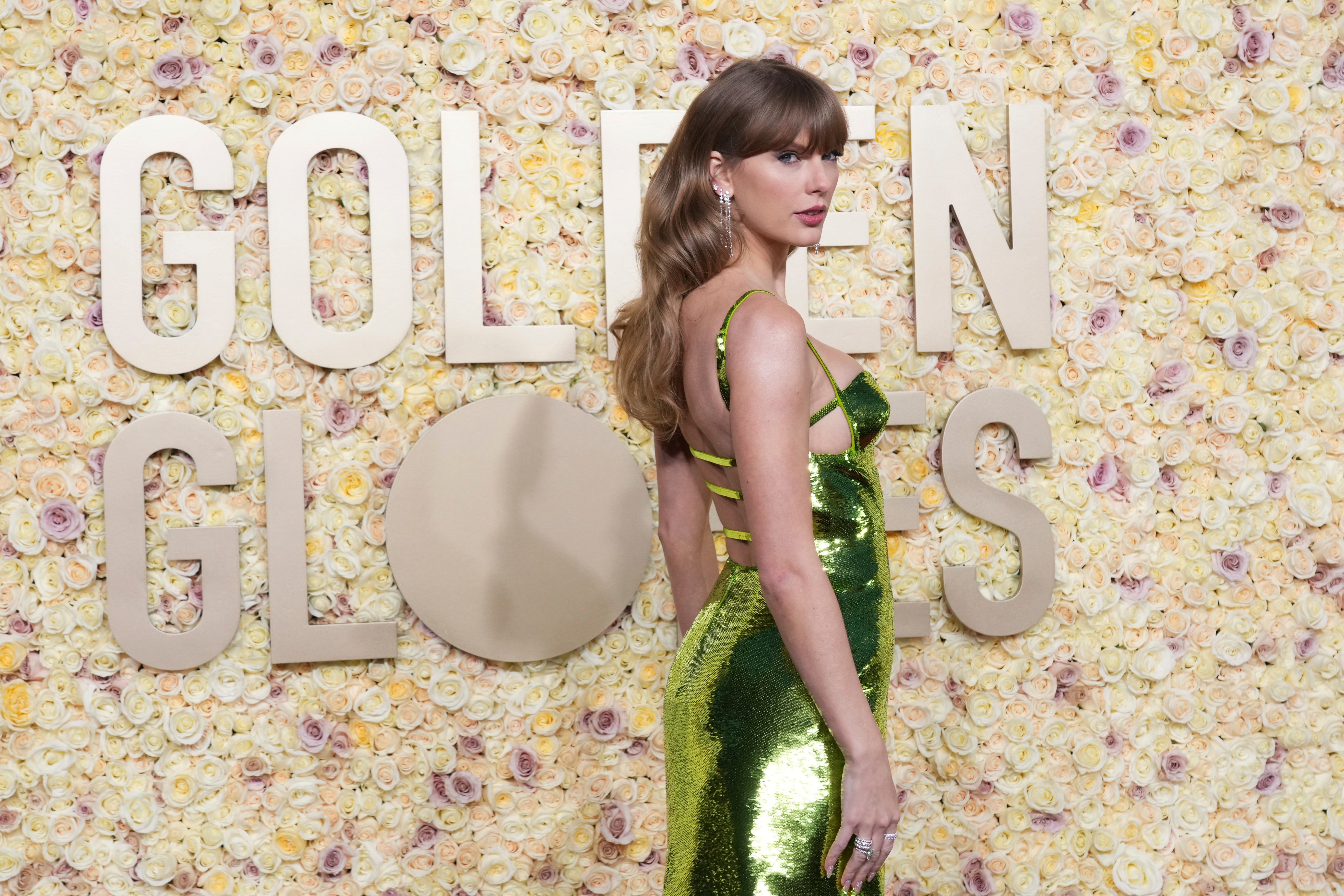

The Taylor Swift deepfakes show why we urgently need AI regulation

We must take stronger measures to prevent the circulation of this material, which enables the abuse of women and girls, writes Labour MP Sarah Owen. After all, if the world’s most famous singer isn’t safe from AI, then how vulnerable are the rest of us?

Hopefully, you haven’t seen the images. But you wouldn’t have to look very hard to find them. Many users of X (Twitter), Reddit and other mainstream social media channels have inadvertently stumbled across them. Twitter claims to be rooting them out, but they are fighting a losing battle with their own technology. Taylor Swift’s friends and family are apparently “furious”, and rightly so. She is reportedly considering legal action.

This raises two questions, both for Taylor and any other victims of deepfake abuse: how on earth were these pictures allowed to be made and shared in the first place, and what legal recourse do victims have?

The truth is that current legislation does little to stop the production of deepfakes or to protect victims. There are no specific bans on the production of many deepfakes, and rules attempting to stop them being shared are extremely difficult to enforce.

At the moment, only users creating this material, or sharing particular explicit images, are at risk of prosecution – and this is only if those users can ever be found. Worse still, deepfakes are being used at scale for not only sexual abuse but to commit widespread fraud and to impersonate officials and undermine elections.

How can we stop this? Simply going after individuals – who are frequently anonymous – who share deepfakes is bailing out the ocean with a bucket. We can and must stop deepfake production at the source rather than only catching it when it breaks into the mainstream of social media, and when the harm is already done. Stopping deepfakes means holding developers of these AI systems to account, and getting tough on the companies that host and enable their production and distribution.

Currently, deepfake abuse is increasing exponentially. Unprecedented progress in AI has made deepfake creation fast, cheap and easy. The vast majority of deepfakes (at least 96 per cent) are sexual abuse material. Virtually all the rest are for fraud (deepfake fraud increased by 3,000 per cent in 2023).

From 2022 to 2023, deepfake sexual content increased by over 400 per cent. Sites hosting deepfake sexual abuse material have become incredibly popular: the most popular site was visited by 111 million users in October 2023. Deepfake sexual abuse disproportionately affects women, with women representing 99 per cent of victims.

Teachers are battling deepfakes in the classroom: there have been horrifying stories of students creating deepfakes of their classmates and their teachers, often via easily accessible “de-clothing” apps. Some students are even blackmailing others using deepfakes.

Deepfakes also pose serious challenges to my profession. Female MPs are already the target of sexual abuse, online and offline, and deepfakes give perpetrators another weapon in their arsenal. This will likely further discourage female candidates from running for office – yet another unwanted gendered obstacle.

Deepfakes threaten democracy by enabling disinformation on an unprecedented scale. In 2023, a deepfake audio clip purported to be a recording of Sir Keir Starmer abusing staffers was circulated. Within a couple of days, the audio clip gathered nearly 1.5 million hits. Just a month later, deepfake audio of Sadiq Khan apparently saying Remembrance Day should be postponed was widely shared on social media.

With half the world’s population facing elections this year, the widespread creation and proliferation of deepfakes presents a growing threat to democratic processes around the world.

The public strongly supports a ban on deepfakes. A series of recent polls, across many countries, found massive support for a ban on deepfakes among citizens, and across the political spectrum. In the UK, 86 per cent support a deepfake ban, and just five per cent oppose it.

What can we do in the face of such powerful technology being used at such a large scale? The government should make the creation and dissemination of deepfakes a crime, and empower victims harmed by deepfakes to sue for damages. This would not apply to innocuous images or voice manipulation such as satire, memes, or parody. However, it would apply to non-consensual sexual content, deliberate misinformation and fraud.

The solution will require banning deepfakes at all stages of the supply chain. Regulation should apply to the companies producing deepfake technology, the people creating individual deepfakes and all stages in between.

Firstly, this begins with liability for the AI companies and rogue developers that produce the underlying technology for deepfake production. Secondly, developers of AI products must show that they have taken reasonable measures to prevent deepfakes.

Lastly, we need to get tough on the companies that host and enable deepfakes. The mass creation of deepfakes is made possible by cloud providers, websites distributing these deepfake models, and a myriad of businesses that enable these practices in the open. This can and must be stopped by holding all of them liable for the harm they cause.

The account that uploaded the deepfakes of Taylor Swift has now been deleted. In all likelihood, the culprit will go free. When the world’s most famous singer finds herself with little recourse against her abusers, it only highlights how vulnerable we all are to this new technology.

Sarah Owen is the Labour MP for Luton North

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks