Russia’s recent invasions of Ukraine and Georgia offer clues to what Putin might be thinking now

Based on my military experience, Putin would not want to send large troop formations into Ukraine this year without some sort of justification, credible or not

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Given that Russia has amassed 100,000 troops along its nearly 1,200-mile border with Ukraine, a look at two recent invasions by Russia against neighboring territories offers insight to what a possible new invasion would entail if diplomacy is unable to ease the growing tensions.

Invasion of Georgia

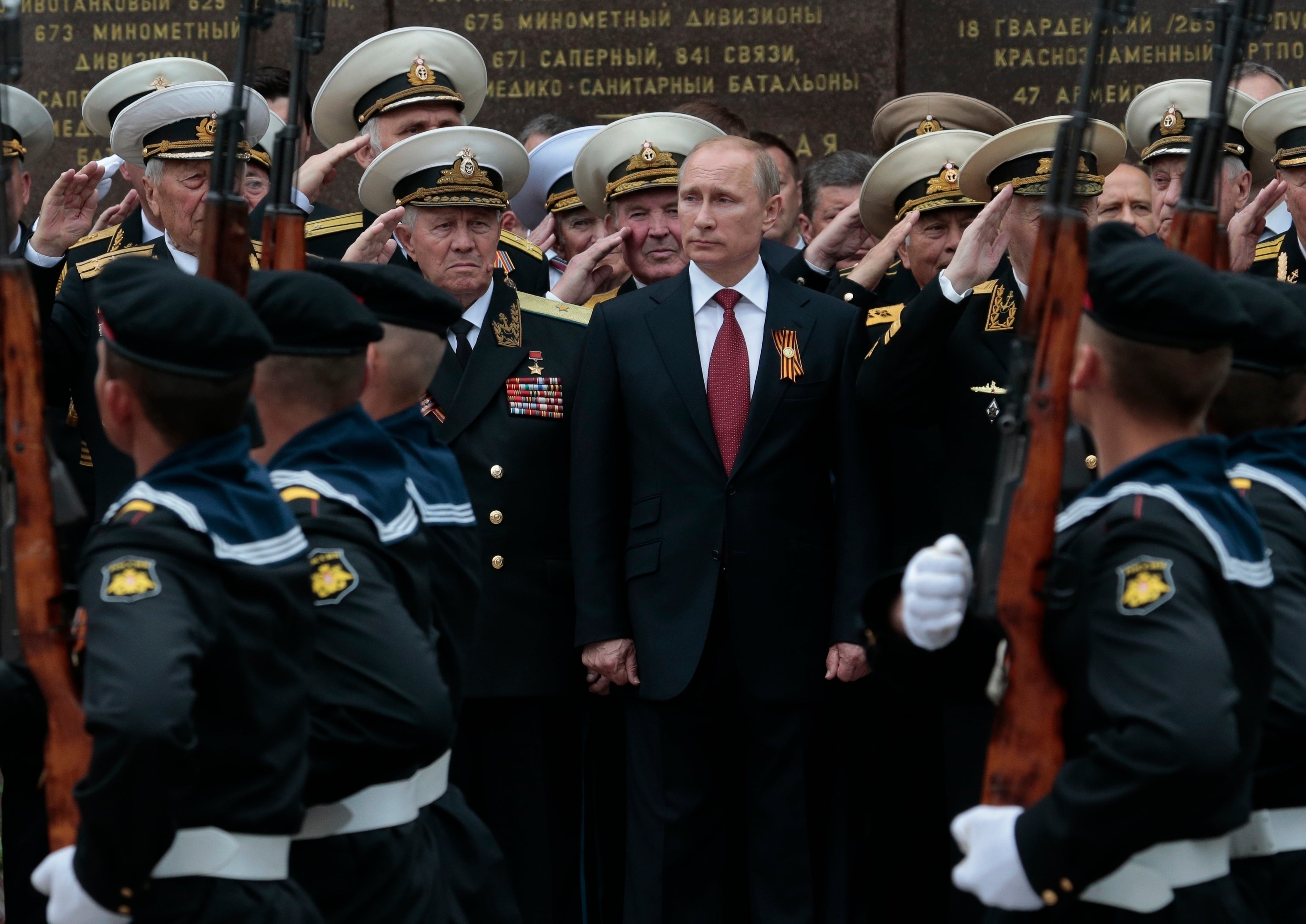

In 2008, Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia, a country in the Caucasus region located on the Black Sea, during the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. Approximately 40,000 soldiers and 1,200 armored vehicles entered into Georgia’s semi-autonomous region of South Ossetia before stopping about 35 miles short of Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital.

Putin attempted to justify the invasion under the pretense of the international norm of the responsibility to protect. In this case, Russia argued that its use of force was required to protect Osseitians from Georgian “genocide”.

Yet the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, a nongovernmental international agency started in 2008 to prevent genocide, found no legal justification for Russia’s use of force. Instead, there is plenty of evidence to indicate the war was “premeditated.”

Invasion of Crimea

In 2014, when Russian invaded Crimea, Putin had a large troop formation along Ukraine’s border. But instead of invading there, Putin used hybrid warfare to seize Crimea, a peninsula that juts into the Black Sea and housed a Russian naval base.

Ukraine failed to provide a military response. But when Russia actively supported separatists in the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk – collectively known as the Donbass – Ukraine fought back. Even though Ukraine’s military was in a “decrepit” state, hollowed out by decades of corruption, it was able to push the Russian-backed separatists to the border with the help of volunteers.

In response, Russia increased its support, sending small military formations to assist the separatists.

As a career U.S. special forces officer with combat and operational deployments in Afghanistan, Iraq, Bosnia, Africa and South America, I conducted field research on the 2008 and 2014 wars in Georgia and Ukraine. Based on my military experience, Putin would not want to send large troop formations into Ukraine without some sort of justification, credible or not. As it is now, justification for an invasion would be extremely difficult for Putin. That doesn’t mean he won’t invade anyway.

From what I have learned, I expect a possible Russian invasion would start with cyberattacks and electronic warfare to sever communications between Ukraine’s capital and the troops. Shortly thereafter, tanks and mechanized infantry formations supported by the Russian air force would cross at multiple points along the nearly 1,200-mile border, assisted by Russian special forces. Russia would seek to bypass large urban areas.

Likewise, Ukraine would seek to keep the major combat out of large urban areas to minimize the destruction. But neither side likely would be able to avoid urban fighting altogether.

A stronger Ukrainian military

It would likely be a limited incursion. The political cost of capturing Ukraine’s capital would be too high, and as a result, Putin would likely stop short of Kiev, just as he did with Tbilisi during the invasion of Georgia in 2014. But the war would be extremely costly for Russia because of significant improvements in the Ukrainian military since 2014.

In 2008, a less sophisticated Georgian Army shot down as many as 22 Russian aircraft, causing Russia to significantly decrease its sorties. Russia would likely meet the same fate in 2022 against a Ukrainian military armed with Stinger missiles that are being transferred from Lithuania and Latvia.

After testing Ukrainian air defenses and suffering losses in the first few days, I suspect Russia would largely ground its aircraft and instead rely on multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) to knock out strategic strongholds.

Ukraine also would likely keep its air force grounded, just as it did in 2014, leading observers to question why Ukraine maintains an air force that costs billions of dollars if it fails to employ it in war.

On the ground, Russian tanks also would likely face a much different defense. In 2014, for instance, Russian T-90 tanks supporting separatists in Ukraine’s Donbass region were almost impenetrable. Since then, Ukraine has upgraded its defense. In 2017, the United States provided Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, with additional missiles arriving from Estonia in the coming days. These man-portable, self-guided missiles are extremely accurate, extremely effective, easy to use and would inflict heavy losses on the Russians.

Ukraine’s military is far more capable now than it was in 2014. Since then, the United States has committed over $2.7 billion in training and equipment that has helped reform Ukraine’s defenses. Ukraine’s military is now at least on par and most likely better than the Russians at the tactical level, which is similar to 2008 when Georgian forces often outperformed their Russian counterparts.

When Russia invaded the Donbass, Ukrainian “volunteers” flocked east to stave off Russian forces, preventing Ukraine from losing more than just the Donbass. Many were completely untrained, yet they fought well. Over the past few years, volunteers have continued to train.

Russia would not have the element of surprise as it did in 2008 and 2014. Instead, it would find a ready and trained volunteer force that would provide not only critical intelligence to the Ukrainian military but also counterattacks against Russian forces during the invasion.

A high price to pay

Despite the advances of the Ukrainian military, Russia’s military, due to its sheer size, would still overwhelm the Ukrainians.

Yet a military victory would come at an extremely high military and political cost. Sanctions against Russia following its seizure of Crimea in 2014 have been estimated to have reduced Russia’s economic growth by 2.5 to percent, or roughly $50 billion per year. Sanctions would likely be much more significant this time.

It is doubtful that Putin is willing to accept these costs. With additional Javelin and Stinger missiles being sent to Ukraine from Western allies and messaging from President Joe Biden that Russia would “pay a heavy price” for any invasion, Putin might heed the warnings.

Liam Collins is the Founding Director of the Modern War Institute at United States Military Academy West Point

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments