How propaganda from the Russian Revolution brought about today’s ‘troll factories’

Under the ‘iPad president’ Medvedev, the internet brought a new dimension to Russian propaganda. The Kremlin not only controlled the national television, press and an array of loyal digital outlets – it now had a troll army

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week another Russian “troll” was accused of influencing public opinion in the UK, by posting a misleading picture of a Muslim woman “ignoring Westminster terror victims”. This comes after claims that similar bots attempted to sway public opinion over Brexit and the US election.

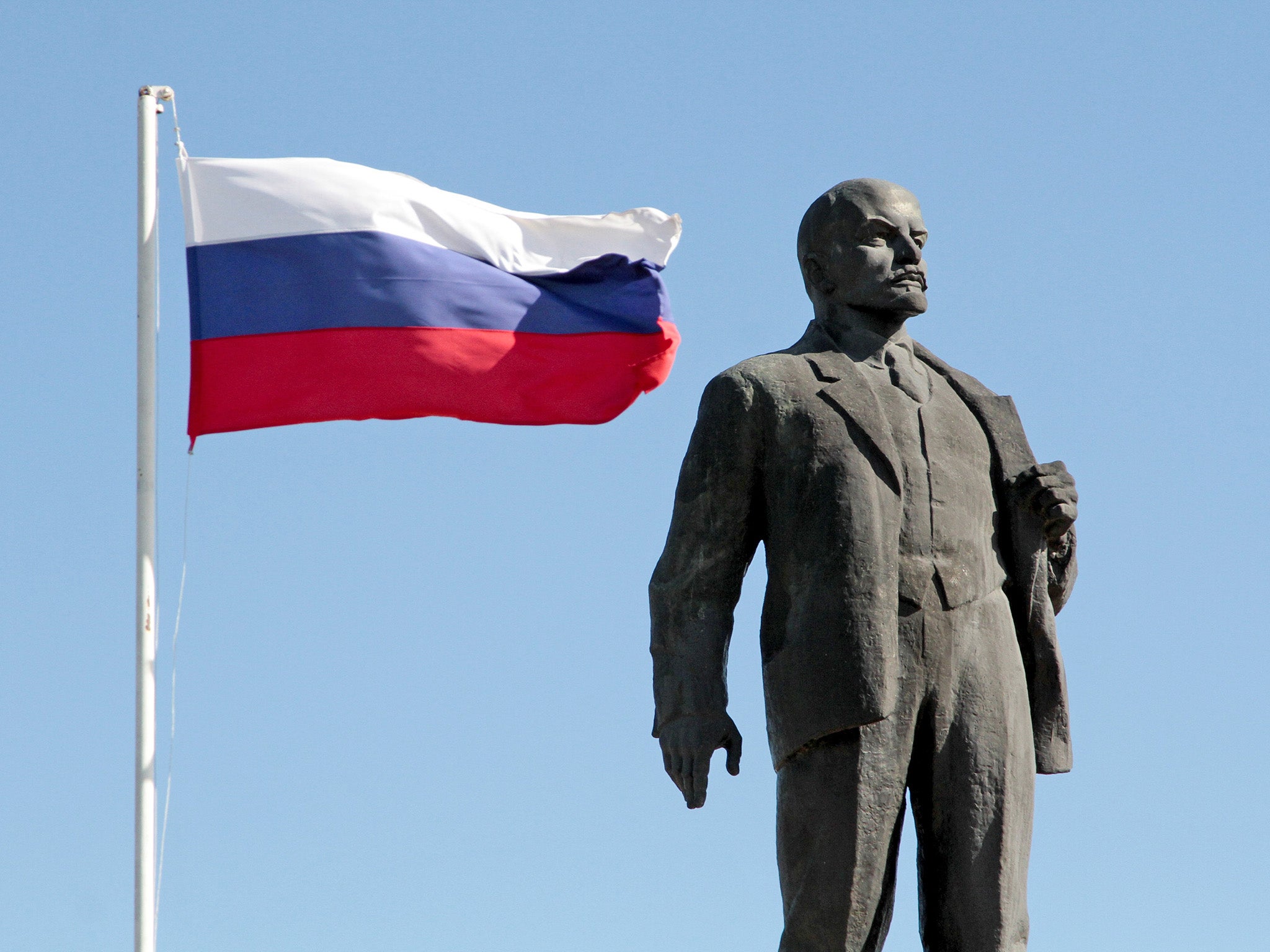

What seems like a new tactic of persuasion nonetheless dates back to the 1917 Russian Revolution. The new government led by Vladimir Lenin had to convince the starving population to follow them, thus the “propaganda state” was born. The Bolsheviks used the Russian rail network to make their propaganda accessible to large, often illiterate, audiences Compare this to the digital networks that send images to billions in a fraction of a second. Punchy, colourful, graphic posters with catchy slogans are the grand-grand-grandparents of the language of memes and gifs as we know them.

Lenin focused on the masses and their struggles in his posters. Present-day internet trolls often pretend to speak on behalf of ordinary people. Similarly, the “troll” who posted the fake picture of a Muslim woman during the Westminster attack called himself @Southlonestar, “proud Texan and American patriot”.

It was Stalin who spread state propaganda outside of Russia by sending 7,000-8,000 articles in English to foreign press outlets. They ranged in topics, from “A Soviet Peasant is Studying” to “Sport for People’s Countries”, with catchy content like ‘Soviet government has increased and understood people’s interest in horses.’

The publications were often poorly written and did not bring much following to the Communist party. In the 50s and 80s propaganda found its voice with fake news being placed in non-Soviet media. Richard F Staar from Stanford University claims that “black” propaganda included clandestine radio stations on US territory and disinformation campaigns. Bogus documents were distributed: such as the fabricated US embassy report about a plan to overthrow the government in Ghana, and the fake Reagan speech to place 48 nuclear weapons in Iceland in case of war.

Under the ‘iPad president’ Medvedev, the internet brought a new dimension to Russian propaganda. The Kremlin not only controlled the national television, press and an array of loyal digital outlets – it now had a troll army. Staff were hired to pollute the conversations in Russian liberal blogs – leaving multitudes of hateful and meaningless comments. By the 2010s, propaganda spilled beyond the Russian-language internet – by 2016 90 staff members of the “troll factory” were working on the US elections.

Similar to the early days of the Soviet Union, when general literacy was all new, we now live in the early days of digital comprehension. The recent US election was inundated by memes and showed that these viral texts can trigger a change of opinion. When the supposedly Russia-based troll published a doctored image of a Muslim woman walking past the site of a terrorist attack it appealed to these “digital naives”. Stanford research and Pensylvania State University studies prove that people don’t check fake news. From school kids to adults, users take for granted most things they see online.

The Russian revolution is one hundred years old this year, yet the lessons of the people who had to rebrand the politics for population are more cogent than ever. It is not known whether internet trolls study Propaganda 101, but no doubt they do know how to employ the century-old tactics to affect the minds of Western publics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments