Pity the young: they’ll live to 120 and work until they’re 100

The profile of the workforce is changing: middle-aged people are losing their jobs to either robots or young people who have a more intuitive understanding of technology

I got my first job at the age of 19 and I am lucky enough to have been in full-time employment ever since. I have had two careers – not including a summer selling crimplene on the markets of northern England – and now I am approaching the point in my life’s journey when I should be contemplating a quieter, less pressurised, more liberated existence.

I hesitate to use the word retirement, because that suggests a disengagement with working life and a future of tending geraniums, going on cruises and complaining about young people, none of which I can quite imagine for myself. I may not have a choice in the matter, and I am preparing to embrace my impending obsolescence with relative equanimity. That’s because I know how fortunate I am to have been born when I was. When it comes to a working life, today’s children face a considerably more exacting, less secure and altogether frightening future.

According to Rohit Talwar, a respected futurist and strategic adviser, a child born today might live to be 120 years old, will work until the age of 100 and could have 10 careers within that time. This was the message he delivered yesterday to the annual Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference, and it sounds to me every bit as nightmarish as the polar ice caps melting or mutant organisms taking over the world.

Talwar’s contention is that advances in medical science mean that the average person’s life expectancy is extended by five months every year, and at the same time the growth of automation will significantly reduce the number of jobs available for humans. His message to Britain’s headteachers was that today’s schoolchildren should be better prepared for this rapidly changing set of circumstances.

“New industries coming through are going to be highly automated from day one,” he said. “If you walk around a Tesla factory, you can’t spot the human … You go to an Amazon warehouse now, there are no humans.”

So how to prepare young people to survive this perfect storm of many fewer jobs and much longer life expectancy? Mr Talwar says that children are educated today with an end goal in sight, like becoming a computer programmer or a biologist. “But we are not sure the jobs will be there when they come out,” he adds. He believes that “life skills” – learning how to meditate, avoiding stress and emphasising the importance of sleep – should be taught in schools.

He’s right, of course, even if we might question the detail of his projections. The world of work is changing more rapidly than we can even imagine. We can’t picture the next big technological invention that will revolutionise our lives, but we can be sure there will be one.

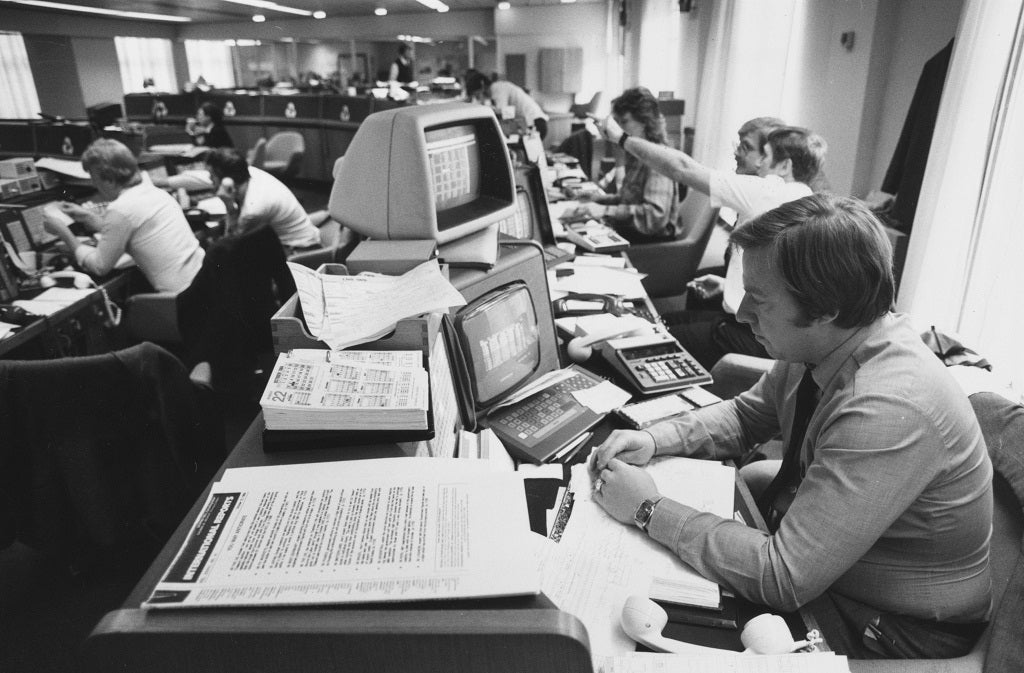

Already, the profile of the workforce is changing: middle-aged people are losing their jobs to either robots or young people who are cheaper and have a more intuitive understanding of technology. This trend will only increase, and the age of those who have become obsolescent will get younger.

Talwar has shone a light on something that may be difficult for us to comprehend. We are living through a new industrial revolution, and no one truly understands where it will lead us. We of a certain age are the lucky ones.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks