The artist as avenging angel: How Paula Rego reshaped a nation’s view on abortion

Rego depicted women kneeling and lying down in backstreet clinics, to highlight the fear, pain and dangers of making abortion illegal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

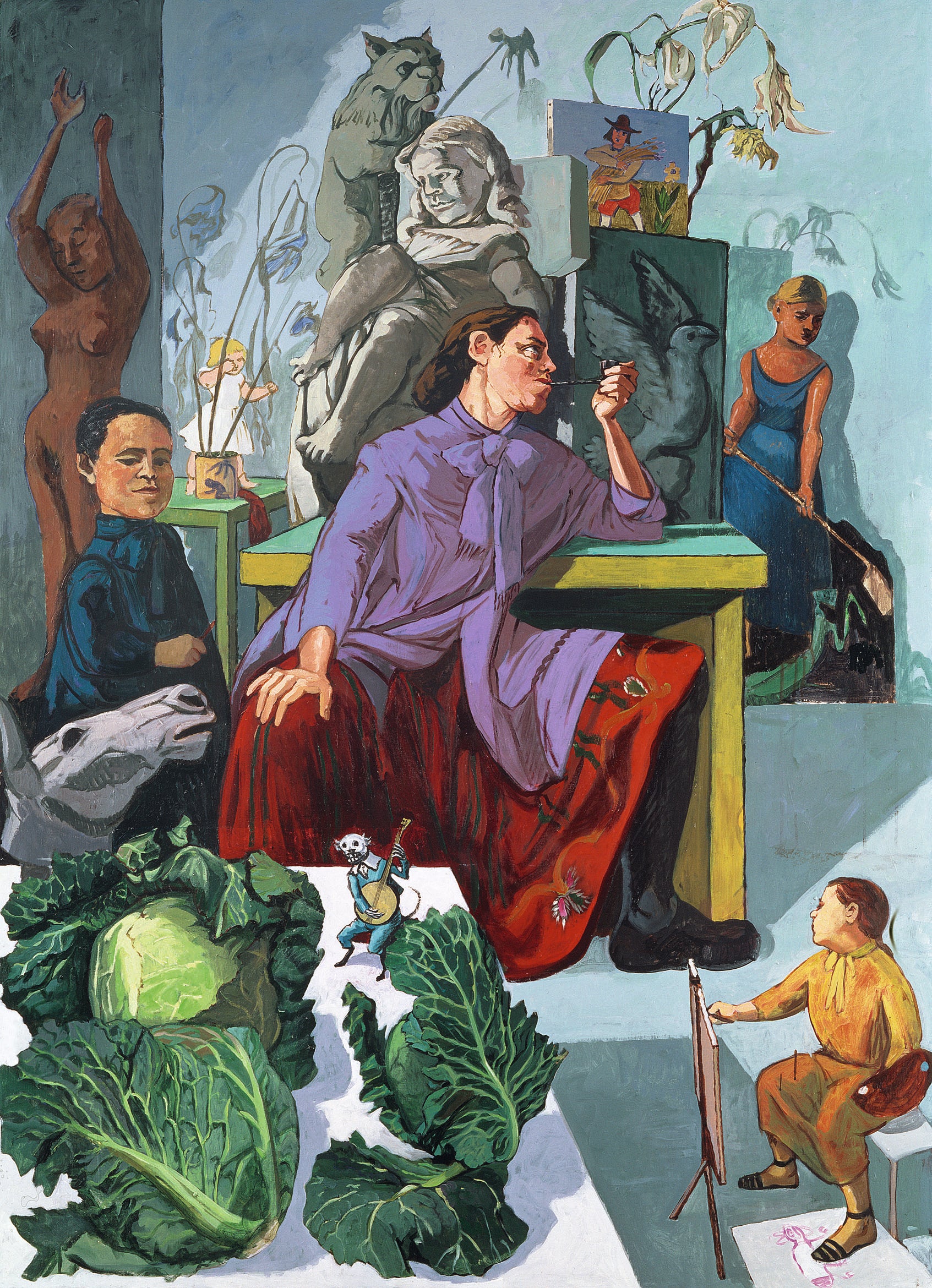

Your support makes all the difference.Dame Paula Rego, who has died aged 87, painted The Artist in Her Studio in 1993. This symbolic image depicts a seated sculptor, legs splayed, smoking her pipe.

Challenging romanticised images of the genius male artist in his studio, it asserts Rego’s right to be celebrated alongside the great masters, while presenting her as a decidedly subversive and feminist storyteller.

From the start of her career, Rego used fiction to tell uncomfortable truths and tackle taboos. Born in Lisbon in 1935, she grew up in a Catholic country, under the dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. In her paintings, collages and drawings from the Sixties and Seventies, Rego fiercely opposed fascism, poking fun at the dictator in works such as Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) in which he has been reduced to an abject, abstracted figure.

In 1951, Rego arrived in the UK, where she attended finishing school before securing a place to study painting at London’s prestigious Slade School of Fine Art. It was here that she met fellow artist, Victor Willing, whom she married and had three children with.

Willing also became the subject of her boldly painted series “Girl and Dog” (1986–87), in which sturdy dark-haired girls in pretty dresses nurse a sick dog. Through the lens of fiction, Rego was exorcising her own grief – she had become Willing’s carer, as he suffered from multiple sclerosis, before passing away in 1988.

But much more of Rego’s art has illuminated the plights of other women. In 1998, a referendum to legalise abortion in Portugal failed, and Rego created one of her most formidable bodies of work, the “Abortion Series” (1998). Collaborating, as she often did, with her main model Lila Nunes, she depicted women kneeling and lying down in backstreet clinics, to highlight the fear, pain and dangers of making abortion illegal. The effect of these visceral images was so powerful that they were credited with helping sway public opinion to form a second referendum in 2007.

In other series, Rego confronted sex trafficking, honour killings and female genital mutilation, speaking out, again and again, against the abuse of women’s bodies. But her characters appear as survivors, not passive victims, often triumphantly gazing at the viewer or at one another. As the artist once declared: “I prefer a heroine to a victim any day”. She reclaimed femininity as something quite ferocious.

Frequently taking inspiration from Portuguese folklore, myths, fairy tales and nursery rhymes, Rego recounted these narratives from a female perspective and with strong Freudian undertones. In her nightmarish Neverland, Snow White straddles the prince’s horse solo, Little Red Riding Hood’s mother kills the wolf, a muscular mermaid drowns Wendy in a black lagoon and Little Miss Muffet meets an enormous, anthropomorphic spider.

Among the artist’s most empowered protagonists is the subject of her magnificent pastel drawing, Angel (1998): dressed in a dramatic floor-length golden silk skirt, a broad-shouldered woman stands assertively with a yellow sponge in one hand, and a glinting silver sword in the other. “Why is she smiling?”, viewers are left wondering.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

This picture was inspired by the Portuguese novel, The Crime of Father Amaro, in which a priest gets his landlady’s daughter, Amelia, pregnant. Soon after their son is born, Amaro arranges for the baby to be killed, and Amelia dies from complications during the birth. He, on the other hand, escapes all consequences for his despicable actions. In Rego’s wicked retelling, however, a newly invented character, an avenging angel, has arrived to punish the priest and, by the look on her face, takes immense pleasure in it.

The art world has paid great attention to Rego’s dissenting stories. The artist received much well-deserved recognition during her lifetime. She was the first artist in residence at London’s National Gallery in 1990 and enjoyed major solo shows at London’s Serpentine Gallery in 1988, Tate Liverpool in 1996, Tate Britain in 2021 and Bristol’s Arnolfini in 2022.

This summer, a major retrospective at Museo Picasso Malaga will pay tribute to Rego. Among the artist’s characters to be included is the sword-wielding angel: although not a self-portrait, this protagonist does reflect the reckoning force of Rego, who explained her modus operandi: “Art is the only place you can do what you like. That’s freedom”. Through such powerful protagonists, kept alive on the walls of international museums, Rego’s voice and legacy will live on.

Ruth Millington is an art historian, critic and author of MUSE

‘Paula Rego’ is organised by Tate Britain in collaboration with Kunstmuseum Den Haag and Museo Picasso Málaga, and will run 27 April–21 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments