Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Those inclined to think of economics as little more than a disingenuous cover for letting the wealthy and powerful do whatever they like in the name of “market forces” ought to look up the work of Arthur Cecil Pigou.

In the 1920s Pigou, a Cambridge economist, made a significant and lasting impact on the discipline, with his economic theory of the taxation of “negative externalities”. If the action of an individual or a business in the free market causes harm to an innocent third party, that’s considered a negative externality. And Pigou argued that a tax on that externality-generating activity is economically justified in order to compel the individual or business to internalise the cost. The rising financial cost of the activity will then discourage that behaviour – possibly even eradicate it altogether. Thus the welfare of the wide community will be enhanced.

A straightforward example of a negative externality is pollution. Business and households exchange and consume goods and services in a free market. But a by-product of some of their activities can be environmental despoliation. Think of a factory that manufactures televisions, which it sells to customers, but which also pumps out acrid smoke in the production process. Under Pigou’s framework, the state ought to tax that polluting activity to compel the factory to internalise the social cost of the pollution, rather than simply let it foul the air that everyone else has no choice but to breathe. This could push up the price of TVs, meaning consumers bear the cost. Or the tax could hit the firms’ profits because people buy fewer televisions, meaning its shareholders take the hit. Whatever the “incidence” of the tax, the firm would have a financial incentive to reduce its pollution.

Another example is the impact of diet on healthcare. When people eat unhealthily or smoke they often tend to require expensive medical care in later life. In a system of socialised health provision such as the National Health Service, this means the cost of such behaviour falls on the wider community. The Pigovian solution is to tax the cigarettes and unhealthy foods.

The concept can be extended further. When banks expand their operations recklessly they increase the risk of their failure, or of blowing up a damaging credit bubble. A Pigovian solution is to tax the size of their balance sheets, to discourage reckless expansion.

The vast majority of serious economists are generally perfectly comfortable with the principle of Pigovian taxes. They may disagree about the size of the social cost of the negative externality in question and therefore the size of the tax that ought to be imposed. But the principle itself is not a controversial one.

But it’s a very different story for lobbyists – or the “libertarian” pressure groups that often masquerade as economic think tanks. There is much debate about whether George Osborne will put up fuel tax in this week’s budget. The fiscal need is screamingly obvious. The public finances are looking precarious thanks to disappointing tax revenues and weak inflation.

The politics also, on the face of it, look appealing. The oil price has fallen, pushing the average price of a litre of unleaded petrol down to 102p, its lowest level since 2009. A couple of pence on fuel duty would still leave the petrol price well below the levels of a year earlier, leaving drivers’ wallets only mildly lighter.

Yet such is the power of the motoring lobby that even with the oil price collapse and the strains on the public purse it’s touch-and-go whether Osborne will have the courage to do it or not, especially in the run-up to the Brexit referendum. Backbench Conservative MPs have reportedly been lobbying hard against any increase in the fuel duty.

They have history on their side. Since Osborne took office as Chancellor in 2010 he has postponed or cancelled scheduled planned increases in fuel duty no less than 15 times.

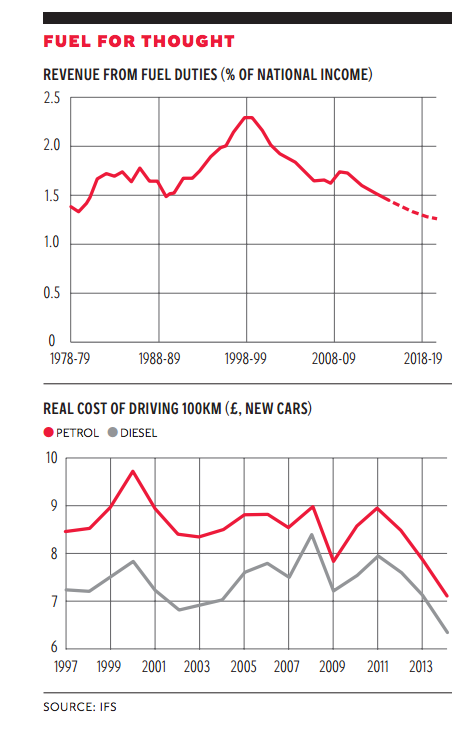

The lobby’s rhetoric is shrill. It talks about a “war on motorists”. But the reality is somewhat less oppressive. Fuel duty is a relatively significant contributor to the public coffers. It is scheduled to bring in around £27bn to the Treasury this financial year. Yet relative to the size of national income, the tax take from fuel duty has been falling steadily for some time. The Institute for Fiscal Studies calculates that as a share of GDP fuel duties have been declining since 2000. At the turn of the millennium they constituted around 2.2 per cent of national income. Today they are down to just 1.5 per cent of GDP. The IFS also estimates that the real cost of driving 100 kilometres in a new car is lower than it has been in 20 years, largely thanks to the development of more fuel-efficient vehicles. If this is “war”, it is one motorists have been winning.

The Pigovian justification for fuel taxes is not elusive. Driving creates carbon emissions. Carbon emissions exacerbate the greenhouse effect. And the economic costs of a warming planet are likely to be extremely large, as Nicholas Stern made clear in his landmark review for the Labour government a decade ago and as every credible economic study of the subject subsequently has confirmed. Climate change is the ultimate economic externality.

It will infuriate the fuel lobby to hear it, but the only serious debate among credible economists is how to tax the externality. The IFS advocates scrapping fuel duty altogether and implementing a road tax whereby drivers would be charged in relation to how many miles they covered. This would incentivise drivers to drive less and also tackle the other externality of traffic congestion at the same time (which the IFS thinks is actually a more significant driving externality than climate change). Another suggestion is a blanket carbon tax, which would not only discourage the consumption of petrol but all other activities that generate carbon dioxide emissions, from plane travel to factory production.

We don’t know what the Chancellor will do on Wednesday. But we surely know what Pigou would do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments