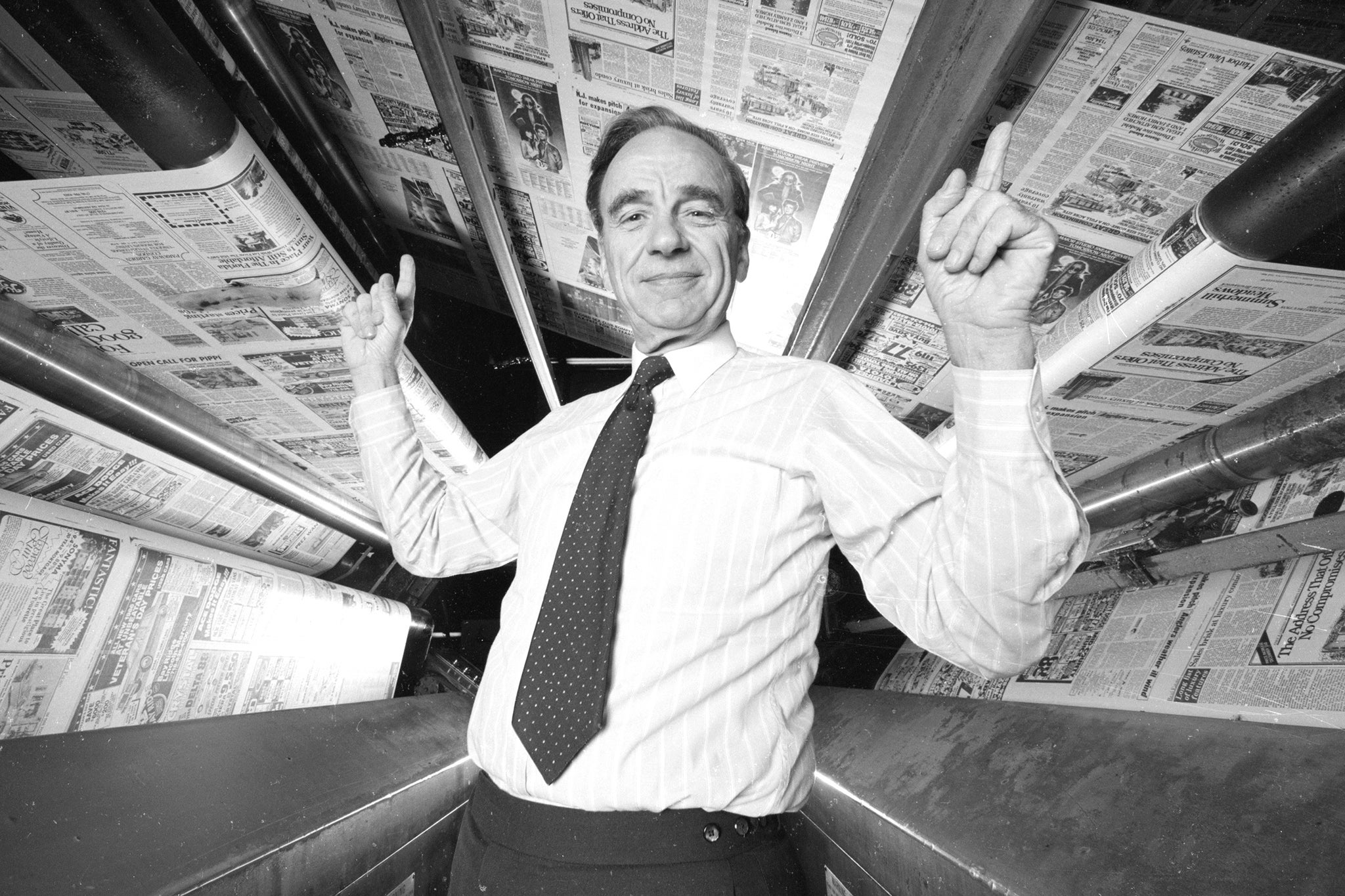

How Rupert Murdoch tried to kill off The Independent with his ‘10p Times’

In the 1990s, the Times proprietor sparked a vicious price war among Fleet Street newspapers – and its baleful effects are still felt today, writes Sean O’Grady

Of all the reasons to despise Rupert Murdoch – and there are many – mine is personal: he tried to kill The Independent.

I fully accept that it was only thanks to the way that he had smashed the print unions and brought new technology into the newspaper industry 40 years ago that The Independent could even get started – but that’s no excuse for his attempted Indy-cide, if you’ll pardon the expression.

So, yes, I’m extremely happy that he’s left the media stage. Despite the defiant resignation letter he issued on Thursday, the world’s most malign 92-year-old has been, in the words of biographer and close observer Michael Wolff, a “barely functioning” boss of his corporation for some time. And, as you see from the now-digital organ in your hands, we’ve survived his predation.

Thirty years ago – when buying a newspaper (they weren’t called “print” newspapers then because there was no other variety) was ordinary, rather than a special treat – The Independent had made a storming entry into the broadsheet market with its 1986 launch: fresh, innovative, inspired and embodying attractively liberal social and economic values. By 1992, circulation had risen to 440,000 – extremely high by contemporary standards at the “quality” end of the market.

Then it overtook The Times, Murdoch’s flagship.

Sweetest of all for those of us who had been loyal to the title from day one, it was precisely because of The Times’s slavish and tedious loyalty to the Conservative party that the more... well, independent-minded upstart was nicking readers from it.

So in the mid-1990s, Murdoch launched a price war to try and give himself a market share he didn’t deserve. His intention was to drive The Times’s other broadsheet rival, The Daily Telegraph, out of business – but if The Independent went down the drain, too, so much the better.

In 1994, when Murdoch dropped the cover price of The Times from 45p to 30p, it sparked a Fleet Street price war that endured for two years, after which there was a bit of a truce. Then, in 1996, he started a new, even more vicious offensive, selling The Times for 10p, virtually giving it away. In the end, Murdoch’s blatant attempt to weaken his competition and put other papers out of business became so obvious the supine Office for Fair Trading stepped in to end the trench warfare.

I well remember the Price Wars, though I was only an Independent reader at the time. And I actually liked the “10p Times”. It was so cheap, I could afford to buy it as a second newspaper (obviously, I kept reading The Independent as usual as well…). There was another bonus that, with every copy of The Times sold, Murdoch would be losing money.

At the time, The Independent’s management’s response was, if not panicky, uncertain. The Indy, always quirky, at first responded to the Murdoch price-cutting initiative by actually increasing its own cover price – an amusingly defiant move designed to assert the loyalty of The Independent’s individualistic tribe of readers and support the quality of its journalism. That wasn’t entirely successful commercially, so the price eventually went back down. For one day only, it was even cut to 20p – five pence lower than the launch price a few years earlier.

“Predatory pricing” is an old tactic, and hardly confined to newspapers, but, because of their profile and the egos of their owners, media price wars tended to bigger stories. Murdoch had already slugged it out with Lord Rothermere and Robert Maxwell in the London market a few years before, using cheap or giveaway papers to try to destroy the opposition. This was Murdoch’s favourite pose, as the risk-taking disruptor of a cosy status quo.

In reality, though, predatory pricing is a crude and unfair trading practice, and nothing to do with producing a competitive product. It’s a war of attrition in which the player with the deepest pockets wins; the one who can survive the financial losses for longest gains an undeserved market dominance. It also happened with buses in the 1990s, when the government deregulated local transport.

Despite faithful shareholders, The Independent couldn’t match Murdoch’s financial resources. But things were also “personal” because, at the time of the Wapping strike, the Indy had recruited a number of brilliant journalists from The Times – including “refuseniks” such as Robert Fisk, who was part of the core start-up operation that took on his former newspaper.

I wish I’d been one of that pioneering band led by founding editor Andreas Whittam Smith, but by the time I joined The Independent in the late 1990s, the price wars were over. Lasting financial harm has been done to the sector and, regrettably, Murdoch’s baleful influence over British journalism has persisted until today.

In the resignation statement he put out this week, he wrote how “the battle for the freedom of speech and, ultimately, the freedom of thought, has never been more intense”. Some of us might point out that his efforts to close down other profitable newspapers, and the platforms they offered for freedom of speech, had been pretty intense – and that there were no winners. In that era, The Independent was as much the disruptor of the existing newspaper publishing establishment as Murdoch was.

Murdoch likes to think himself a man who “gives the public what they want”. But when The Independent came along and did that better than his Times, he didn’t like it. Rather than up his game, he tried to bankrupt us. As Whittam Smith wrote in 1994, in the midst of the price war, the existence of The Independent is, and will, remain a challenge to the likes of Murdoch and his cynical vision of the role and purpose of the media.

Despite Rupert Murdoch’s best efforts, we’re still standing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks