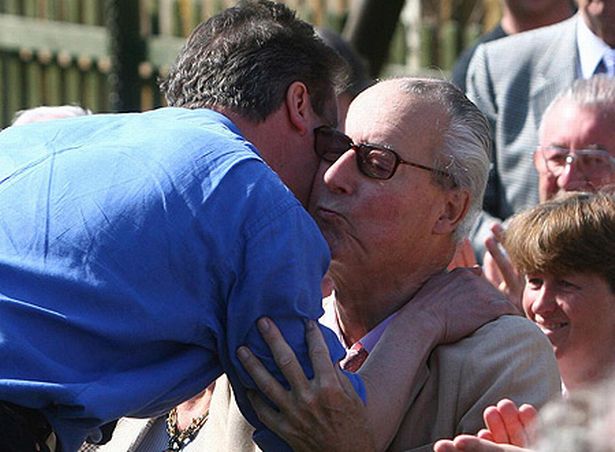

Panama Papers: what do they say, what does Cameron say, and should I be outraged?

Our Chief Political Commentator tries to answer the pressing questions about the disclosures about the Prime Minister's father's business interests

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What did the Panama Papers say about David Cameron’s father?

Someone must have done Ctrl-F “Ian Cameron” on the 2.6 terabytes of leaked documents, and found what The Guardian had reported in 2012: that the Prime Minister’s late father was a founding director of an investment company called Blairmore Holdings, registered in Panama.

The leak of documents from Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm that included Blairmore Holdings among its clients, provided a little more information. Blairmore was actually based in the Bahamas, although its decisions may have been made by Ian Cameron and his associates in London.

Richard Brooks, a Private Eye journalist and former HMRC tax inspector, said: “If HMRC had seen the papers they would have had some very serious questions. The clear intention for Blairmore was to avoid becoming UK tax resident and the test for this, even in 2006, is the location of the central management and control.”

On the other hand, many of Blairmore’s customers were not British, and it was legitimate for their investments to grow free of tax, but for them to pay tax when they brought their money home.

Ian Cameron was paid £12,400 a year as a director of Blairmore, and presumably paid UK income tax on it. When he died in 2010, he left £2.7m in his will. David Cameron inherited £300,000, while his two sisters split the proceeds of a £1m Kensington mews house between them.

What did David Cameron say?

In answer to a question from Faisal Islam, Sky News' political editor, after a speech about Europe on Tuesday, he said: “I own no shares. I have a salary as Prime Minister and I have some savings, which I get some interest from and I have a house, which we used to live in, which we now let out while we are living in Downing Street and that’s all I have. I have no shares, no offshore trusts, no offshore funds, nothing like that.”

Journalists pointed out that he hadn’t fully answered the question, which was whether “you and your family” had “derived any benefit in the past” or “in the future” from Blairmore Holdings, and phoned 10 Downing Street for more information.

So the Prime Minister’s press office put out a statement: “To be clear, the Prime Minister, his wife and their children do not benefit from any offshore funds. The Prime Minister owns no shares. As has been previously reported, Mrs Cameron owns a small number of shares connected to her father’s land, which she declares on her tax return.”

Again, though, nothing about possible past or future benefits – for example as possible beneficiaries of a discretionary trust. So on Wednesday, a spokesman provided a further statement: “There are no offshore funds/trusts which the Prime Minister, Mrs Cameron or their children will benefit from in future.”

Finally, then, that leaves benefits from Blairmore in the past, but it is obvious that Mr Cameron benefited indirectly from his father’s business, given that it didn’t go broke. The same applies to a fund, reported on Channel 4 News on Wednesday night, that Ian Cameron had based in Jersey. Again, that was reported in The Guardian in 2012, and presumably any interest in it that David Cameron might have inherited is onshore now.

Should I be outraged or not?

If Blairmore cheated the tax rules by pretending its decisions were made abroad, as Brooks suggests, it broke the law. But the evidence from the Panama papers is far from conclusive. It seems quite plausible that, as a sideline to his main job as a stockbroker, Ian Cameron merely took advantage of the lifting of exchange controls in 1979 to run an offshore investment fund, and that he did so entirely within the law.

Naturally, if you think that controls on global capital are desirable and possible, you might think that investment funds such as Blairmore should be shut down (Blairmore itself moved its operations to Ireland in 2012, after Ian Cameron’s death, and is now regulated under EU law). But it would be just as unfair to blame David Cameron for his father’s business choices as it was to hold Ralph Miliband’s Marxist beliefs against Ed Miliband.

The hullabaloo over the Prime Minister’s incomplete disclosures feels a little synthetic. Obviously the wording of his first answer to Faisal Islam was imperfect, and it took two attempts by his press office to cover all the hares that had been set running. But it got there in the end.

We have ended up where we usually do after furores of this kind, which is with the demand that politicians should publish their tax returns. The politics of the London mayoralty election in 2012 meant that candidates for that office are now expected to publish – which is why we know about Zac Goldsmith’s fluctuating trust income. At the time, Mr Miliband, Mr Cameron and George Osborne all agreed to publish their tax returns, but somehow never got round to it. If that’s what you want, sign a petition, but be aware that it would make it less and less likely that normal people would ever want to go into public service.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments