Exclusive polling reveals the public don’t care if you’re a classy worker – or working class

New data has shown that, despite the emphasis on politicians’ roots, most voters don’t actually care about the class background of Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer. Andrew Grice explains what that could mean for the parties’ election strategies

It has become a standing joke at Westminster. Keir Starmer bangs on about being “the son of a toolmaker”, while Rishi Sunak constantly reminds us that his father was a GP and his mother ran a pharmacy. The rolling of eyes in the Westminster village won’t stop them from repeating their favourite lines many times before the election.

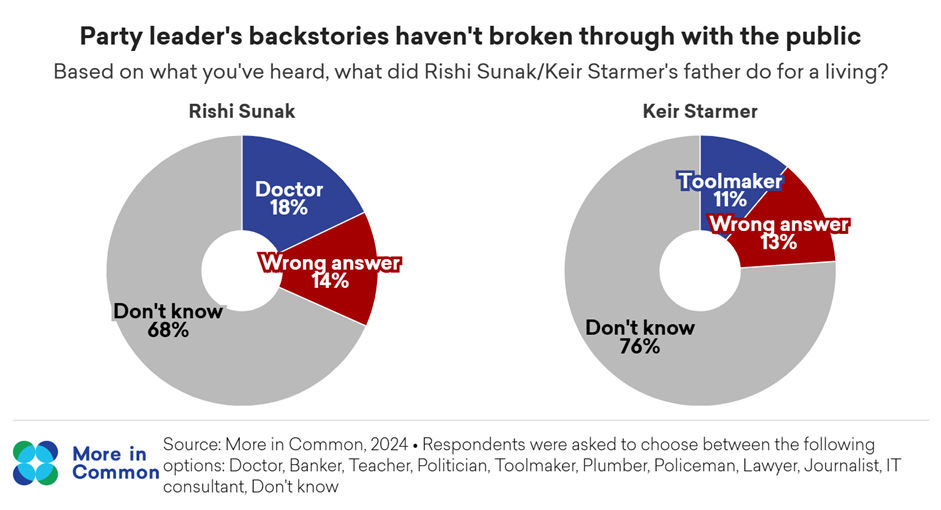

Yet a revealing opinion poll shared with me by More in Common shows that their declarations have sailed over the heads of voters. Only 11 per cent of people know Starmer’s father was a toolmaker, while 18 per cent know Sunak’s father was a family doctor.

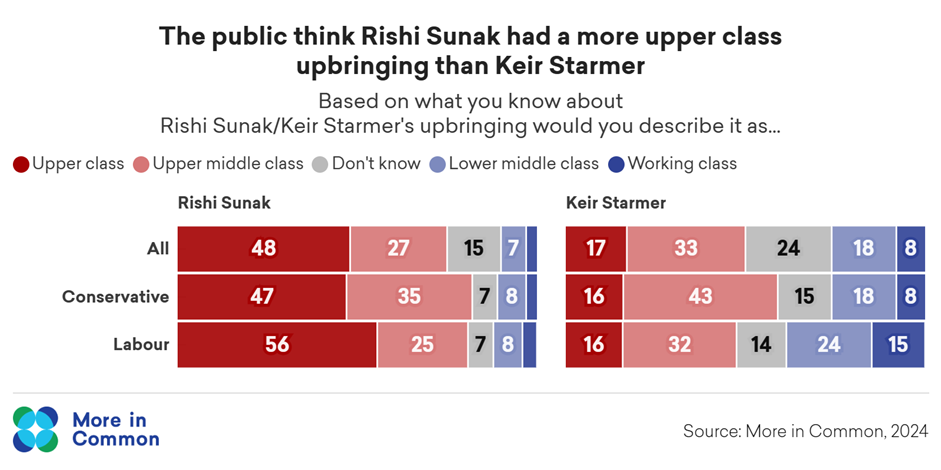

Similarly, Starmer’s repeated references to his “working class” roots have not cut much ice with the public. The biography of him by Tom Baldwin proves beyond doubt that Starmer’s assertion is correct. But only 8 per cent of people (and only 15 per cent of Labour supporters) think the Labour leader had a working-class upbringing. Nor are voters impressed by Sunak’s pitch that he comes from the hard-working, aspirational middle class: he is seen as upper class, while Starmer is viewed as “upper middle class”. The good news for Starmer is that fewer than one in 10 people believe he inherited his knighthood; almost half correctly say that he earned it through public service.

Luke Tryl, More in Common’s UK director, said: “Everyone in Westminster might be sick of hearing that Keir Starmer is the son of a toolmaker and that Rishi Sunak’s dad was a doctor and the family ran a local pharmacy – but the vast majority of the public still has no idea about the backgrounds of the two party leaders. The public’s general cynicism towards politicians is more likely to make them think that both Sunak and Starmer come from more privileged backgrounds. This should serve as an important reminder that most people in the country don’t follow the ins and outs of what goes on in Westminster. We may well hear a lot more about pharmacies and toolmakers in the campaign ahead.”

Indeed, the backstories of the country’s two best-known politicians will feature as their parties play the man as well as the ball. The Tories love nothing more than branding Starmer a “north London lefty lawyer” who defended terrorists such as the now-banned Hizb ut-Tahrir group. Starmer’s riposte is that, as director of public prosecutions, he prosecuted “terrorists, murderers and all sorts of other offenders”.

Senior Tories tell me they are keener than ever to get personal after the local elections highlighted the need to win back voters who have defected to Reform UK. The Tories will also target Angela Rayner, Starmer’s deputy; although she is popular with the wider public, Tory officials believe right-wing Tories and Reform supporters don’t like her. (Interestingly, the Tories don’t spend much time attacking Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor – presumably because Tory voters like her.)

Labour threatens to retaliate by accusing “rich Rishi” of “betting on the misery of working people” as a hedge-fund manager during the 2008 financial crisis. Labour will draw attention to loopholes in Jeremy Hunt’s crackdown on non-dom status to remind voters that Akshata Murty, Sunak’s wife, was previously a non-dom. The biggest danger for Sunak is not that voters view him as rich, but that they perceive him as being out of touch and remote from their daily struggles.

Things can only get nastier. But will most voters be aware of such attacks? Some ammunition will be fired not in public statements but below the radar, in targeted socia-media advertising. Sometimes, ads are designed to provoke a row in order to magnify the message via free news coverage. But playing dirty can backfire, as Labour discovered after an attack ad accused Sunak of not wanting sexual abusers of children to go to jail. The backlash extended to some Labour MPs.

More in Common’s sobering findings suggest that politicians should worry about the gulf between their finely tuned messages and the voters who are not listening.

Will people tune in when the election finally comes? Perhaps, but the biggest obstacle is public cynicism about politicians, and pessimism that things can’t get better. Labour figures worry privately that, although it’s the Tories who have broken their promises, this feeling damages the opposition as well as the governing party.

That Starmer is not admired by voters in the way that Tony Blair was at this stage before the 1997 election probably reflects this disaffection. When asked who would make a better prime minister, Starmer is ahead of Sunak, but “neither” beats both of them. Perhaps Mr Neither should start a political party.

The Tories have convinced themselves that Starmer is Labour’s weakest link. But however clever their attacks might be on his backstory and his policies, I think they will be swamped by a much more powerful “time for change” tide, which will sweep the Tories away.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks