man dead.

I last saw him in the embassy when we embarked on a heated discussion of Iran’s death penalty during which, I fear, he found me extremely hostile. Iran had decreed that a young Iranian Azeri woman convicted of adultery should hang in Tabriz, and I protested against her death sentence. What right did Iran have to decide which of God’s creatures should live or die, I asked, not least after a grossly unfair trial? Rokon Abadi was taken aback and tried to explain, calmly but with growing unease, that the Iranian judiciary was independent and that he and other government officials had no power over its decisions. The woman was pardoned, but Rokon Abadi did not pardon me.

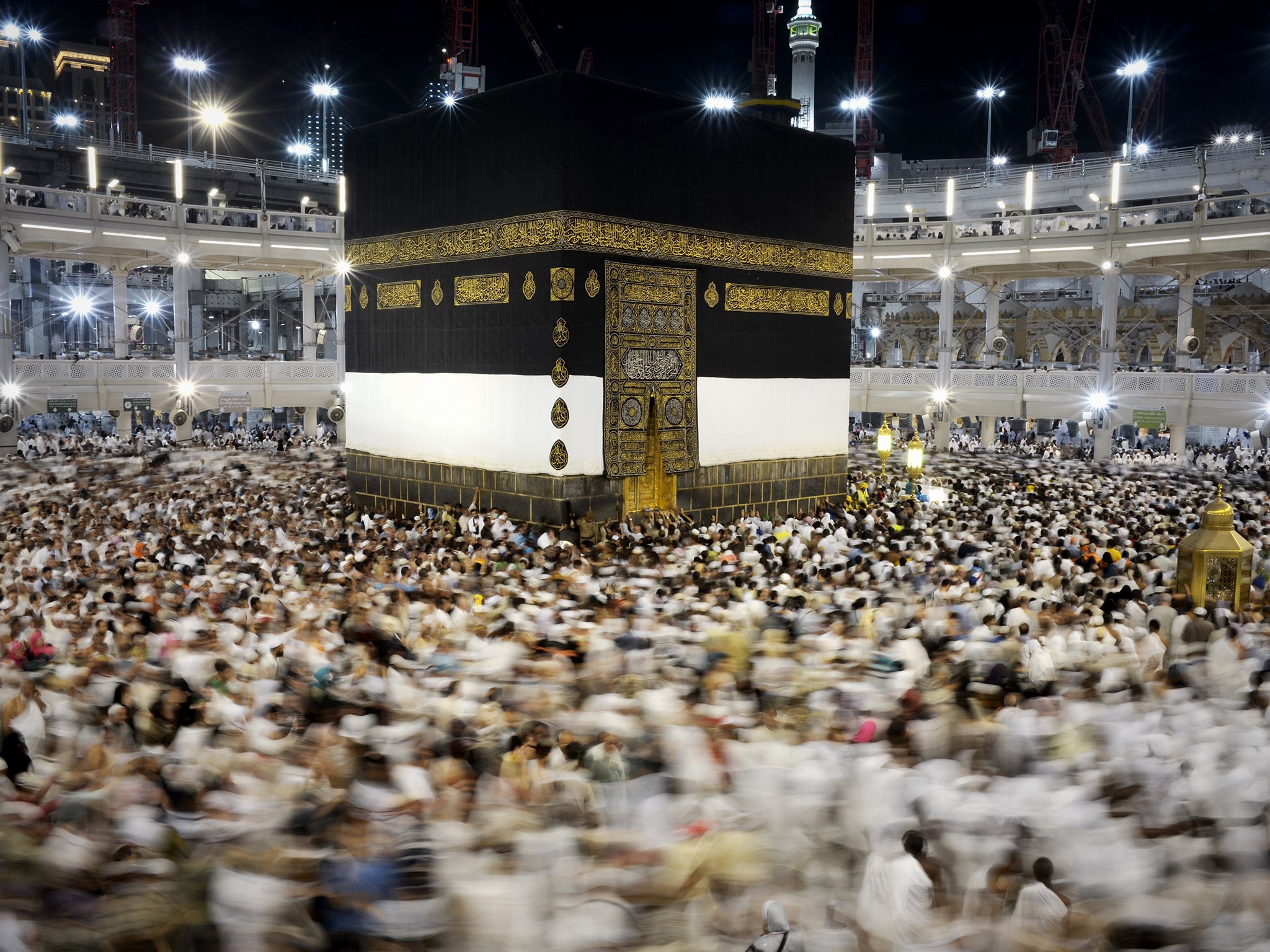

Although one of his officials accompanied me back to my car, talking all the while of the Koran’s wisdom on guilt and punishment, the very last time I saw the ambassador – at a Pakistan national day reception which he fled the moment it turned into a Pakistani ladies’ fashion show – he could scarcely bring himself to shake hands with me. He returned to Tehran in 2014 as one of its top diplomats and, I felt sure, among its wisest intelligence men. Then, fatally, he went on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca last year and, on 24 September, was caught up in the mass panic at Mina and mysteriously disappeared.

Iran stated that it held the Saudi monarch – officially the “keeper” of the Holy Place of Mecca – personally responsible for the deaths of more than 2,300 people, 464 of them Iranians who had been “deliberately mistreated”, among them senior officials of the Islamic Republic. Only days later did it emerge that the most senior of all those officials to die was Ghadanfar Rokon Abadi. No wonder the Iranians were enraged.

Could this really have been just a terrifying accident, a tragedy of immense proportions for so many pilgrims which had, just by chance, cost the life of Rokon Abadi? Over the past two months, two Iranian-Saudi negotiations have been held to arrange this year’s Hajj. They failed to reach agreement because, according to Tehran, there were no specific security plans to protect Iranian pilgrims; and the Sunni Saudis would not allow the Iranians to stage their traditional Shiite demonstration “bera’at al-moshrekin”, "distancing themselves from idolatry". It was always left to other pilgrims to decide whether the "idol-worshippers" were the Saudi monarchy or the United States and Israel.

There had been previous bans on the Iranians. In 1987, anti-US and anti-Israeli demonstrations by pilgrims had been crushed by Saudi forces who killed 402 civilians, 275 of them Iranians. This, of course, was at the height of the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war in which Iraq’s invading forces were militarily supported by vast Saudi financial subventions and US military assistance. The Iraqi government is today under Iran’s security umbrella but the Saudis could scarcely turn Arab pilgrims away from Mecca; so Iraqis would make the Hajj, Iranians would not.

The dispute fits all too neatly into the incendiary conflict between Tehran and Riyadh that now pours blood onto the battlefields of Syria, Iraq and Yemen, the Sunnis largely suffering for the Saudis, the Shiites for Iran. Among the Shiite victims, it is now clear, was Ghadanfar Rokon Abadi, the courtly diplomat who knew much about weapons and who spoke to me about death and martyrdom and who met his fate in Islam’s holiest city.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments