Decades ago, I was taught law by a famous right-wing judge. He was an extremist — but at least he was honest

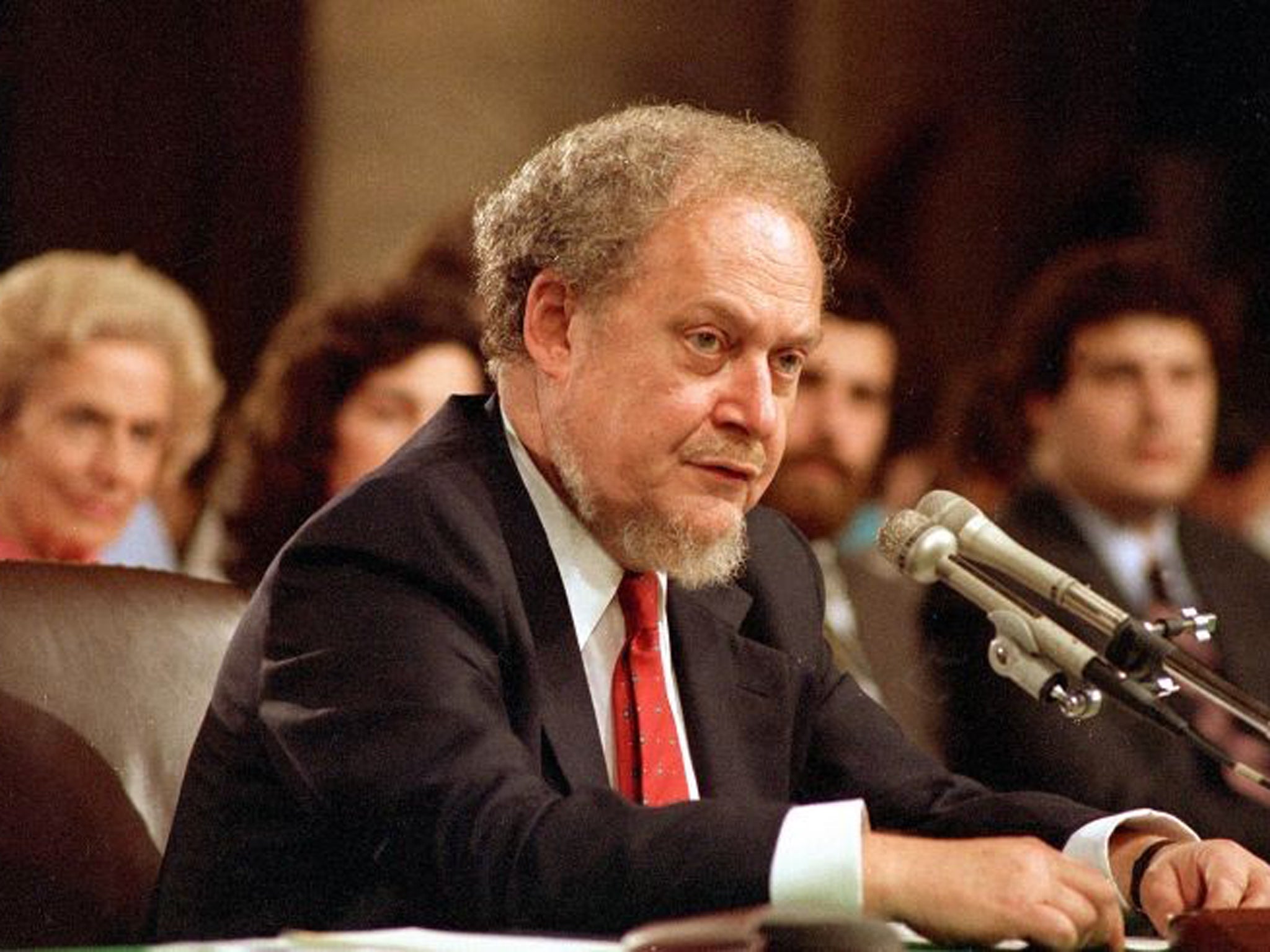

Robert Bork shared views with people on the Supreme Court today. As a liberal, I disagreed with everything he had to say, especially where it concerned Roe v Wade and Brown v Board of Education, but it gave me a valuable insight into the psyche of such judges

When I was in law school, Robert Bork, already an appellate judge, taught a seminar on judicial review. He was already rehearsing his answers for his widely anticipated Supreme Court nomination hearings. His views were extreme, but he was rigorously honest, quite unlike today’s Supreme Court majority that shares his extremism but lacks his candor.

Bork knew that he needed to support the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. He was uncomfortable with the Court’s considering an abstract principle that he viewed as neutral — “separate but equal” — and then looking outside the marble columns to see how “separate but equal” was being implemented throughout the states. He was skeptical of a court infusing sociological data into decisions that were supposed to be made on legal principle alone. Yet he also knew that whatever the Brown Court’s reasoning, there was no principle of morality or justice that could take us back to segregation.

Bork was partial to the idea of “Constitutional easements”: decisions which may have been on shaky jurisprudential ground, but over time had become so fundamental to the American way of life that they could not be overturned without serious disruption to American society and culture. At that time, Brown had been the law of the land for less than thirty years, but he knew the Court could not order resegregation of American schools.

Ironically, America’s schools remain heavily segregated nearly seventy years later. Desegregation of schools may have been a “super-precedent,” but essential patterns of American life had not accreted around that principle. Desegregation, over massive white resistance, proceeded during the 1960’s, but segregation of Black children in schools has changed little since 1972, during which time segregation of Hispanic children has increased. Since then, the promise of Brown has regressed. Courts have abandoned comprehensive remedies unless it can be shown that segregation is intentional rather than reflective of residential or income patterns. Today, Black children are five times as likely as white children to attend schools that are highly segregated by race and ethnicity. Bork’s Constitutional easement does not exist in real life.

As one of the few token liberals in that seminar, I asked Bork, “Roe v Wade is now ten years old. When will patterns of American life with respect to reproductive rights grow up around Roe so that it creates a Constitutional easement?” Never, he answered.

He was right. For nearly fifty years, women’s right to make their own reproductive decisions were Constitutionally guaranteed. One could argue with the reasoning of the majority opinion in that 7 to 2 decision, but it was the law of the land and generations of women (and men) grew up in a country where abortion was up to the woman who was pregnant, not the state. As with desegregation, the right was controversial and subject to debate, protest and even violence. Patterns of American life about the most difficult and intimate issues that people faced in their lives — teen pregnancy, pregnancies that were the result of rape or incest, whether to proceed with a pregnancy with a severely ill fetus or one that was incompatible with life, whether couples could afford to raise more children — became decisions made by women. Ten-year-old rape victims could not be forced to carry a pregnancy to term because the state insisted on invoking its moral preferences. Poor women, frequently of color, did not have to travel hundreds of miles and incur costs they could not afford to incur because wealthy, largely white male legislatures decided that their political calculations or moral hunches should be imposed on everyone. For half a century, despite numerous attempts to curb and qualify that right, women controlled their bodies, not the state. Social patterns arose around that reality.

While it is difficult to get completely reliable statistics, the Guttmacher Institute estimates that there were approximately 750,000 abortions per year just after Roe, rising quickly above one million and peaking at about 1.5 million per year in the early 1990’s, after which there has been a slow and steady decline to just under one million in the most recent statistics from 2019. Whatever one’s views on abortion, there can be no doubt that these most difficult, intimate decisions have been made by tens of millions of American women. And now, they will not.

With the decision in Dobbs, states now make that choice; they can accord rights or deny them as they choose. Thirteen states have “trigger laws” that were passed to take effect immediately or shortly after the overruling of Wade. Some states never repealed their abortion laws, despite their being made unenforceable by Roe. Wisconsin’s law, written in 1849, makes providing an abortion a felony, with penalties of up to six years in prison and a fine of up to $10,000. Michigan is debating reinstituting a 1931 ban. Neither state has exceptions for rape or incest. Idaho’s law makes no exception to save the life of the mother. Can it really be seen as democratic and respectful of women that states are dusting off statutes that were passed by legislators who were no doubt all male and now all dead?

But the issue goes beyond dead-hand control by legislatures that made laws under different conditions and in different societies. Legislatures today, often gerrymandered and unrepresentative, have passed and will pass similar laws. Many states are vying for who is most categorically inflexible on abortion. And if Republicans take control of the federal government in 2024, there may well be a categorical prohibition nationwide.

It’s been argued that if abortion rights are so important, presumably the voters will take steps to make these rights available. But that is a naïve view of the current American system, which has become sclerotic, polarized and unrepresentative of the will of the majority. I fear that women will look back to the time when their wombs were their own, not the property of a reactionary and unresponsive political system empowered by a Supreme Court truly “rigged” by Trump and his enablers.

Eric Lewis is a human rights lawyer. He sits on the board of The Independent

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks