My rape documentary was banned in India - but #HerVoice protests during Modi's visit can stop it disappearing

It is against the law in India to name a rape survivor even if she or her family wish to publish her name. This is because shame and dishonour adhere to her and her family after sexual violence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 16 December 2012, a young physiotherapy student, Jyoti Singh, was gang raped on a moving bus in Delhi, India. After the six perpetrators had sexually attacked her, they pulled out her intestines and threw her body, naked and bleeding, out onto the road. Tragically, there was nothing new or even unusual about this crime: such horrific acts are carried out relentlessly and regularly in India, and indeed across the world.

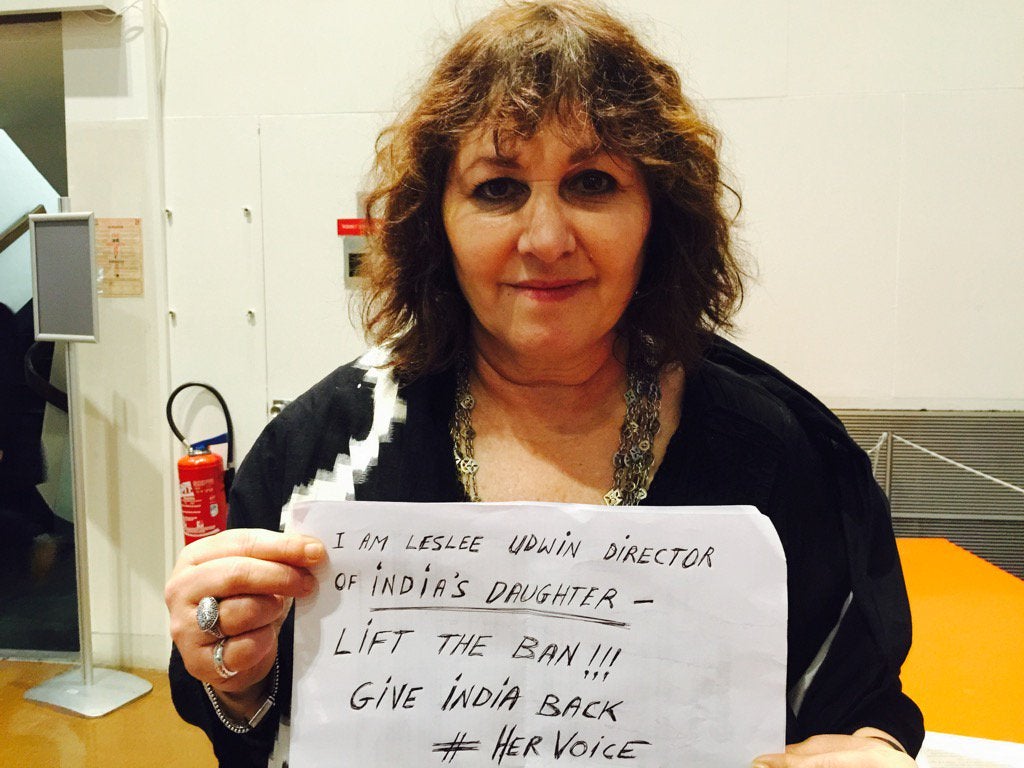

But what was new was the response to it in India. For the first time, there was a mass mobilisation of civil society demanding justice for women and girls, and doing so with the most admirable passion, commitment, and tenacity. Witnessing and admiring this from my home in Copenhagen, I was compelled to join these protests and amplify these exceptional voices by making a documentary about the case. The resultant film, India’s Daughter, has sparked more conversations about gender inequality since its release earlier this year than have been heard in the last decade.

Imagine my shock, given my motivation in making the documentary, when five days prior to its scheduled release on Indian TV, the Indian government banned it without even having seen it. Hysterical Indian MPs in the Houses of Parliament cried that I had orchestrated a campaign to shame India. The supreme irony, of course, is that it is the ban itself that brings shame on India, not the film. Countries across the world have joined the conversation willingly, ready to acknowledge their guilt and commit to doing something about it. Only India pretends, by “virtue” of this misguided ban, that they do not have such a problem.

This attitude of reflex denial is reflected in societal attitudes in India. It is against the law to name a rape survivor even if she or her family wish to publish her name. This is because a further gross injustice is perpetrated against the survivor: shame and dishonour adhere to her and her family after a rape. Shame and dishonour are (or should be) all with the perpetrator. But the real shame and dishonour belongs to the society that has taught the perpetrator that women are of lesser or no value compared to men. It is the same programming that leads the police to ignore rape complaints, and leads women to not even report them.

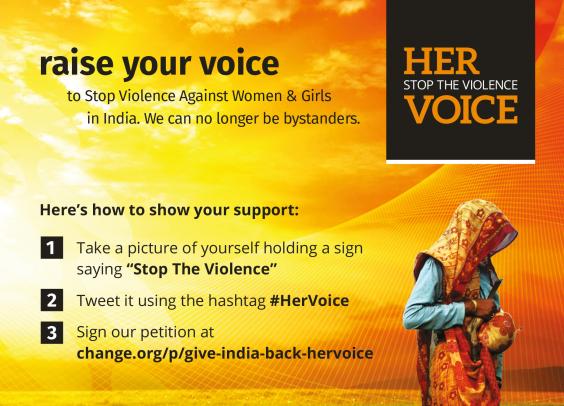

It is for this reason that I stand side by side with the nine Indian Non-Governmental Organisations that make up the #HerVoice campaign. With a petition and a social media platform, they aim to raise awareness of the urgency of the issue of sexual violence and put international pressure on the government to actively tackle rape culture and better enforce existing rape laws. Changing the mindset of Indian society is the only answer to preventing sexual violence. We need to stop being reactive to the fallout of gender inequality, and start rooting out the cause.

Dr Ambedkar, who drafted the Indian constitution, said: “We will measure the progress of Indian society by the progress of Indian women.” These words have never been more relevant or more urgent than they are now. Only by acknowledging that the problem of rape exists in India, as well as in the rest of the world, can progress be made of the sort Dr Ambedkar called for.

A protest against the ban on India’s Daughter and on behalf of #HerVoice is to be held from 11.30am at Wembley Stadium on Friday 13th Nov. Prime Minister Modi is due to address an Olympic style rally there that day during his state visit to Britain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments