The Syrian regime once again finds itself locked in the crosshairs of justice

This case is a reminder that the world should think twice before making amends with Assad and welcoming him into the family of nations, writes Borzou Daragahi

A little-noticed legal case filed last week in The Hague is making waves in the world of international justice. The filing could have an impact on victims of torture worldwide, and advance the aim of ending impunity for the world’s most notorious state criminals – regime leaders who abuse and murder their own citizens.

Canada and the Netherlands launched cases against the regime in Syria on 12 June, accusing it of violating the United Nations convention against torture. This historic move is the first time a state has summoned another before the International Court of Justice for torture.

Legal experts have described the case as a first at the ICJ. The institution, sometimes called the World Court, was founded in 1945 as a forum for nations to adjudicate international disputes without resorting to war. Unlike the International Criminal Court, to which Syria is not a signatory, Damascus was an original member of the ICJ.

“This is the first time that a state has brought a case against another state for breaches of the UN convention on torture,” says Toby Cadman, an international law specialist at Guernica 37, a law firm that assisted the Netherlands in preparing the case. “What we’ve already seen has been cases brought before the ICC and cases brought to national courts under universal jurisdiction. This is different. This is about Syrian state responsibility for torture.”

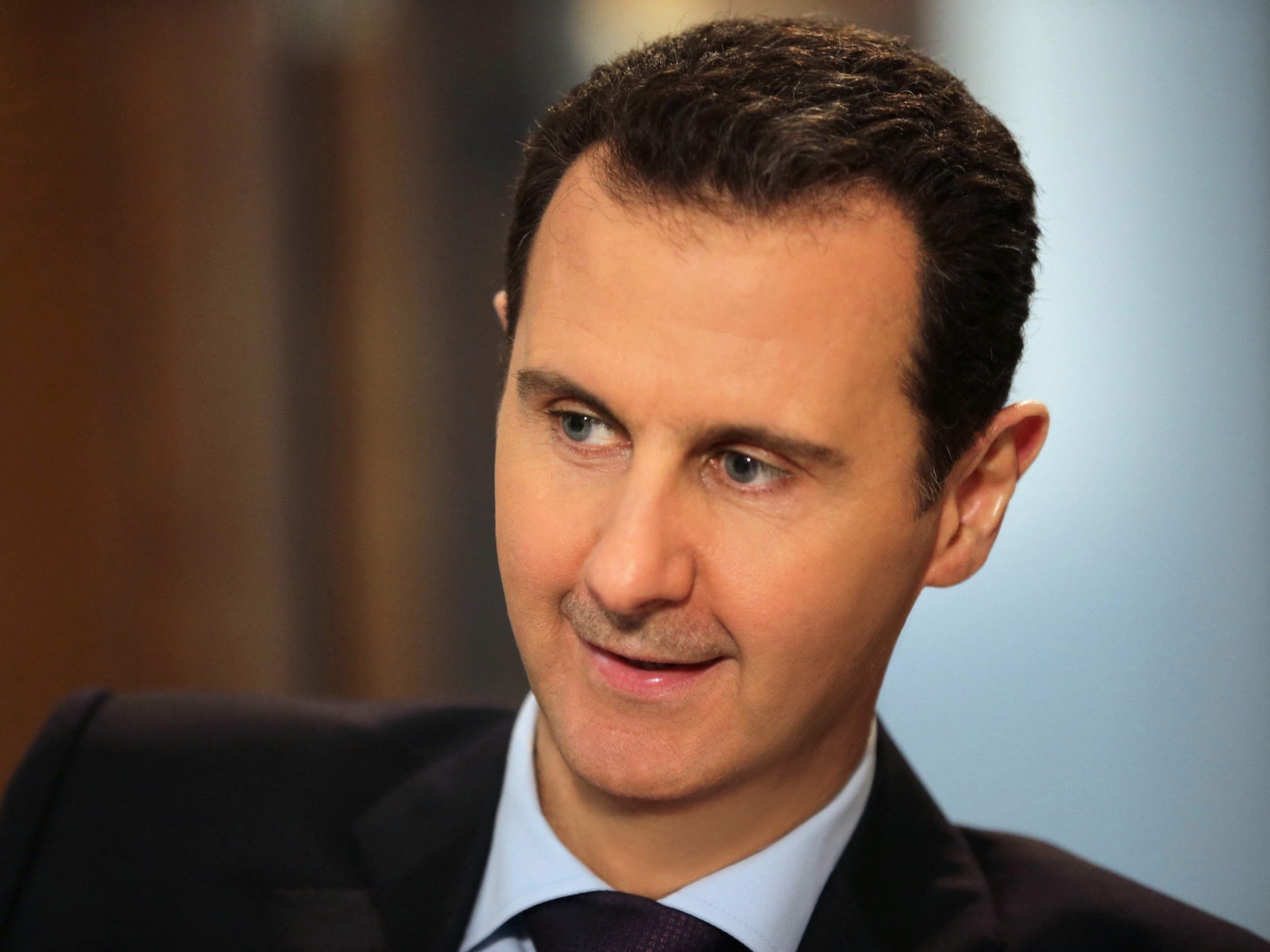

Syria, a country steeped in bloodshed and ruled by the iron fist of Bashar al-Assad, finds itself in the crosshairs of justice once again. With the backing of Russia and Iran, this tyrant has managed to emerge victorious from a gruesome 12-year war, escaping accountability for his crimes. However, the recent court case at the World Court, along with other ongoing prosecutions, serves as a resounding reminder that his actions will not be ignored.

Cadman says that the facts in the case against Syria are rooted in several UN fact-finding missions, commissions of inquiry and investigations about missing and tortured Syrian detainees. Preparations started in 2020. Under ICJ rules, Canada and the Netherlands first had to try to address their dispute through arbitration before bringing it to The Hague.

In the application submitted last week, Canada and the Netherlands accuse Syria of “countless violations of international law” that began with its ruthless repression of civilian protesters in 2011 and continued through a protracted armed struggle.

“These violations include the use of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment … including through abhorrent treatment of detainees, inhumane conditions in places of detention, enforced disappearances, the use of sexual and gender-based violence, and violence against children,” said the filing, which cites the regime’s use of chemical weapons against civilians.

All it takes is one past torture victim to make a case. But this case is not merely about the sins of the past. It is a rallying cry for the thousands of detainees who still languish in Assad’s dungeons, enduring unspeakable horrors day after day. The 11-page filing against the regime describes “ongoing and consistent patterns of conduct demonstrate the systematic use of torture” especially targeting victims groups based on ethnicity, cultural background, religion, gender and sexual orientation.

“The allegations are related to torture being committed on a truly massive scale,” Cadman says. “But there are allegations that there are several thousand if not tens of thousands still at risk.”

Past efforts to pursue Syrian regime figures for their crimes have occasionally been challenged by questions of jurisdiction. But there should be few questions as to whether the ICJ has the authority to try the case, though it may struggle to get what has effectively become a mafia-run narco-state to respond to the allegations. “The case will go forward,” says Cadman. “Whether Syria will engage in the process, we don’t know. But the ICJ will continue regardless and make a determination.”

Possible remedies could include findings for reparations for victims or their loved ones and, perhaps more importantly, an order for the release of present-day detainees.

This case and a number of others focused on the Syrian regime and its abuses are reminders that the world should think twice before making amends with Assad and welcoming him into the family of nations. The ICJ case lays bare the agonising reality endured by those trapped within his prisons. It is a grim reminder that reconciliation means turning a blind eye to his ongoing atrocities.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks