I was stuck in the British asylum system for four years – I’m deeply concerned about the Nationality and Borders Bill

When I became a refugee, I was separated from three of my children for 1,460 days. I counted every single one

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I became a refugee, I was separated from three of my children for 1,460 days. Each and every day I thought about them constantly, worrying about whether they had enough to eat and hoping that they were safe.

I was stuck in the British asylum system for four years, waiting for the Home Office to grant my youngest daughter and I refugee status. During this time, I had no choice but to leave my three eldest children in Nigeria, where they were looked after by my mother.

After years of waiting, in the moment we were reunited, I finally felt alive again – I was so very happy. I felt the joy of knowing that my children were safe, here with me, at last.

I come from northern Nigeria, where female genital mutilation (FGM) is still common. My grandma, my mum and I all went through it – I was only eight when I was mutilated by a group of older men and women. I could not go to school for three months. I got an infection. I couldn’t walk. But life went on. I went to university and became an accountant. I had three children. We had a good life.

In 2014, I had the opportunity to come to the UK to study accounting at Southbank University. During this time, I became pregnant with my fourth child – a girl. I knew straight away that if she grew up in Nigeria, she would be forced to undergo mutilation the same way I had been. I couldn’t allow it.

That’s when I realised I had no other choice but to claim asylum in the UK to protect her. I thought that this would be an easy process, that I would be reunited with my three other children soon. But it was just the start of a painful journey that lasted four years.

Four years of being apart from my children, four years of waiting every single day for a decision on my application from the Home Office. These were very difficult years. My daughter and I had to rely on charities like Praxis to survive, because – though I am a qualified professional – I wasn’t allowed to work while our asylum application was with the Home Office.

All this time, I was constantly worried for my other children still in Nigeria. Even though they were with family, other people were taking advantage of them. They weren’t going to school because they were being forced to look after other people’s children – to wash plates and clean homes. They weren’t being fed properly. They were treated like servants by my extended family, and there was nothing I could do about it.

Every time I ate I would think about my children not being able to eat. I couldn’t sleep not knowing what was happening to them.

Now that they are here with me, my mind is at rest. I can see that now they have me by their side, they are blossoming. I sit down with them every day, I help them with their homework, and talk to them as a mother. I wake them up in the morning, I give them a hug and a kiss. It took us four years, but at last my family is reunited.

As someone who could protect my daughter by claiming asylum in the UK and reunite with my children after my claim was recognised, my heart breaks for the families who might not have the same chance in the future. But unfortunately, that’s exactly what the government’s Nationality and Borders Bill will deny other families if it becomes law.

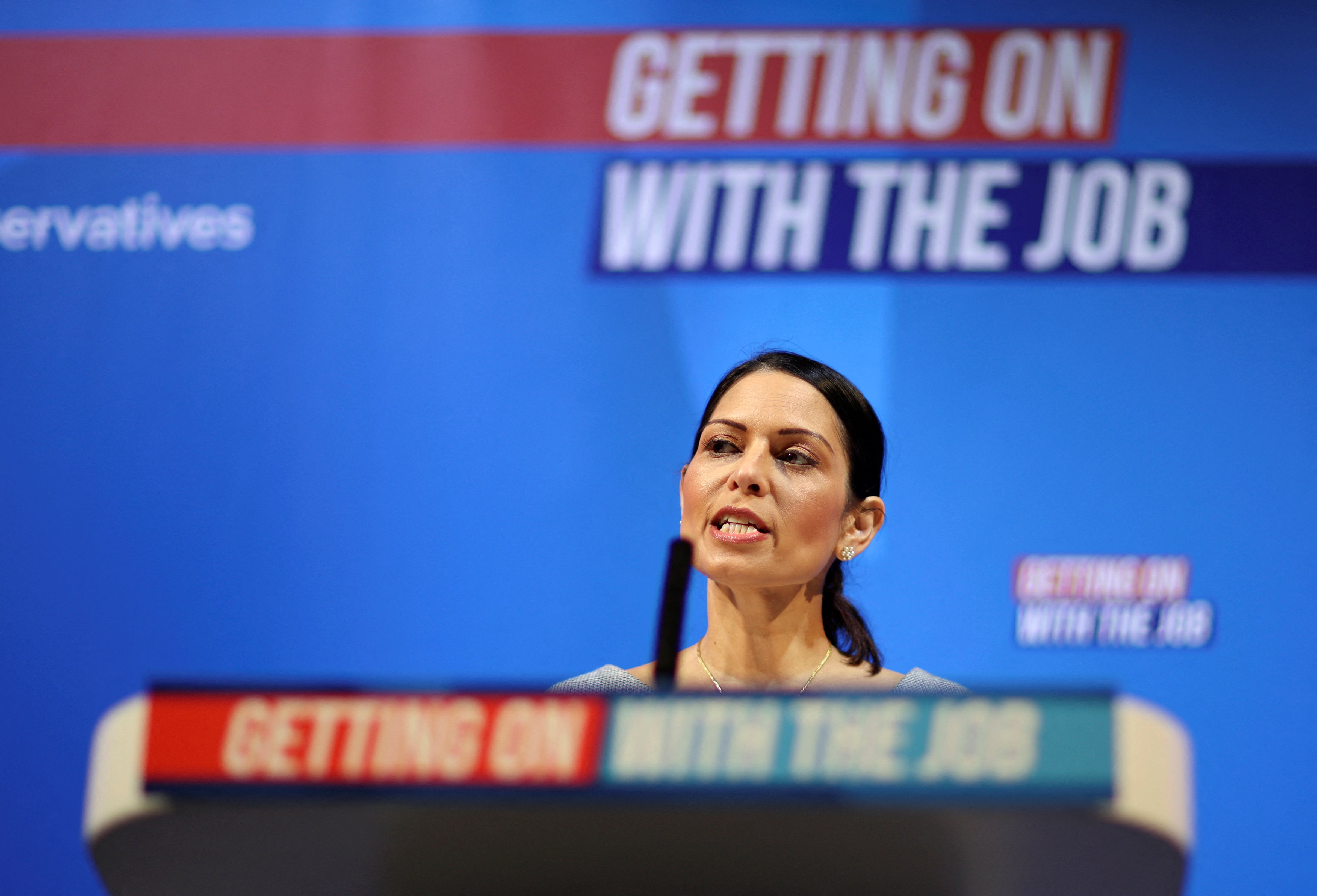

The government justifies the Bill – which is going back to MPs tomorrow – by saying it will discourage people from taking dangerous journeys, but it doesn’t offer any safe ways to get to the UK to claim asylum, no matter what threats people are facing.

Instead, it divides refugees into two groups: people who arrive in the UK via almost impossible to access “regular routes”, like government-approved refugee resettlement schemes; and everyone else, who will have no other choice but to embark on perilous journeys, crossing deserts and seas in search of safety.

For people like me, escaping the violence of FGM, there is no government-approved route to safety. I was lucky enough to come to the UK on a study visa, but a lot of people don’t have that chance. After the Bill becomes law, a mum afraid for her daughter will have no choice but to get in a small boat to find safety – often having to leave behind her children, just like I had to do.

Worse still, once that mum arrives in the UK, the Bill makes it much harder to prove that she is a refugee – something that will be especially hard for women who have fled their homes because they are afraid of gender-based violence. Even if that mum is recognised as a refugee, her problems won’t end there.

If she’s travelled to the UK outside a government programme, she’ll be given fewer rights than other refugees. Specifically, the Bill will take away her right to reunite with her children in the way I did. Having spent four years apart from my children, I know the pain and suffering that not being together causes.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

The thought of having to choose between returning to Nigeria and putting my daughter in danger or not being able to see my other children again makes me feel sick. It’s a choice that no parent should ever have to face. But it’s not too late to stop the Nationality and Borders Bill.

When members of the House of the Lords debated the Bill earlier this year, many showed great concern for the women who might struggle to claim asylum, and the families that won’t be reunited if the Bill becomes law.

They supported amendments that will ensure that refugees are not discriminated against based on how they reached the UK. Now, MPs have to vote on whether to accept these amendments.

As a mother who was separated from her children, I plead with MPs to stop this Bill, and ensure that families and children can live in safety and dignity – together.

Kemi is an accountant, charity worker and an advocate for the rights of refugees. She is a trustee at the migrant rights charity Praxis

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments