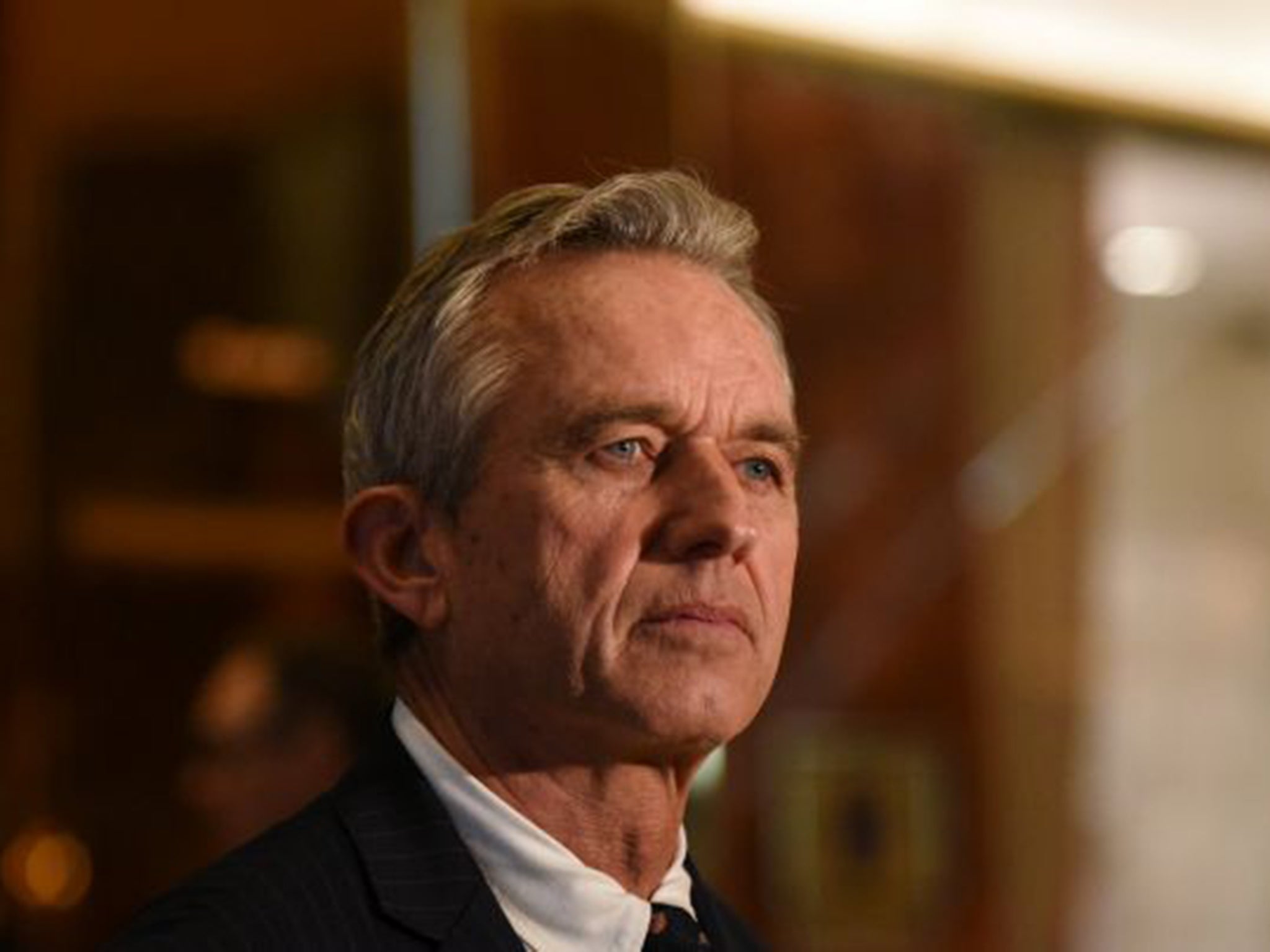

Robert F Kennedy Jr’s Instagram ban proves the left has a problem with conspiracies too

Kennedy is a member of Democratic royalty, yet he has been spreading anti-vaxxer conspiracy theories during a pandemic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Yesterday, Instagram permanently removed the account of a prominent anti-vaccine activist. Perhaps to your surprise, it was not some deranged far-right QAnon nut. It was that scion of Democratic royalty, Robert F Kennedy Jr.

Kennedy, the son of former US Attorney General and Senator Robert F Kennedy, has a history of peddling anti-vaccine conspiracies. So ridiculous and misleading are his views that in 2019, his own family wrote an op-ed criticizing him. Now, apparently, he has gone too far even for Instagram, a site owned by Facebook, itself a company with a reputation of being slow to address misinformation. "We removed this account for repeatedly sharing debunked claims about the coronavirus or vaccines," a Facebook spokesperson told CNN.

What is interesting about this incident isn’t that Kennedy is “vaccine-hesitant”. Rather, it is that he isn’t a Republican. He isn’t even right-wing. He is, by every other measure, a consistent left-wing activist, particularly on the issue of climate change.

Ever since Donald Trump began labelling every piece of journalism he didn’t like “fake news,” we have seen endless media coverage about the political right’s descent into an orgy of misinformation and lies. From QAnon to Pizzagate to “The Big Lie,” it often seems like the American right is living in an alternate reality. Yet the uncomfortable truth is that fake news and conspiracy theories have never been the sole purview of folks in red hats and sinking flotillas. This is a problem on the left, too.

Take election fraud. Studies found that before the 2016 election, Democrats showed higher levels of trust in election integrity (though marginally). After the election, however, Democrats tended to believe the election was rigged while Republican belief that the election results were sound increased. It is something dubbed “the winner’s effect,” where the losing side becomes more skeptical of the results. And Republicans were not wrong when they said some Democrats refused to accept the 2004 election results. As Politico reported last year, there is still a group of left-wing activists who insist Ohio was rigged for Bush.

Now, before you blow up my mentions with “but no one on the left is storming the Capitol to overthrow the government,” that is quite obviously true. I am not arguing the scale of the problem is the same on the left as it is on the right, nor that left-wing conspiracists are as dangerous as the “Stop the Steal” insurrectionists. But no one can seriously contend that disinformation and conspiracies do not infect the left, too.

As The Guardian reported in 2017, “on the left, there are numerous styles of misinformation that appear to be gaining traction,” including “deceitful and hyperbolic headlines, viral memes that have a very tenuous connection to the truth, and poorly sourced articles that use inaccurate visuals to draw readers.” This assertion was bolstered by a 2020 survey conducted jointly by the left-wing Center for American Progress and the right-wing American Enterprise Institute. The findings show that a majority of Americans believe either debunked or unproven conspiracies, though — unsurprisingly — which conspiracies those are varies between the right and the left.

This isn’t just an American problem, either. A 2018 survey showed that 60 percent of British people believe in some form of conspiracy theory — and not all of them are right-wing. Just last month, a quote purporting to be from Boris Johnson, claiming that he wished he were born in the Middle Ages so he could spend his days “lopping the heads off of smelly peasants and then giving the stable boy a jolly good buggering” went viral. It took all of 30 seconds of Googling for me to debunk it, but as of today it has over 700 retweets.

I was able to immediately clock that Johnson quote as being false because I understand how social media works. I was skeptical of a quote I had never encountered imposed on a graphic that looks like it was created in Microsoft Paint, that was just outrageous enough to attract attention but not so outrageous that it would automatically be dismissed, especially given the British prime minister’s history of making outrageous and offensive comments. But hundreds of others, including people I know and respect, were not.

A simple but painful fact is that the American and British people both lack a fundamental media literacy, and that includes social media. The internet has changed the way in which people consume news and information, but we have not taught our citizens the basics of how to navigate this Wild West of disinformation and how to tell a credible source from an incredible source. Couple that with a growing ignorance in how laws are made and government functions, and you have a perfect storm for conspiracy theories.

The only way we can counter this is to teach our children basic civics and media literacy — including social media literacy — from an early age, and to revamp our curricula to address ongoing misconceptions in everything from history to science.

This is not a right-wing problem or a left-wing problem. It is a global problem, and one that is not going away. We need to stop politicizing disinformation and conspiracy theories and start taking them seriously before we lose another generation to fake news.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments