It's not shocking that an Oxford University graduate is suing because he didn't get a first class degree – it's inevitable

After tuition fees were brought in, universities became providers of services rather than seats of learning, and students became consumers – we shouldn't be shocked when they act like them

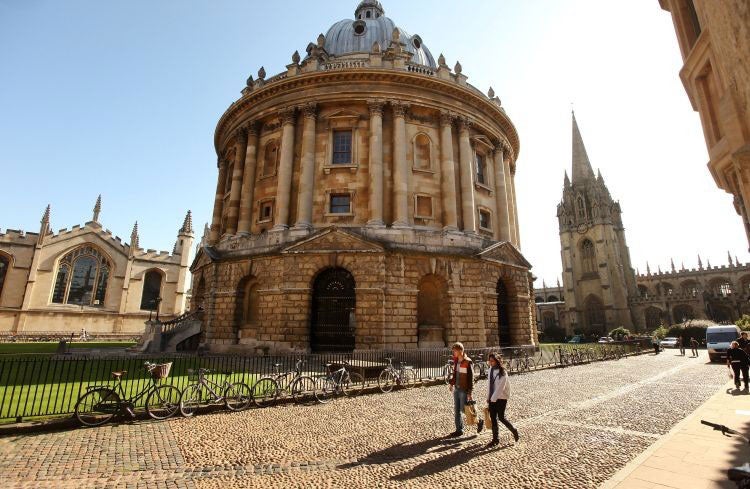

A sweet city, replete with dreaming spires, not needful of June to heighten its beauty: Oxford, as E. M. Forster put it, would much rather have its inmates love it than their fellow inmates. My alma mater, and perhaps Forster too, might be disappointed to hear that that love is found wanting in the case of a former student who has brought a civil suit against the ancient seat of learning for its “negligent” teaching.

Faiz Siddiqui argues that the poor standard of tuition he was subjected to led to him receiving a paltry 2:1 instead of a coveted first class degree. That result in turn, Siddiqui argues, prevented him from pursuing his dream of a career as an international commercial barrister. Years of depression and insomnia (sure sounds like a successful career in law to me) followed. His claim, valued at over £1m, is for loss of earnings.

Many things are troubling about this claim, which, Siddiqui’s lawyers forewarn, is a test case, with a number of other Oxonian alumni waiting to see how it fares. Anyone who has had the privilege to study at either Oxford or Cambridge (or for that matter, anyone who hasn’t) could scarcely help but find a hubris implicit within this legal action that borders on the insulting (to both groups).

The tutorial system of teaching at both universities, which provides students with almost one-on-one tuition with leading experts in their fields, is unrivalled in the world. Not for nothing do Oxbridge graduates continue to swell the ranks of the top jobs in the UK and globally. And, if I might be forgiven for slipping on my own contemptible 2:1 lawyer’s hat for a moment, one wonders how Siddiqui intends to prove causation: that his loss of earnings has been caused by the tuition he claims was negligent, rather than by a personality deficit that’s at least suggested by a burning desire to join the commercial bar.

But while this legal action might be easy to (and worthy of) parody, it is not something that should surprise us. It’s by no small irony that Siddiqui began his studies at Brasenose College around the same time, by my reckoning, that New Labour came to power.

Albeit acting upon a report commissioned by its predecessor Conservative government, it was New Labour that first did away with the idea of higher education being free at the point of use, and not long after pushed through further top-up fees. With further increases in fees made by the coalition government since then, and more expected in the future, it is a consequence, if not the intended purpose, of the changes first introduced by Tony Blair’s government that higher education has been transformed into a market economy.

Universities became not primarily seats of learning, but providers of services. Students were no longer to be academics, but consumers.

Consumers were bestowed not with learning, but with ever-greater choice. And the measure of this new economy became not the elucidation of greater understanding, but the expanding numbers of the population who lined up to consume its products.

Wherever there exists a consumer driven economy, so too there are a collection of rights and expectations the consumer has, which in turn one expects to be protected by the law. As distasteful as it may seem, I anticipate that in the future we will see many more, not fewer, litigious challenges to allegedly sub-standard services provided by our higher education institutions.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to dig out my dog-eared and doodled-upon negligence and contract law textbooks. I too was the innocent victim of some transcendently boring international trade tutorials, which I am sure robbed me of the opportunity (not to mention the slightest desire) to pursue a career in commercial law. You’ll be hearing from my lawyers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks