The Prime Minister cannot just dismiss the Church of England's attack on his government with a soundbite

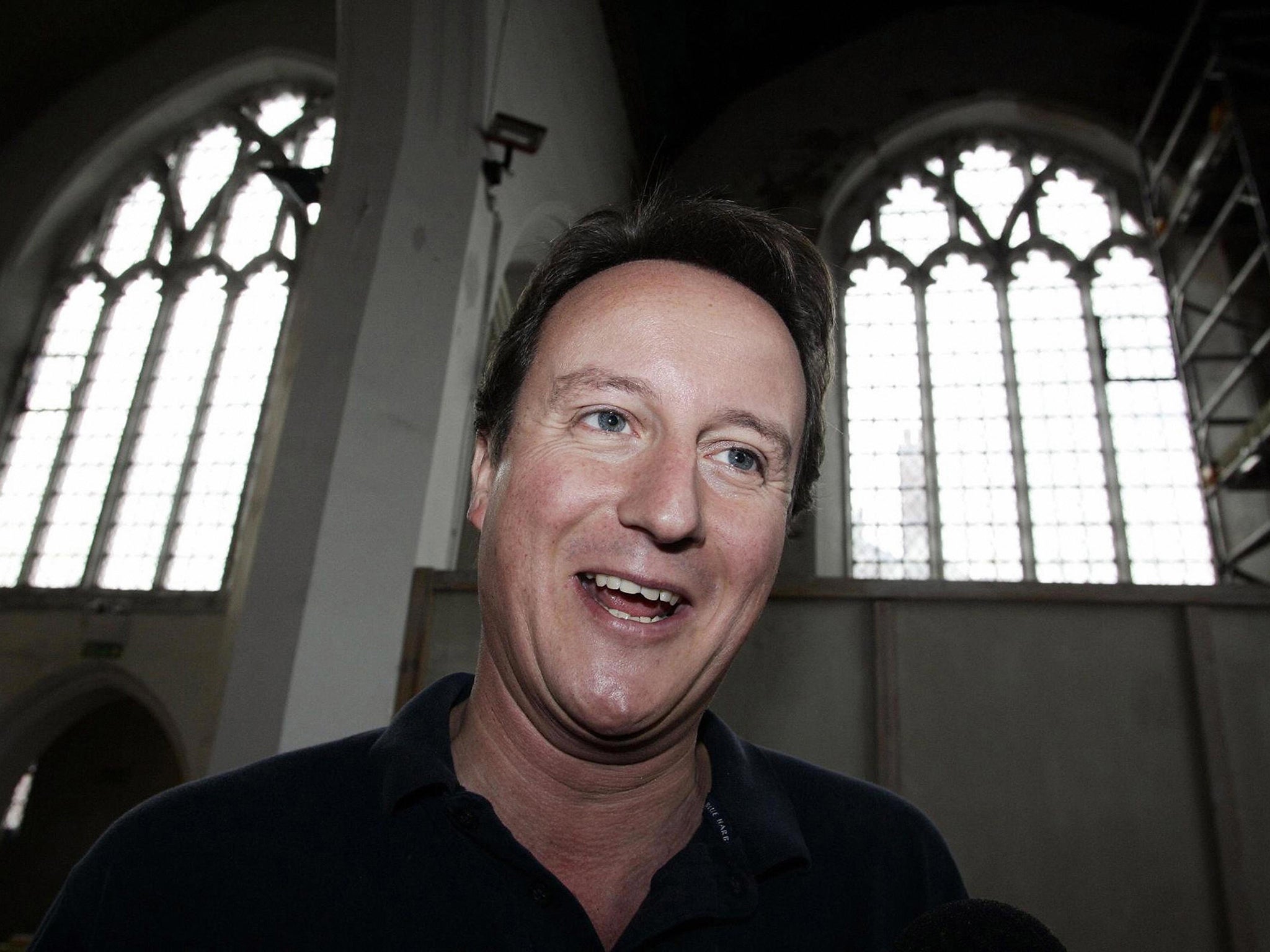

David Cameron may not welcome the damning Anglican report on the state of the nation, but it is written from the blighted parishes of the frontline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At least David Cameron didn’t label last week’s damning Church of England report on the state of the nation as “Marxist”. That was the angry response of Margaret Thatcher’s government in 1985, when Robert Runcie published his excoriating Faith in the City analysis on the impact of her policies. She never forgave the slight and, when Runcie retired, punished the church by pushing through the appointment of the hapless George Carey, its least effective Archbishop of Canterbury in living memory.

By contrast, David Cameron’s response last week to a book of essays by the Archbishops of York and Canterbury, which made headlines by accusing his government of “casting aside” entire cities, was polite but slightly wounded. Speaking in Washington before meeting President Barack Obama, he said that he “profoundly disagreed” with the prelates’ conclusions that his economic policies were based on a “lie”, but looked forward to a debate with John Sentamu and Justin Welby (presumably in preference to one with Nigel Farage and Ed Miliband).

Given the damning analysis offered by the churchmen in On Rock or Sand?, Cameron’s was a curious reaction. Colleagues in government were much more robust, producing reams of statistics on growth, employment and regional development to counter the picture the book paints of the UK economy being, in Archbishop Welby’s words, “a tale of two cities”, with politicians too obsessed by Middle England, “entire cities” beyond London and the South-east “cast aside” in a “lose-lose” scenario, and a widening gap between rich and poor that has resulted in a nation “ill at ease with itself”.

It’s tempting to fit the Prime Minister’s limp reply into the pattern of a gradual firming-up of his own religious conviction during his time in 10 Downing Street. He comes from a church-going background – his mother, Mary, is a sidesman in her local Anglican parish – but back in 2008, as Leader of the Opposition, he joked that his faith was “a bit like the reception for Magic FM in the Chilterns – it sort of comes and goes”. By Easter 2014, though, he was busy publicly talking up Christianity’s contribution to Britain and describing his own domestic efforts to teach his children about God.

Cynics suggest that his words were a sop to church-going Tories who had been alienated by his support for gay marriage, or preparing the ground for shoehorning his children into a high-achieving Anglican school since, as Prime Minister, his alma mater was out of the question for their education. His new-found evangelical fervour may even have been prompted, it has been said, by his potential leadership challenger, vicar’s daughter Theresa May, playing up her own church-every-Sunday Anglicanism.

But this is lazy analysis. Thatcher may have dismissed Faith in the City as an act of treachery but two years later, on the morning after her 1987 election victory, she was pledging, “we must do something about those inner cities”. She had shot the messenger, but she’d heard the message.

There were, of course, plenty of other reasons back then to realise that her policies were creating urban wastelands. And, today, for all the Government’s boasts about its custodianship of the economy, it is never short of learned reports telling it that talk of prosperity in many inner cities and across great swathes of North England, Scotland and Wales is about as real as Nick Clegg’s chance of ever being prime minister.

The difference when the criticism comes from the two most senior figures in the Church of England, though, is that they are uniquely well placed to know what is actually going on in some of Britain’s most blighted areas. When night comes to the sink estates of our towns and cities, the committed professional classes who work there every day, trying to make a bad situation less bad, pack their bags and go home to cosier locations. “There are some areas of our inner cities,” says the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, in a recent interview with Third Sector magazine, “where the only person from the outside still living there is the priest.”

It is that witness, that first-hand knowledge gained by going the extra mile, that trust that has been built up as a result with those on the margins, which gives this Anglican report from the frontline both authority and a peculiar capacity to wound. As Lord Scarman remarked at the time of Faith in the City, having earlier authored his own report on riots in inner city Brixton, it was “the finest face-to-face analysis we have yet seen”.

Face-to-face reporting – that’s what the Church of England is offering. It is there for people in need in a way that others just aren’t. It was put to Williams, in the same interview, that you don’t need religion to roll up your sleeves to improve the lot of the poor. “That is a speculative hypothesis,” he replied. “The bare fact is that most of the food banks in this country are run by the churches.”

There has been much talk in the past 10 days of the need to respect religious beliefs. It is often presented as something absolute, regardless of the reality of those beliefs. And, indeed, you can quite legitimately ask why should anyone respect an organisation like the Church of England, when it drags its feet on granting women equality at the altar and punishes gay people for being the way God made them. Yet, in its work in the inner cities, its hands-on, 24-hours-a-day commitment to those on the margins, the Church of England gives us something to respect.

Which is why the Prime Minister knows he cannot just dismiss its attack on his government with a soundbite and statistics.

Peter Stanford is a former editor of the 'Catholic Herald'. His biography of Judas will be published this Easter by Hodder & Stoughton

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments